The Boy and the Heron & Miyazaki: Coming of Age Through Grief

An animated film starting with the death of a parent is nothing unusual. Disney movies have trained audiences to expect tragedy to befall a young protagonist at the start of the story. It’s an effective method of fairytale storytelling. By removing a character’s shelter, they’re left with open space to grow into.

Many of Hayao Miyazaki’s films operate on a similar principle. Well known for centering the growth of young characters, the Japanese master’s latest film is another addition to the Ghibli catalogue that sees an early separation between parent and child. Though The Boy and the Heron begins with a gut-wrenching death, Miyazaki’s movies aren’t always removing parents from children through fatal means.

There’s a difference between the journeys of characters who know they can get their parents back versus those who have to accept that they never will. Miyazaki’s protagonists respond in diverse ways which are indicative of the spectrum of overcoming grief and coming of age.

Making It On Your Own

Death is the driving force of the plot in The Boy and the Heron. The first images we see are of a hospital on fire and a boy calling after his mother while running through the flames. It also scores the beginning of Castle in the Sky, an adventure centering on two orphans. The death of a parent comes slightly later on in Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, but still plummets the titular character’s sense of reality into question.

When Nausicaa’s father, the king of the Valley of the Wind, is killed, her mourning is met with a determination to avenge him and stand up for what he believed. In this post-apocalyptic landscape, she would find a way for humanity to live as her father’s valley does, at peace with each other and nature.

Similarly, Castle in the Sky’s Pazu is another character who meets death with determination. His father was obsessed with the land of Laputa, an island in the sky. The world had written it off as a myth, and Pazu’s father as a crackpot. We meet a Pazu who holds onto his father’s belief in Laputa, he has something to prove to the world.

Other Ghibli kids who fall into the ‘determined’ bucket are Kiki (Kiki’s Delivery Service), Satsuki (My Neighbour Totoro) and Sosuke (Ponyo). However, the common thread between these stories is the lack of death involved. Kiki chooses to leave her parents at the age of 13, following a tradition of witches making it on their own to a new city at a young age. Kiki engages in an active search to find what she’s good at, what she has a passion for. Satsuki’s mother is in the hospital while her father works at a university far away. Satsuki assumes the role of the parent figure for her little sister Mei, packing her lunches and carrying her while she sleeps. Sosuke also assumes responsibility to save the parent he’s separated from when his city is flooded and his mother is trapped.

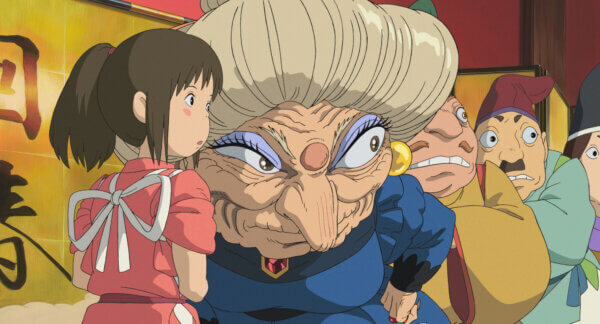

The Boy and the Heron’s Mahito more closely mirrors the journey of Chihiro from Spirited Away. Chirio and her parents trespass on a holiday resort for spirits, eventually seeing the mother and father turned into pigs and Chihiro forced to reckon with a world she doesn’t understand. Chihiro is timid. She reacts to her parents being taken from her, not with determination, but with fear. Spirited Away makes time to show you Chihiro trembling and weeping. Even before the spiriting away even begins, we see her clinging to her mothers arm, apprehensive about everything up ahead.

Mahito is similarly understated. Following his mother’s passing, Mahito seems to shut down. He talks very little. He seeks to end every conversation as quickly as possible. He stares into the middle ground when idle. He moves from Tokyo to the country, and at the first opportunity, falls on his bed and weeps in his sleep. Reality is too much for Mahito, and like Chihiro, he’s forced to grow in a universe far more bizarre, a world of both new and damned souls.

Growing up to fill the void

The lessons learned by Ghibli kids who are thrust into independence are as diverse as the situations that brought them there. In My Neighbour Totoro, Satsuki is clearly growing up too fast. At 10 years old, she feels responsible for another human being. When at school, she still can’t escape her responsibilities as Mei’s attachment to her is so strong. The lesson she learns from Totoro is to retain her innocence, to believe that something mystical can exist out there. Totoro is barely in the movie, its most famous scene is him walking into frame while Satsuki is literally carrying the weight of Mei on her back as rain pours down. He pops in to remind her that there’s more to life than your burdens.

Kiki’s growth is achieved through much more personal pain. Her job in this new city is as a delivery girl. She uses her passion for flight to be of service to the people around her, and to make enough money to support her pancake-eating habits. Capitalism soon robs her of the joy of flying. What makes Kiki unique is now inaccessible to her, exploiting her ability to fly for money, in service of people who barely appreciate it, took such a heavy toll that she lost the ability to fly at all. Kiki has to face an unkind world and figure out how to navigate it without losing the most essential parts of herself.

This message is also bestowed upon Chihiro who has her name taken from her in exchange for a job in the spirit bathhouse. In a world that wants to rob you of your identity, it’s imperative for you to find out what that is and hold onto it tightly. Chihiro’s confidence by the end of the movie comes from understanding this heightened version of reality, the tiered system of the bathhouse and the motivations behind the seemingly bad-faith actions of others. She also achieves a sense of accomplishment through days of hard work at the bathhouse.

Miyazaki’s protagonists often have to be exposed to the grind of a working day. It’s a part of growing up, but there’s also a sense of pride derived from hard work. As viewers, we find peace in seeing Satsuki prepare Mei’s lunch, in Kiki helping an old lady bake a pie, in Chihiro freeing a river spirit from pollution. Miyazaki shows how happiness can be achieved even within an exploitative system.

Mahito is no exception from the long line of Ghibli kids being put to work. In this world beyond life and death, he is enlisted by Kiriko, a sailor who feeds the souls who are unable to hunt for themselves. Mahito spends some time carving the guts of a giant sea creature, later seeing the fruits of his labour when he helps some young souls (the warawara) fly to the land of the living.

This too imparts on Mahito an understanding of the cycles of life and death. This sea creature had to be killed in order to be consumed by the warawara so they could create life. From the moment Mahito lands in this new realm, the idea of death unlocking a truth about the universe is thrust into his face. He comes across a colossal golden gate, on which the words “Those who seek my knowledge must die” are inscribed. This is pivotal to Mahito’s journey from completely shutting down following his mother’s death to standing confidently at the end of the movie.

Furthermore, this world beyond reality bonds all instances of time, meaning when his mother entered this place as a child, she was able to meet her future son. Mahito is able to bond with a younger version of his mother, to learn about her in a way that he never could, to hug her a final time. He learns that, even at this young age, his mother is okay with the idea of death. Mahito realises that she had an entire life before him, and will exist in some form after she’s gone.

There’s no right way to come of age

Miyazaki isn’t interested in showing a limited view of growing up. Though similarities exist between the journey’s of his protagonists, their situations and lessons are so varied. There are different paths to coming of age, and sometimes tragedy is foundational to sparking that growth. Leaving home and having it ripped away from you are very different things that elicit different responses.

Does pain grease the wheel of coming of age? Miyazaki’s films argue that being hit with reality is the fastest way to grow up, even if that reality is contorted through fantasy. It’s a tragedy in itself when children have to face life’s most confusing aspects when so young, which perhaps is why Miyazaki aims to express those lessons through film. Writing hard-hitting messages about the way the world works through fantasy stories is challenging, but is necessary when trying to teach audiences to maintain their innocence. Miyazaki’s flights of whimsy are not to be dismissed for the messaging nor vice versa. They’re meant to be taken as a whole, both aspects just as important as the other.

The Boy and the Heron is playing in UK theatres from the 26 December 2023