Theodore Ushev on ‘Sonámbulo’ & ‘Blood Manifesto’

Following on from his thought-provoking 20th Century Trilogy, experimental animator and multimedia artist Theodore Ushev has remained busy. On top of producing art installations and contributing to Anca Damian’s feature film The Magic Mountain, the Montreal-based, Bulgaria-born director returns this year with two spectacular new – and curiously disparate – short films, both of which are screening at festivals throughout the world including OIAF and Encounters this week alone. In the self-penned animated poem Blood Manifesto Ushev continues his tradition of marrying stunning abstract visualisations (rendered, in this case, using real blood) with stark, on-point sociopolitical commentary. Sonámbulo, meanwhile, takes the audience on an entirely different journey of music, romance and artistic celebration. Skwigly are delighted to catch up with Theodore Ushev and learn how these latest additions to his acclaimed filmography came to be.

The opening shot of Blood Manifesto certainly pulls no punches, and the implication is certainly that the film is animated in real blood. Is this the case?

Yes, the film was animated with my own blood. I tried different kinds of blood initially (let the rumours start here, but I’m telling you, your imagination is not good enough to guess everything), and in the final cut there are still some parts from this initial [experiment with] different bloods.

Then as the text became more and more personal, I decided that it had to be my own blood. The opening shot just shows my first attempt to slightly scratch my hand and get some samples. Then I got the idea of using a laboratory, and I donated some blood (my sister, a laboratory technician helped me with this). Then I took some conserved blood—50 ml to be exact.

Since I used it for drawing on small pieces of paper, I used only 25 ml. The most difficult part was getting a contraband, bio-based product through customs. If the officers caught me, I could be in real trouble. I can just imagine the conversations and reactions there: “Your own blood? To paint with? A film?”

Can you elaborate on the NFB’s Naked Island Sessions project, to which this film belongs? Are there parameters that helped shape the final film?

No precise parameters were given to us. It had to be about the lonely voices on the lonely island, commenting on the world over there—and the world is in a pretty depressing state.

What motivated such a stark, aggressive approach to the animation?

It was my cry. For not being able to change things. I watched some students on the streets, rioting against corrupt and selfish governments. The police beat them. There was blood on their faces. Blood spilled for nothing. Nothing changed afterward. The same bastards and pigs running the world, no matter how many rivers of human blood are running on the streets.

For the benefit of those who’ve not yet seen it, how would you summarise the meaning of the poem and, by extension, the visuals themselves?

What is the spilling of our own blood and physical sacrifice worth? What can ideals bring us? How far should we go in defending them? How can an individual change the constant human impulse toward chaos and war?

Although the film has a particular uniqueness to it, the themes and flow of imagery are reminiscent at times of your 20th-century trilogy. Artistically speaking, would you consider this film an extension of those or a departure?

I don’t think there is a connection between them. But yes, if Gloria Victoria predicted the war (If you watch it now, you can see everything: How the war started, the refugees’ crisis, even how it will end) Blood Manifesto takes it from there. Now it’s the individual’s turn to try to change this destructive tsunami. How? Should we flow into the streets, start a revolution and lose our individuality again, turning our blood into a flowing blood river? It is a film about the individual and society.

There is also another difference between Blood Manifesto and the trilogy. It is my first film without any music. There’s only my voice (and my whistling at the end).

Does the tune whistled over the end credits hold any special significance?

Of course. It is La Marseillaise, the song of the French Revolution, the first-ever bourgeois revolution in the world. It connects with the appeal to revolt, to change the system.

Another new film of yours Sonámbulo seems, by contrast, to be a somewhat lighter affair. From where did this project originate?

It started a long time ago as a side project to my heavy, politically charged films. I even don’t remember making it. Every artist needs a vacation from the crazy world around them. It is my healthy dose of dreams and sleep. My mother said I used to be a sleepwalker as a child. So, I maybe drew the film while sleeping. On the other side, my initial inspiration came from the F.G. Lorca poem Romance Sonámbulo.

Both films take poetry as a source of inspiration. While Blood, I believe, was written by you can you describe your process for visually interpreting Lorca’s Romance Sonámbulo?

My goal was to transfer the words to a kind of visual poetry. For me the poetry is pretty powerful in its own right and very often collides with the images, when combined with animation. So, instead of using words, I decided that I’d use Kottarashky’s music to bring me closer to the creation of a surrealistic world.

The images go by at a speed that makes it hard to quite pinpoint the exact method of execution for the animation itself. Can you elaborate on how the visuals were created?

Pure animation. It is a return to the forms and the happiness of the pure animation of the early days, as it was in the early works of the Fleischer brothers and McLaren, etc. It was clean of tedious stories, constructions, and texts. You know, the attempt for “pure cinema” that Bresson, Vertov and many others nailed in the last century? This is what I think I’m trying to achieve with Sonámbulo—a revival of the form, the pure pleasure of the movement itself. L’animation pure is my goal, and I hope I can bring the form to a clean execution one day.

Was the music track by Kottarashky a pre-existing piece or was it written specifically for the film?

Pre-existing. Some changes were made after though.

The film is described as ‘a surrealist journey’—are there any particular surrealist artists from whom you’ve taken inspiration?

Every significant surrealist author participates with one character that appears for a while and transforms into a character of mine. That was my little post-modern game that I played with the spectator.

In what ways does producing work for/with Bonobostudio differ from doing so with the NFB?

The film was not produced by Bonobo; they are only distributing it (although, I really want to work with them one day, ’cause Vanja and Mirna are just amazing professionals).

The film was produced by Dominique and Galilé from L’Unité centrale, with the support of CALQ [Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec] and the Canada Arts Council. The difference? There was no difference in artistic freedom. But it seems that when I work outside of the NFB, I feel less pressure to make a “successful” film. You know, the NFB is a publicly-funded organisation, and I kind of feel obliged to give the best of myself, to use every possible way, colleague or source out there, so I can make the best film that will be a festival favorite. When I work independently, psychologically I don’t feel that pressure, and that gives more unpredictable, unpolished—selfish, if you want—works. I love the two processes.

I wouldn’t be able to make the films that I do at the NFB [without them]—this is the best place to make films. With all the professionals there, films get really polished. So sometimes the rebellious artist in me needs some chaos and anarchy that can purely satisfy the creation of some raw art that doesn’t have to be justified. Making films outside of the NFB also helps me to reach some interesting small festivals and markets that the NFB is usually not attracted by. I think that from the marketing point of view, there are some really interesting options that are worth taking the highest-risk approach for. Obviously, being at such a huge and financially accountable organization as the NFB, we wouldn’t be able to try the free fall [approach]. So I try this outside, and if it works, it serves the NFB after. It is a win-win process. The only loser can be me, which is perfectly OK.

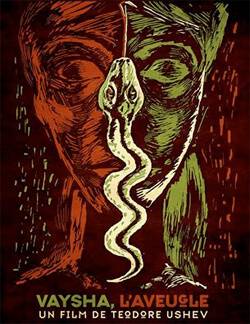

Can you tell us anything about your upcoming project Vaysha, l’aveugle?

I really hate talking about upcoming films. The only thing I can say is—just watch out. It has many things that I have never done before: technically, artistically and in terms of storytelling. [It will be ready] shortly. I’ve never been so excited before.

Sonámbulo is playing at Bristol’s Encounters festival today in the Sensual Delights screening at 2pm, while Blood Manifesto can be seen 2pm Thursday as part of the Close to the Edge screening and again as part of Saturday’s Animation Highlights (12:30pm). Other upcoming screenings include the Ottawa International Animation Festival and Vancouver International Film Festival in Canada. For more info on Theodore Ushev’s work you can visit his official site. To watch/purchase his previous films check out his NFB fimography page. You can also follow him on Twitter.