“The World History of Animation” Book Review

For the animation fan, student, practitioner – in my case, all three – the release of yet another coffee table book on the medium may well provoke duelling feelings of elation and despair. The former as, hey, we all like to geek out over whatever we’re into and, next to DVD boxsets and extortionately-priced figurines, great big books are the way to go; The latter as there can only be so many gigantic, hardcover tomes lined up in a row before our cheap MDF bookshelves start to disconcertingly sag in the middle. Even if you have a bigger apartment and higher quality storage furniture than this reviewer, there still remains the potential for disappointment in cracking open a book you’re excited to own and quickly realising it’s either impenetrably dense, wastefully sparse or simply not that engaging.

For the animation fan, student, practitioner – in my case, all three – the release of yet another coffee table book on the medium may well provoke duelling feelings of elation and despair. The former as, hey, we all like to geek out over whatever we’re into and, next to DVD boxsets and extortionately-priced figurines, great big books are the way to go; The latter as there can only be so many gigantic, hardcover tomes lined up in a row before our cheap MDF bookshelves start to disconcertingly sag in the middle. Even if you have a bigger apartment and higher quality storage furniture than this reviewer, there still remains the potential for disappointment in cracking open a book you’re excited to own and quickly realising it’s either impenetrably dense, wastefully sparse or simply not that engaging.

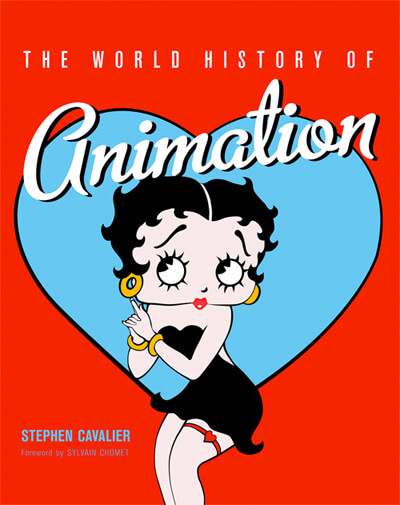

Having been burned in such a manner a fair few consecutive times of late, you can appreciate my relief at discovering none of these issues are a concern with UK-based animator Stephen Cavalier’s “World History of Animation”. In fact, it’s quickly become a fairly hot contender for the most crucial animation history-themed book I own (battling against Jerry Beck’s “Animation Art” and Maureen Furniss’s “Animation Bible”). As its title suggests, the book is an education in the historical sense, rather than the instructional, with no focus on any one specific geographic or technical area of the industry. Its purpose and execution is simple – to lay out and dissect as many crucial turning points, figures, inventions, studios, shorts, features, television shows and all manner of other cultural contributions animation has been perpetuated by. While clarifying early on that, from a researcher’s perspective, the bulk of these have taken place within the US, Cavalier’s decision to interweave these various progressions the world over makes for a fascinating overall analysis of animation’s evolution.

Rather than arrange the book by territory, the best efforts have been made to lay everything out as chronologically as available resources have allowed. This decision serves two fairly crucial purposes – mainly for ease of reference while also telling a more linear story of the development and permutations of the medium, allowing for enlightening examples of parallel thinking, worldwide influences and innovations from animation’s infancy right through to 2010. There is tremendous concession to the uninitiated or casual animation fans, with each concept and development introduced as though they are being divulged for the first time (though this has a tendency to come off as a little condescending). Especially refreshing is Cavalier’s candour and reluctance to romanticise the early years of animation and its pioneers – indeed, the general portrayal is that of an unglamorous industry where ego won over humility, greed over artistic integrity, credit was consistently misplaced and entertainment bled into propaganda. If an animation legend was known to be an insufferable jackass as a person, that side of them is even-handedly documented. Countering LP Hartley’s famous literary proverb “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there”, ours is an industry it seems where everyone’s allegiances and loyalties were just as governed by finances and self-preservation then as they are now. In some cases it’s genuinely sad, especially instances of true innovators such as Georges Méliès and Charles-Emile Reynaud reaching the end of their careers or even lives in relative obscurity. Such engagement as a reader speaks for the book’s virtue as being more than simply a methodical outlying of names, places, dates and film titles – Cavalier clearly cares a great deal for the humanity of the industry as well as the product.

With an introduction by Sylvain Chomet (who shouldn’t need one himself) cheerily extolling the virtues of the book in comparison to the bulk of what’s out there, the main text is divided into four parts. Beginning with animation’s pre-twentieth century origins, followed by the film age (1900-1957), the TV age (1958-1985) and the digital age (1986-now). These are each broken down with spectacular detail, citing nearly (nitpicking to come) every crucial animation milestone over the years. Each is given a fairly brief overview, outlining the essentials and providing enough information for anyone curious to learn more on any given subject for themselves. In some instances the brevity is welcome – the obligatory segments on overdocumented achievements such as “Gertie The Dinosaur” are mercifully succinct and to-the-point – while other, more contemporary endeavours that warrant consideration seem to be merely alluded to. With so much history and territory to cover, I found myself pleasantly surprised at how rarely a name or film wasn’t present in the index. In a lot of respects its voluminousness allows the book to cover territory rarely given the credit it deserves – hidden gems such as Will Vinton’s dark claymation masterpiece “The Adventures of Mark Twain” (1986) and Al Jean’s often-overlooked series “The Critic” (1994-1995) along with numerous other ‘cult’ endeavours are acknowledged for their small-yet-valuable contributions; However for the same reason the omissions are all the more glaring. For starters, not a mention is made of the legendary Warner Bros. “Censored Eleven”, names such as Cordell Barker, Art Davis and Craig McCracken are conspicuous in their absence, as are recent works of cultural significance such as “Madame Tutli-Putli”, a recent Oscar-nominated Canadian film lauded for its pioneering compositing techniques. Nor does Adam Elliot’s spectacular independent feature “Mary and Max”, a tremendous feat for both stop-motion and Australian film – seem to warrant a nod (although to Cavalier’s credit, Elliot’s previous work is given its due). It also seems bizarrely incongruous that a book which acknowledges the important associations between video games and animation – specifically the marketability of the Mario franchise – would completely disregard the work of Doug TenNapel or LucasArts, which embraced the conventions of traditional 2D character animation in video games for the first time, essentially creating the first ‘playable’ cartoons. There are no claims that the book intends to be encyclopaedic and these issues are, I’ll readily admit, the easiest things to quibble about – even a series of books this size would be hard-pressed to cover everyone and everything that fully makes up the mosaic of this industry’s rich, exciting and occasionally troubled history. The concern is less their lack of inclusion as the ephemeral and significantly less consequential work represented in their stead.

Overall though, the presentation, clear writing style and impartial analyses all combine to make it a book that will doubtless become the first point of reference to those who own it. Even after reading it cover to cover, it compels you to dip back into it, which in itself is the quality of this type of book it would be nice to see more often. Highly recommended.

Items mentioned in this article:

![The World History of Animation [Book]](https://www.skwigly.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/The-World-History-of-Animation-book-cover.jpg)