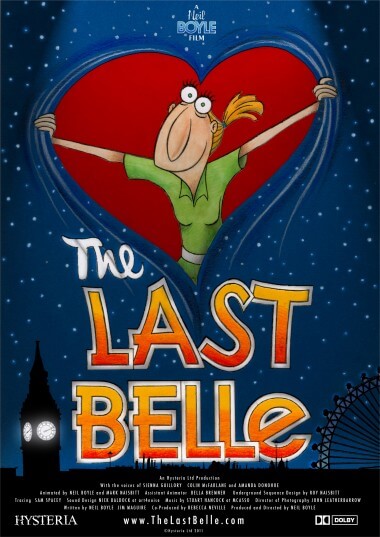

Neil Boyle On “The Last Belle” – The Last Cel Animated Film?

It would seem that the technology that helps put together a traditional 2D animated film progresses on an almost daily basis. In the past decade pens and paper have been slowly replaced in both the pre-production and production stages by Wacom tablets and vector based graphics software that seems to need updating as soon as you have learnt it. The days of white gloved assistants carefully dobbing paint onto the back of an expertly produced animation cels seem long gone in our computer led world. The only place you are likely to find a recently produced animation cell would be in the Disneyland gift shop or online as the “perfect gift” for animation enthusiasts to place in their studies like fossils. A reminder of a forgotten age.

That is unless you take a trip to the studio of Neil Boyle. His latest project “The Last Belle” is a project 15 years in the making which has passed up on the option to create 2D animation on the computer and instead has sharpened a blue pencil, opened up a fresh pot of ink and donned the white gloves to paint thousands of animation cells to create the short. What’s remarkable about this film is that the director and his crew have not only managed to create a film and overcome all the technical obstacles the industry faced before the widespread use of digital painting software, they have also managed to create a kind of quality rarely seen in animation nowadays. The technique is not the only commendable thing about this film. This film – like any film – could easily have been terrible if the animation had been poorer or the pacing terrible, but its not. Its hardly surprising when you hear that most of the crew who worked on the film also worked on Richard Williams on “The Thief and the Cobbler” (the good stuff from it, not the stuff that was shipped in from overseas) Its clear from the character animation and the quality of the performances that you are watching something special created by people who know exactly what they are doing.

Director Neil Boyle preparing a cel for film

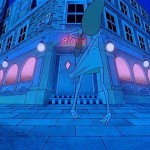

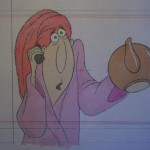

The story centers around a blind date. Rosie has a date with Wally who has promised in his emails to her that he is London’s answer to Brad Pitt. In actual fact he is a beer-drinking slob, who’s beer swilling, takeaway and dirty video indulging lifestyle would be called excessive even by the cast of “Men Behaving Badly”. As the date draws closer they both find themselves on journeys, Rosie towards true love and Wally on a beer fuelled mad dash that takes him on a rollercoaster of comic misfortune through London’s underground and beyond in a race against time to meet his date.

This film is loaded with charm. it could easily put you in mind of the kind of work the BBC or Channel Four used to commission to sit snuggly in their Christmas schedules, its the right length, its bold and bright without any harmful dialogue or the kind of explicit scenes that may put you off your Christmas dinner and its packed with slapstick laughs that would entertain anyone in the family. The film has a real identity as it is set in gloomy London which is expertly caricatured with its crammed tubes, grotty weather and dreary offices that will be familiar to any visitor or resident.

Neil Boyle has created a wonderful film that entertains thoroughly as well as leaving a more appreciative audience with a reminder of what the craft of animation can achieve in terms of both film making accomplishment and technical perseverance.

You can see more of the production in our gallery below or by visiting the Last Belle blog by clicking here

We were glad to take the time to catch up with Neil so he could explain how the film was made and how his background in the industry helped shape the film.

How did you get started in animation?

I left college in 1987 with my friend James Baxter, who is a big name in America now, before then the two of us started together working on films. We then heard about a production starting called “Who Framed Roger Rabbit” in London. So we ran, I mean literally ran, like maniacs with our little bit of film and got hired as inbetweeners. So that was the beginning of my career really with this incredibly lucky early break to be working with big names such as Bob Zemekis, Stephen Speilberg and Richard Williams. By another tricky fluke after the four week trial period I was hired as Richard Williams assistant animator. Whilst James went to work as Andreas Dejas assistant. That began my quite long association of working with Richard Williams. It was kind of scary, I went up to meet him when he gave me some work, I was very professional but as soon as I left and got back to my desk I sat there shaking for an hour thinking “My God how am I going to do this work for the amazing Richard Williams”, after literally falling out of college, so I worked very long hours through lunches and evenings. I would then bring the work in casually as if I had just completed it when I had actually worked 16 hours to get it right. It was an amazing lucky break.

What was Richard Williams like to work with?

I find him possibly the easiest director I have ever worked with in many ways, he is very demanding in terms of quality of work and the speed that you do it, but as long as you do that you are alright. He is a very clear director. He is very precise about what he wants to see. In that way I find him very easy to work with and also he is an incredibly generous guy with the information he has at his disposal from working with people like Milt Kahl and Ken Harris if I was interested in anything at all he would just down tools and explain it.

Did you assist him on “The Thief and the Cobbler” as well.

Once “Roger Rabbit” finished I collapsed from exhaustion for three months before eventually springing back up again to begin work on “The Thief and the Cobbler”. He started me off on fairly simple scenes. People who do not know much about The Thief and the Cobbler, it was a film that went on for years and a lot of the legendary Hollywood animators worked on it doing rough animation but non of it was ever cleaned up or in colour so you could find yourself cleaning up for Ken Harris or Corney Cole. Sometimes you would need to add a little more to the animation and play around with ideas to blend your own animation back into Kens before getting them cleaned up.

The Last Belle is created entirely traditionally

So you could actually say you worked with Ken Harris!

I worked with him vicariously, although I never met him. I don’t want to sound sentimental, but its such a precious relationship and although I never met him there is not a day that goes by in my working life that I do not apply the things I learnt from working with Ken Harris. You would open up a box of his artwork and break it down and try figure out how he came up with the stuff and try understand how he arrived at the decisions. As I began trying to match his style, in a way, I got into his brain and had a year and a half working on his stuff. He was just an amazing teacher and even though I didn’t meet him, and he didn’t even know I existed everyday I use what I learned from him. I do not believe in an afterlife but if I am wrong and I go up there the first hand I am going to shake is his and just say thank you!

Like “The Thief” your film “The Last Belle” took a long time to complete. How did the finish product differ from the original idea after such a long time in production?

A lot of people who ask me about working on this film ask how I can work on something for so long and not get bored. I have a very particular way of filmmaking by working with the script first. trying not to get too visual first. An animators disease is to love visuals and fall in love with your own drawings. What I really wanted to do was nail the story, although I am not making great claims to storytelling, it is a fairly simple, fun, cartoon story but I really wanted to get that script right. In the end we did about 27 drafts. I worked on it alone before getting my friend Jim Maguire to help as well. The way I kept it interesting for myself was by following a structure but without adding detail, like the underground sequence – that was not planned in the script. That way I could keep it alive for myself by adding bits as I went along. I managed to keep my own interest for 15 years working that way!

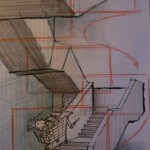

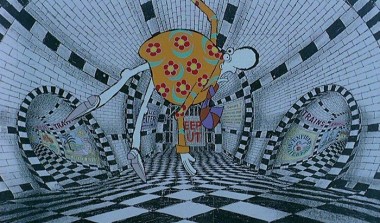

Layout legend, Roy Naisbitt works on the films spectacular underground sequence

That underground sequence was fantastic, you worked with Roy Naisbitt on that, how does he create such wonderful imagery?

I have worked with Roy off and on over the years and I knew his work from the Christmas Carol film that won the

Oscar for Richard Williams. Roy has a very distinctive way of using perspective. Its very dreamlike and very distorted – almost fisheye, I can’t put it into words really its very unique. When I came up with the script with the drunk guy I thought that the strange perspective fits the feeling of drunkenness, with the room spinning around you and the floor not quite being where it should be (speaking from personal experience!) I though Roy was the perfect match. I gave him specific things in the brief such as; the character must plummet down the stairs like he is falling out of a plane, we want to leave all sense of up and down as well as breaking all the rules as to where a character leaves one side of the screen and re-enters the other side to deliberately to confuse. I can’t speak on behalf of Roy, he is an amazing, unique genius but he would sketch stuff together, shoot it on the video line tester to try all sorts of things to find an interesting effect. I then had to animate the character afterwards to make it look like he had been done first and that he was determining the movement of the backgrounds.

One of the remarkable things about this film was that it was completed traditionally using pen, ink, paint and cell.

There were two reasons behind this, one was almost sensual. I do a lot of digital work working on commercials using the cutting edge technology, but because this film was a relief to me from my day job I just wanted to go a different way and get my fingers covered in paint and glue and bits of celetape. I just find that a very satisfying sensual experience. I had the chance to meet Nick Park a while ago and, he talks about getting the thumb prints in the Plasticine on his work and its the same, there is something slightly handmade about it that I like about using real paints. The other reason is that I had a stack of material up in my attic just sitting there, and thought that I need to make the film cheaply so why not use that? I had the cells and I had the paint, that was barely this side of rotting but thought of using it seeing as I don’t have a budget. Although I had worked on traditional things before that were hand painted I wanted to work on a film like this before it died out, before there were no more rostrum cameras left, I really wanted to completely understand how the process worked. If I started making the film now I would be screwed I think there are only about 2 rostrum cameras left standing in London, which could not have moved to the complexity of what we were doing with the tunnel sequence and so on.

Wally takes a drunken tumble through the underground

Was there ever a point when you wanted to complete the film on the computer or were you determined to complete this film in the strictly traditional sense?

I don’t want to sound like a luddite, because I love the new technology, and the quality of the short films being made now is incredible to see what people can do in their bedrooms. Oddly enough though I found the traditional processes got a load of bad press with people saying that they take too long but they don’t. I am quite suspicious of how digital pipeliners come into studios and say “buy our whole package” and all of a sudden your studio can only do something one way because that’s the pipeline. Why not just get your paint out and smear it with your thumb? Why go through the whole process just to fake that effect? We had some lighting effects in the film where we just shon lights into the camera lense to get lense flares, now I know you can buy packages that give you lense flares but equally why not shine a torch in your camera? It’s quicker and it’s easier and probably cheaper. Another thing I found out when doing commercials is that digital painting is obviously endlessly quicker than hand painting but on the other hand the clean up to prepare for digital paint takes about three times longer than if it was clean up for standard cell. I would do 20-30 drawings a day easily on Roger Rabbit but if I’m doing clean up for a computer I will struggle to do 10 or 12 making sure the lines are all closed etc. So in the end a scene that might have taken a week to clean up before can now take three weeks digital, so although you saved x number of days painting you have actually added on an extra couple of weeks cleaning up. It depends on how you look at it really, some things are better and some things are not, I just like the idea of being able to cherry-pick from whatever discipline you want.

Do you have a stack of 35,000 drawings eating up room in your house?

Yes I have 35,000 cels and 35,000 drawings all stacked up in boxes, not knowing what to do with them!

A little different from just saving it onto a hard drive.

I have to say that’s a big issue. I had this fantasy of putting all the finished work on a giant bonfire and sitting around it drinking champagne to celebrate finishing the film! But its acetate so it would not be very environmentally friendly! I will keep a few boxes of the work though I am sure

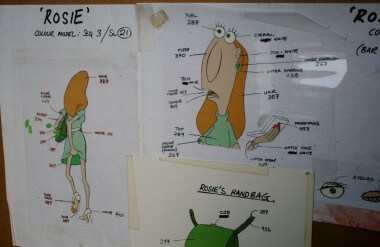

Rosie prepares for her big night

Will you continue to use the technique? Do you have plenty of cels and paint left in the attic?

Not with Xerox cels because I think I ordered the last set of cels Chroma Colour had. Its funny that so many little “destiny” things happened that kept my moral up whilst making this film, I rang up and asked Chroma Colour for 10,000 cells to finish the film. The woman nearly fell off her chair when I asked for that many, so they went to the back of their warehouse, which I imagine is a sort of dusty Indiana Jones style thing filled with endless old crates and boxes and found the cells I wanted. They had exactly 10,300 – just enough to cover mistakes for production. Odd things like that happened through production, The exact amount of colour was used for Rosie’s hair I JUST had enough for the final cell to finish that off from the last bottle to do the last cell. Every time things like that happened it was a little moral boost!

Last cel, last drop of paint could this be the last ever film made traditionally?

Actually the last Xerox we put through the machine almost exploded after we put it through, it just died! It was although the machine knew and was staying alive just for the last cell of the film! We had to get the lorry to come away and scrap it.

Guess you have no choice then but to carry on like everyone else

There is still room though to make marks on paper or frosted cell or normal hand traced cell. I worked with Richard Williams on “The Animators Survival Kit Animated”; we did a title sequence for that, based on the books cover and Dick decided it would be great to animate that. We ended up doing that on frosted cell and shooting it digitally so that was a nice example of something old and something new. I think there is a lot of room for something like that.

What’s next for you will there be a sequel to the film?

Over the making of the film I made up a trilogy for the characters – entirely for fun, I don’t think it will ever happen but it’s a nice natural progression. I am in promotion mode now, I am working with another director called Kirk Hendry who did a short film called “Junk“, I am the traditional guy and he is the digital guy but we both like each others stuff so that’s good. We are both working on a feature film script that’s in its very early stages. I also have an idea for a Christmas special for TV that if I got the money I would love to do. I have plenty of things bubbling in my mind but I need a month or two to recover from the Last Belle!