An interview with Cartoon Saloon’s Tomm Moore, director of ‘Song of the Sea’

Tomm Moore

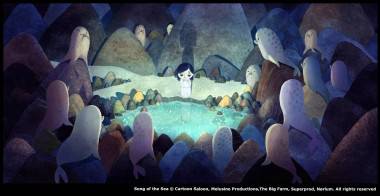

Directed by Tomm Moore, Song of the Sea is the latest feature film by Cartoon Saloon. A powerful story about a family’s struggle to stay together after the children’s mother disappears, Ben and Saoirse must adventure through the world of the Irish faeries to return to their father and save Saoirse from peril. Tomm, based in Kilkenny, Ireland, founded Cartoon Saloon in 1999 alongside Paul Young and Nora Twomey. Amongst the studio’s various projects, which include the short films The Ledge End of Phil (from accounting) and Old Fangs as well as the TV series Skunk FU! and Puffin Rock, Cartoon Saloon’s recent major focuses have been on feature films, beginning with The Secret of Kells in 2009. Skwigly had the pleasure of catching up with Tomm ahead of the UK cinema release on July 10th.

Can you tell me a little about the inspiration behind the film?

It’s kind of a spiritual follow up to Secret of Kells in a sense, but for me it was an attempt to sort-of re-imagine some of the old folklore and re-tell it for a new audience, a young audience, so that the folktales and folklore that inspired it didn’t become considered by kids to be passé. I wanted to try and reinvent it for the vernacular of today, you know?

Absolutely! Was there anything that you picked up from making Secret of Kells that helped you with Song of the Sea? Was there anything that you learned in that process?

I was eager to apply as much as I could of what I learned on Secret of Kells for Song of the Sea, but there was a five-year gap between them, so things change, even technology. We ended up animating Song of the Sea with TVPaint, which I was a bit reluctant to do at first because we’d been very much a pencil-and-paper studio for a long time. I finally converted and I’m glad I did, because I think it allowed us an efficiency to be more creative and I think maybe do better animation.

I suppose Song of the Sea is almost a spiritual following of Secret of Kells in terms of its style as well?

We wondered, “should we do something very different?”, because we evolved the Kells style very purposefully to emulate medieval art or stained glass windows or illuminated manuscripts, things like that. It had become ‘my style’ as it were, kind of my first instinct. So what I did was I asked Adrien Merigeau, who was one of the main background artists on Kells, to be the art director. Between the two of us we kind of matched our styles and I think we found something that was a nice evolution. Watercolours just felt like the obvious medium for Song of the Sea – he’s such a talented watercolour painter, I learned so much from him and he brought some really interesting influences.

It suits the fairytale theme really well. Were there any challenges in using that 2D style?

Not once we committed, but at the start there were discussions with different bigger entities that would have wanted it CG or whatever, but that wouldn’t have been the main problem for me. Going that route would also have meant that not only would you have to go CG but you would also have to make the story much more commercial, more like in the general style of modern CG animated films. I think 2D animation has a timelessness.

I really was interested in making a stereoscopic 3D and we did a test with 2D illustrations but with stereoscopic 3D that looked really cool, like a pop-up or something, but in fact the co-producers pushed back against that. It would have been so much more expensive. They were probably right!

There’s a really strong moral behind the story – the environmental message. Do you feel that it’s not just about keeping fairytales alive and relevant for children, it’s also about giving them that message?

Yeah, the story itself came from a trip in the west when my son was about ten. We came across a seal cull where the fishermen had started to kill the seals out of frustration, I suppose. The lady that we were renting the cottage from was telling us about how the old folk belief would have linked people to the environment much more so they would have been more respectful, at least of seals. It was a folk belief that people were losing touch with and were getting more and more embroiled in this kind-of ‘celtic tiger’ thing that was happening in the country at the time, where we must profit before anything else. So I sort of wanted to wake people up to that kind of wisdom that was already in the culture and remind them of that. I’m glad the environmental angle is still there in the film.

Do you think animation brings something that live-action can’t, where you can talk about more serious subjects with more nuance perhaps?

Yeah, we talked about that a lot. We talked about it on Secret of Kells as well because there’s some pretty heavy esoteric ideas floating around there. Even the history, the time we were dealing with all the vikings and stuff, made us question how heavy we wanted to go. When you look at movies like The Grave of the Fireflies by Takahata, I think animation has an interesting quality where you can make things bearable that might be a bit melodramatic or too much in live-action. At the same time they’re more immersive in a way, you can relate more with the animated characters because they don’t seem so different. Somehow animation has the power – at least for me when I was young – that I got more sucked into the story.

Concept art by Adrien Merigeau

Can you talk about some of the other fairytales that you used for Song of the Sea? The Great Seanachai, the fairies…

We had too much in the first draft, so we kind-of pared it back to just the folktales that we could adapt to mirror what was going on with the family. The central thing was that we felt that the selkie stories generally were about dealing with loss; they always dealt with the selkie returning to the sea and leaving their family behind, so we thought Okay, that’s the theme, that’s the key story, we’re dealing with a modern family dealing with loss and how broken it is.

The Great Seanachai is almost an homage to Eddie Lenihan, who would have been on TV when I was a kid with the Ten Minute Tales and he was amazing. He’s an amazing guy, he keeps the stories alive in the oral tradition. He’s got this amazing big beard, so we had some fun with the idea that each beard hair might hold a story. Mac Lir was obviously so we could mirror Connor. Mac Lir was the son of the sea, the sea god, and there are some sad stories about Mac Lir in Ireland, and even the Isle of Man has a certain connection with Mac Lir. Eddie always says that the folklore and fairytales are not gospel, they’re not written down not to be changed; he adapts them every time he tells them and, because they’re an oral tradition, they evolve for every audience and every generation that tells them. That’s how you keep them alive.

What else are you working on currently?

I’m personally engaged in developing my next feature called The Wolf Walkers. That’s sort of what I’m working on day-by-day now with Ross Stewart who was the art director on Secret of Kells. We co-directed a little chapter of The Prophet for Salma Hayek’s company last year, that’s being released this year, and so we’re trying to do our first feature together as co-directors so that’s going to be fun.

That’s very exciting! Have you had much of a reaction yet from The Prophet?

Yeah, I’ve only heard good things. I was excited to see it myself! The story that I always tell about The Prophet was that when I was in school I never got picked to be on any teams or anything like that so when they called me up and asked me to be on a team with all these amazing people like Roger Allers, Bill Plympton, Nina Paley and the Brizzi brothers, I was like God, I have to be on that team! So even though I was very busy, I found a way to make time to work on that as well because I just think it’s an amazing collection of artists they put together for that project.

Song of the Sea opens in UK cinemas this Friday, July 10th. You can hear more insight into the making of the film from director Tomm Moore in episode 30 of the Skwigly Podcast, which will be released this Monday.