‘To Boldly Go…’ London International Animation Festival 2019 Review

‘To boldly go…’ The ambitiously titled Opening Gala at London International Animation Festival (LIAF) this year offered a promising selection of Sci-Fi shorts, each directed by female animators. The films were determined to throw a curve ball into the popular genre, often defined by themes of masculinity and conquest. Animate Project’s Abigail Addison curated the programme, showcasing a multitude of hypothetical futures. Some were dystopic, others deeply satirical, and some involved a passionate love affair between a woman and a 3D printed slug.

This was the case for Sophie Koko Gate’s Slug Life. Fans of Koko Gate will recognize her trademark style of sweaty, fleshy, oozing animation. The film followed a day in the life of Tanya as she artificially created her perfect slug companion. The short was dripping with seduction and mucus, yet it was not the only film to exhibit grotesque themes. In the discussion which followed, this was deconstructed by visual artist, Katerina Athanasopoulou, who related the attraction to the grotesque to an embracing of the alien and unknown. That which could be termed ‘other’ or ‘monstrous’ is reclaimed and celebrated when Tanya locks tongues with her illustrious slug or the characters of Flóra Anna Buda’s Entropia shop for crunchy maggots at the supermarket. This is quite a departure from your average shoot em up’ style Sci-Fi film. The filmmakers procure an interest in the strange or gross rather than reacting with abject fear or hostility.

Flóra Anna Buda was also present during the post-screening conversation, as was Chiara Sgatti with her film, The Thing I Left Behind and academic Lilly Husbands. Buda may be one to watch for future creations, having picked up a Teddy Award at Berlinale earlier this year for her graduation film. Additionally, she had a hand in the making of Nadja Andrasev’s Symbiosis which featured later on into LIAF’s selection.

Also featured in the Opening Gala,The Law of Celly, directed by Mariola Brillowska was distinct as a foreboding portent for an automated world. In Brillowska’s version of a not-so-distant future, the viewer is taken on a nauseating journey. The narrator describes the doctrine of a nation which makes it an imperative to own a mobile phone. In this way, the government is able to harbor the data of the unemployed for ‘embedded in this device are sensors which monitor bodily functions.’. Even the passing of urine can be monetized in this perverse reality. Brillowska’s provides her hyper-cynical commentary to a civilization which has carelessly discarded freedom and human rights. This film really has to be seen to be believed. Brillowska’s use of bright and garish colours conceals the incredibly bleak message at its core. The animation style is somewhat crude, yet the originality of its idea wins out, as was the key to other films in the selection, depicting the alarming advancement of technology and the horrors that may wait.

Elsewhere in LIAF’s programme, audience members enjoyed the rich visual languages made possible through animated film. Jiaqi Wang’s short 2.3 x 2.6 x 3.2 portrayed the experiences of a young boy with a tumor of these exact dimensions. The film appeared to be made up of flickering lino-cut prints. This technique is not widely pursued for obvious reasons. However, the textures of the print were perfectly akin to the visceral tone of the film – the boy’s exploration of his own anatomy and the uncertainty of his disease.

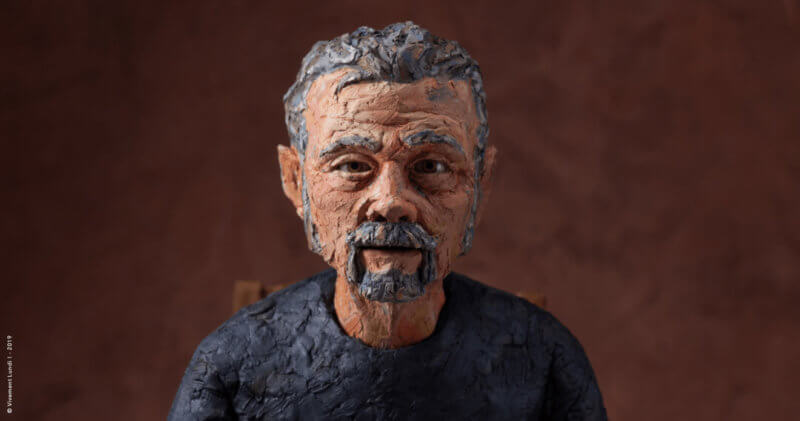

Perhaps it is when form meets subject that we are most inclined to let a film settle in our memory. The coincidentally titled Mémorable (see our interview with Bruno Collet) was another film which stole hearts at this year’s LIAF. Screened among the ‘Playing with Emotion’ selection, the stop-motion film adopted a painterly style. It follows Louis, a retired artist, and his wife. Through the eyes of Louis, characters and objects begin to mutate. A phone dissolves into marbled plasticine and friends at a dinner party come to resemble Francis Bacon portraits. Altogether, the changes that occur in Louis’ world are consummated as a subtle and poignant rendering of the effects of dementia, (though this is never plainly stated.)

The films succeeds, overwhelmingly, due to its marriage of style and substance. The rippling, merging plasticine is a perfect visual analogy of Louis’ degenerating world. Louis and his wife struggle to connect as reality becomes abstract, separated and fluid.