In conversation with Will Anderson about his new film ‘Betty’

UPDATE 25/08/2021 – Will Anderson’s Betty is now available online in full (watch below)

Will Anderson is a longtime favourite of ours here at Skwigly, ever since his directorial debut with his Edinburgh School of Art MA graduation film The Making of Long Bird that enjoyed an extensive festival run picking up multiple awards including both a Scottish BAFTA in 2012 for Animation and a BAFTA in 2013 for Best Animated Short Film. Since then Will has created multiple short films, idents and micro-series for various channels, sites and media outlets, often with his long term creative partner Ainslie Henderson. His previous film Have Heart is a a satirical and deeply moving film about the human condition and feeling trapped by the monotony of life, depicted through the life cycle of a GIF-animated bird plunged into an existential crisis. His new film Betty once again follows a bird-like character – a recurring visual motif in his films – called Bobby, as he searches for his butter, his Betty and ultimately a love that has apparently melted away.

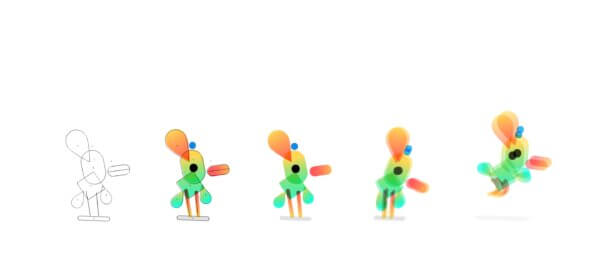

Will’s work often combines meta concepts, naturalistic dialogue, intimate human connection and wit that reflects on both the conventions of filmmaking itself as well as the creative process in general. The self-reflective and jibbing nature of his films speak to audiences, festival-goers and critics alike. His skill as an animator and designer allows him to play with colour, sound and movement to create a minimalist character based largely on contrasting colour and geometric shapes, using elements of glitch art and post-digital storytelling. The end result is a truly modern aesthetic with classic, humourist storytelling full of warmth and genuine connectivity.

Which is quite a wordy way of saying that his new film is truly great! With the film presently screening as part of this year’s digital iteration of the Encounters Film Festival, we were incredibly lucky to get an extensive chunk of time with Will as he wandered the city on his way to work.

We’ve spoken to you a few times in the past, but I realised that we had never asked you about how you and your longtime creative partner Ainslie Henderson met?

We actually met in college, I was the year above him, at the Edinburgh Collage of Art. He was helping me on my grad film The Making of Longbird – he helped write it. During that time, I recorded a ‘job interview’ with him, which became this little short that we made about a Glaswegian seagull trying out for this job. All the direction I gave him was to be this slightly despondent, Glaswegian, happy-go-lucky character, so the dialogue was just improvised. We both found it quite funny, so we started making little things for fun which led to other things. To be honest, it’s still happening, but with more commercial work. Since then we’ve written stuff for BBC with the Pigeons on Tour series and for CBBC which the Scottie Dogs series and then for Adult Swim. It’s kind of always the same setup, Ainslie and I just having a conversation that’s largely improvised. But there’s something about that kind of energy of not knowing where you are, where your endpoint is, but by improvising in-between everything else it keeps it fresh and alive and exciting for us.

What do you think are the benefits of working with someone else in that kind of way?

For me personally, it’s down to individual personalities. I feel it’s so important to work with someone else, just to get their different perspective. I don’t really enjoy it on my own. Making an animation purely singularly I find quite lonely and I really appreciate laughing and having fun coming up with exciting things with someone else. I just think that that’s what it’s all about for me. Obviously, there are times where you work on your own because you have to. It can be a lonely job but trying to be as collaborative as possible helps.

Are you predominately the animator on those short commercial projects?

Yeah, almost entirely. Ainslie has a very different sort of skill set, he’s a stop-frame animator and more of a sculptor. I’m sat behind a computer doing the more technical stuff. The work that we do together, other than those digital shorts, tend to be a mix of stop-frame and digital animation. It broadens what I do and speeds up what he does, so it’s quite a nice symbiotic relationship we have.

Scottie Dogs (CBBC)

A lot of what makes those shorts work is that you two seem to have an effortless chemistry with each other that the audience feeds off.

Yeah, I hope so. It definitely requires editing but I’m glad to hear that that’s how it appears. We are very close friends so there is a sort of spark with the dialogue that would be hard to recreate if we were to get actors. We tend to put ourselves in our work separately as well, so it just kind of makes sense.

Have Heart was your last short film before Betty, was that your first project without Ainsley involved at all?

I would say so yeah, I’d certainly done stuff on my own but not really a full animated short. But we are always involved with each other’s projects in some way, but I suppose with Have Heart it was less. To be honest, it was because he was doing work on his own and I felt than, when you work with someone for a while, you can become semi-dependent on them. I suppose for him, he had just made a film called Stems, which is totally beautiful. And it was him very, very much on his own. I was probably trying to prove to myself that I could work more singularly but he did help out with by giving me some clarity when I was confused about certain things about it.

Have Heart (Dir. Will Anderson)

More like a sounding board?

Yeah exactly! Less with the writing, I guess more just there for perspective but that was the first film for me that I was like, “Okay, I can work on my own”. It’s a pretty personal film as well but I realised that as long as you’re honest and opening up about something that’s personal to you, people will listen and hopefully enjoy it.

So Have Heart was based on a GIF at first and you did it whilst you were like commuting at the time?

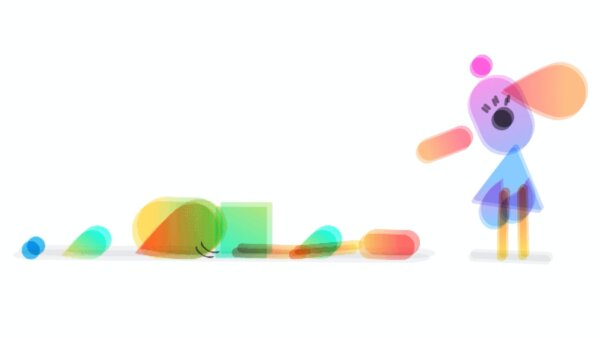

Yes, as freelance animators, we tend to make things the satisfy us and post them online, hoping for appraisal or that people see and like it. I was thinking about that when I was making this thing and how just social media, in general, is this constant clamoring for attention, it’s kind of an ugly thing but also what we have to do. It’s sort of an unsettling feeling, so the GIF itself refers to that a little bit, the idea of trying and failing and trying and failing. Then having this thing that existed in the world on a timeline, I started to think about how I could develop it. I saw the rule – because I think it’s important to have very strict rules to make work and tell stories – as “I’m going to just move chronologically from here and see where we end up”. It was almost like an experiment to see how far I could take this little collection of shapes and where they would end up in the course of around a year.

During this time, I was working a lot at a design company in Glasgow and commuting a lot from Edinburgh. So, I was finding that there were two hours a day which was a good opportunity for me to work on personal projects. The more I improvised as I was going along, the more responsible I felt for the character that was starting to think and do things and make decisions. You start feeling this sense of responsibility to guide this character through to the end and see where it takes him or her and yourself. It’s like going on a journey with them, if that makes sense, which potentially sounds a little bit pretentious, but it really is genuine; it’s just another way of improvising, like acting, I guess. You find out more about yourself and you know your ideas by making it up as you go along.

I think it’s interesting because it’s more naturalistic, it’s how you think people make films when you’re younger, that they’re made up as they go along, playing about with ideas and just having things happen.

Yeah, I love the idea that like we get to play, that’s a good way of putting it. I think everyone expects to know exactly what they’re doing and have all this insider knowledge of how we make work and how important our ideas are. I think people who make films that way are fantastic but I also think that if I was to do it that way, it would seem very stiff and unnatural. So, I look for a way that I can speak as openly and freely as possible. I just find that’s a much more honest way of working.

All of those things are very much reflected in the film and I think it’s one of those difficult things when it comes to animation as an art form, that it is a highly structured thing as often many people have to work together. However, the animation itself is an individual pursuit if you’re not working with anyone and can be more self-reflective.

Absolutely, I completely agree. I’d say it’s also with films like Have Heart where there are no storyboards, no animatic, none of that. That would totally kill it for me, I think. It’s the same with the new film, Betty. It’s about discovering something and getting somewhere that I would never get any other way without improvising. It’s much more about exploring thoughts and feelings and emotions than knowing exactly what was happening.

Have Heart (Dir. Will Anderson)

I think that’s the strength in all of the films that you’ve been involved with. You can really feel your mental state and how important self-reflection is both as a filmmaker, but also to represent to the audience about filmmaking. Do you think this is a recurring feature of your work?

Yeah, I think so. I’m glad you realise that. I go a little mad unless I have something creative ticking over in the background. It keeps me sane because I’m just one of those people that gets very, very anxious when I’ve got nothing to do. So with the most recent film I had just come out of a relationship and something didn’t quite make sense about it all ending. I kind of needed this project on the side so I could make sense of it. I was feeling stuff that was evaporating into the atmosphere and not going anywhere, so I wanted it to go somewhere useful instead of just disappearing. So in that way I wrote this fictional thing, that’s what Betty was for.

Betty (Dir. Will Anderson)

The fictional element of it is a mixture of The Making of Longbird, the first film I made, and Have Heart, the more recent one – it’s pretty much a mix of the both of them. You follow these characters, who have their wants and needs and they’re going on a little journey, but then there’s this other element below the surface. There’s another layer, a non-fictional element, which is my voiceover almost like a director’s commentary but it can be turned on at any point, mixing those fictional and non-fictional elements. I don’t want to give away too much, but I was interested in how that gets disrupted and how those things overlap, because you come with expectations too. You’re sitting down and watching a film, then suddenly everything turns and you hear this booming voice from whoever, the director or producer, and there’s a completely other set of expectations for what experience you’re going to go through with that. I was interested in that because, for me, filmmaking is a very personal thing so it makes sense that I can just talk over and speak to people directly.

Have Heart had that element of being quite reflective, but with Betty I was getting worried that I was getting too ‘film clever’ about this. I started to think maybe I should go back a step and just continue talking about what it is and just admit what I was doing and not dress it up.

Your previous films have a meta feeling with self-aware characters and playing with the audience’s perception but with, as you said, a more truthful reveal. However, in Betty, the character isn’t aware of you as they have been in previous films?

Yeah, that’s true as well. I’m realising that now, they are separate.

If you think of your three films The Making of Longbird, Have Heart and now Betty, in Longbird the character is almost bullying you, in Have Heart you’re almost bullying the character and now in Betty Bobby exists more as a way for you to explore your feelings?

Yeah, you’re absolutely right. Again, some of this is working on a subconscious level. I don’t break down absolutely every decision that’s made, obviously, but lots of them are. So you’re totally right because I’ve voiced the character as well, but he is a separate being. It’s funny because it’s almost like a relationship where you only hear from one point of view. Bobby’s voice, just this American guy which is my voice pitch-shifted, was part of the real relationship in the real world. We gave our egos these American voices and if we got pissed off at each other, we could be these Americans. We wouldn’t be annoyed at the real us, we’d be annoyed at these fictional versions of us. The character Bobby in the film is that guy. He’s not me. He’s this American, same with Betty. So they’re a version of this other version of us.

It’s hard for me to talk about because, having some experience of making films over the last few years and playing at festivals, I feel like it takes a little while for me to know exactly how to talk about a film because I can gauge people’s reactions at festivals or in reviews and then start to get ready to talk about the film. At this point right now it’s a really strange, vulnerable time because I haven’t seen enough reactions to it. For me, I just needed to do it to process a thing that was happening in my life, it felt kind of pathetic. It’s quite a pathetic thing feeling heartbroken over someone, everyone will have felt that in some way but I needed to put it somewhere.

‘Pathetic’ strikes me as an aggressive word to use on yourself, especially for something that is both very human and also something that everyone feels at some point.

Yeah, I think it’s just because I’m referring to myself. I don’t really like showing weakness, I don’t want to be like a victim or anything like that. So I’m careful about that and with a thing like heartbreak, I realised my gut reaction is to say someone wrote a song about it and there are loads of them then there’s a part of me that feels a little uneasy. For myself, I wonder if it’s really worth making a film about it and I don’t know if I buy into it, but actually it’s a pretty universal thing. It’s like falling in love, everyone’s done that – or most people have, or think they have. It was the same with Have Heart, everyone feels stuck in a rut at some point. Everyone has an existential crisis, and Longbird is about struggling with your ideas and feeling like they’re stupid. They’re all thematically linked. They’re quite human.

Betty (Dir. Will Anderson)

In the end I genuinely felt that it helped. There’s something about making animation that, although it is obviously my job and I do enjoy being a creative doing creative stuff, there is something just fundamentally quite stiff and false about it when you say you’re going to tell a love story in this medium. It’s challenging, I would struggle to do it with a script and getting actors in. If it was funded and there was a crew that were waiting for me to decide how I’m feeling that day it wouldn’t really work.

So, do you feel like it’s almost more like a diary?

Yeah, it’s like opening your sketchbook I think – and it’s terrifying opening your sketchbook and letting someone just peruse through and read it and make it public. I suppose it’s my job to be the author of it and direct the viewer and that’s why in these films – Longbird, Have Heart and Betty – it’s my job to clean up all the mess around and make it as tight and focused as possible. So, someone I don’t know can look at it and hopefully be entertained by it.

Something that I’ve noticed, probably since Have Heart, the MTV ident and the Best Friend series is that there’s a visual style change that incorporates a form of glitch art and post-digital art filmmaking…

Yeah, I think it’s a way of doing new things. So, with Adult Swim we were doing something a lot faster. When it’s a new piece of work you rewrite and build it in a way that’s faster which is often to do with the brief, but with the speed came more energy. With the MTV ident, specifically, it’s a 15 second sequence with no dialogue and, as you know, we do dialogue all the time. We cut that out so there are loads of characters at this rave which has this sort of hysteria about it. It created this chaotic energy which I’d been wanting to experiment with for a while, this kind of live puppeteering idea, but had never had an excuse or the right thing to try it out.

This was perfect because I could do all the animation in basically a day. It requires rigging and setting things up, but it was a great opportunity for me to just try something out and for it to have an audience. So that’s why it looks the way it does. Everything’s perhaps a little rougher with the arms, and all the joints don’t quite meet but that fed into the idea and it’s important that visuals and themes are somehow linked to the form of the medium that you use. That always just makes sense to me, like with Long Bird he is a silhouette because he’s been cut out, and with Have Heart he’s just a collection of shapes that have been thrown together that are constantly falling apart. In Betty, Bobby is a little love bird who’s just created to keep a relationship together. The form is always somewhat linked to the theme of whatever is being talked about.

Yeah, of course, it’s a good way of working. Glitch Art is both a visual thing and a narrative form, which has become more prevalent in filmmaking since films like Ugly which broke the rigging and used that meta concept to represent how audiences are becoming a lot more intelligent to what the process of making these things are.

Yeah, absolutely. I suppose with Ends you don’t know if they’re going to die or come back, so the glitching made sense by tying it in somehow to the idea. But also you’re completely right, there is a visual language that exists that people are aware that animation is made, created and anguished over. People understand there’s a tension between what they’re seeing as being this completely fabricated thing and what’s real about it and I like that tension with dialogue. What we tried to do is naturalistic which is at odds with what animation is. It’s all about that tension. I think.

I think what’s quite interesting about that with Betty as well, is that you’re not really talking at the character and Bobby is talking to Betty, but Betty doesn’t speak. ever.

I thought she was a really important character in the beginning when I was improvising. Then I realised that in fact, it’s really about her not being there. At the start of any film, there’s this normality, then there’s usually some kind of disruption and then you go on a journey to try and fix that thing that broke the normality. Then at the end you get to a place that hopefully shows a perspective you hadn’t seen before. That’s perhaps better or worse or different from where we were, that’s what that journey is for me. I don’t know where it’s going to end but it’s going to end somewhere and I’m just yearning to find out what it will be.

In Have Heart I didn’t know the ending until three-quarters of the way through making it, but with Betty it was even closer to the end; where it stops was me making a call saying “This is okay, this is satisfying for me”. God knows if it is for anyone else! But it definitely was a little eureka moment, where you go “That’s totally what I was looking for and it was staring me in the face”. I’m actively trying to do it with as little as possible as well, I like that there’s clarity and simple bold shapes, geometry and minimal dialogue with Betty, as with Have Heart, the simpler it is, the more beautiful I find it. There’s a symbolic moment where he keeps losing his butter and it’s just silly, it keeps turning off and on and he’s tied to the fridge and that becomes representative of him trying to look for signs he can’t quite grasp, which is a metaphor for his relationship. I suppose that there’s some kind of method in telling the story, something that’s really hard to talk about – “How do I get over someone? How do I find love?” But I think in the film, it makes sense, this symbol of him trying to try to hold on to something.

You can see more of Will Anderson’s work at wanderson.co.uk

Learn more about the making of Betty in episode 2 (season 4) of Intimate Animation (stream below or direct download)