Squirrel Island: An Interview with Astrid Goldsmith

You know that feeling you get after several years of working in the visual effects industry, when all you want to do is leave London, retreat to Folkestone and make a sci-fi film action film about squirrels? Well that’s exactly what animator Astrid Goldsmith has done.

You know that feeling you get after several years of working in the visual effects industry, when all you want to do is leave London, retreat to Folkestone and make a sci-fi film action film about squirrels? Well that’s exactly what animator Astrid Goldsmith has done.

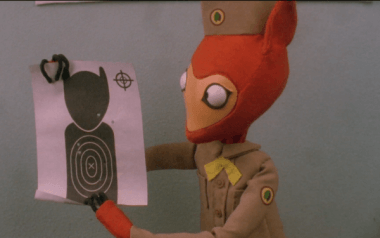

Squirrel Island is a 15 minute thriller about squirrel apartheid, following a lone renegade grey squirrel called Dot, who is trapped on a hostile and mysterious red squirrel island. Thrown together with an extremely reluctant acorn partner, Dot and her new friend uncover a horrifying secret red squirrel plot.

One of the major challenges to the production is that it’s being shot on a 1969 Bolex film camera. Just 4 weeks into production Fuji Film announced it was ceasing production of it’s 16mm stock so Astrid had to act fast and buy up every roll she could find and squirrel it away into her fridge.

The film has been over 6 years in the making and now just 6 months from completion Astrid has launched a Kickstarter campaign to help with the final hurdle.

We were lucky enough to catch up with Astrid and ask her some questions about this nutty animation…

What first inspired you to get started in animation?

I started making puppets and models from FIMO when I was 5 years old. Throughout my childhood I made hundreds of characters and scenes, anything from Tintin and Disney characters to suffragettes chaining themselves to railings! But it wasn’t until I saw A Grand Day Out when I was 11 that it occurred to me that I could make them move. I fell in love with the Cooker that Wallace and Gromit find on the moon, it has such great emotional expression for a coin-operated oven! It was the first time I’d seen stop-motion, we didn’t have a TV at home so I had missed out on things like Morph and Bagpuss. My parents gave me an old Super 8 camera for my birthday, and I started animating with plasticine.

When did you start working on Squirrel Island and what is the concept for the story?

I started thinking about squirrels about seven years ago, I kept reading newspaper articles about the impact invasive species are having on the environment and on British native species, and those articles were always illustrated with pictures of really cute red squirrels. I suppose it’s partly because they are more photogenic than other endangered species (poor old brown trout), and partly due to the popularity of anthropomorphised red squirrel characters like Tufty and Squirrel Nutkin, that they became the endangered species’ poster child. Conversely, the grey squirrel is constantly painted as a demon, a carrier of disease and a destroyer of the natural order, even though it’s entirely our fault that they are in Britain! I was interested in the way we decide between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ animals, and the policies we implement as a result. When I visited the Isle of Wight (where they have eradicated grey squirrels to protect the reds) and saw all of the red squirrel propaganda and anti-grey signage, it really reminded me of dystopian 70s sci-fi movies and I kept imagining what would happen if a plucky grey squirrel was trapped in that kind of environment. I know it’s a thorny and divisive issue, and really there are no good solutions to the squirrel problem. I’m certainly not offering any!

One of the many fascinating points about this film is that you have chosen to shoot on 16mm film using a Bolex camera. What made you choose this traditional approach over the modern tech?

I love the uninterrupted focus of shooting on film, with no video assist or computer to check your progress on I find I can concentrate on the character’s performance much better, and it also allows a slightly dangerous element of risk and improvisation! I realise that it’s not for everyone, but I just love everything about the Bolex, it’s so beautifully designed and as a maker I prefer the physical nature of film.

Only 4 weeks into production Fuji Film cease to produce 16mm film. Do you have enough stock to complete this film and does it make each frame more precious as supplies dwindle?

When I found out that Fujifilm were ceasing production of 16mm film I did panic-buy a lot of stock, more than enough to finish the film. And then I had a lot of actual sleepless nights when I was worrying that the whole industry would shut down during the course of my shoot, and there would be no labs left to develop the film. A lot of labs have closed over the last few years, but fortunately the lab I use, iDailies, is still going strong. I try not to be too precious about the film stock I have, because sometimes mistakes can be magical and I’d rather go for it and have fun than have a stressful shoot.

You mention your favourite animators are Ray Harryhausen, Oliver Postgate, Bretislav Pojar. What elements of their work do you hope to convey in your work?

I was fortunate enough to see Ray Harryhausen talk a few years ago, at one of his last public appearances. When he was asked about his characters, he upbraided the interviewer for calling them monsters, and insisted they were misunderstood creatures. I think that level of empathy and understanding is key to creating great, memorable characters, and I try to keep that in mind. Pojar, Trnka, O’Brien and Harryhausen were all masters of stop-motion animation, but from another era, before digital perfectionism arrived. The work coming out of studios like Laika and Aardman is absolutely incredible, but I think there is still room for something less perfect, movement that is more strange and ‘other,’ as that is one of the wonders of stop-motion that is not present anywhere else in cinema.

What are some of the more unique techniques you have used so far to create in-camera physical effects to avoid the use of computer effects in post production?

This summer I was shooting a fight sequence on a boat that culminates in an explosion. One squirrel throws an acorn with a lit fuse at another squirrel, and then it explodes when it hits the deck. So for each frame, I was flying the acorn (suspended by nylon wire) through the air by moving it across a wooden rig out of shot, and replacing the sparkler in the stalk each time. You can’t blow sparklers out, so I had a damp piece of kitchen roll on hand to put it out before lighting the next when it was in position, but I did burn some holes in my set when the sparklers got too hot to handle. When the acorn finally got to the deck, I lit some smoke bombs and shone a spotlight directly on explosion shapes I’d made from super-reflective orange tape, changing the shapes each frame and lighting new smoke bombs as they only burn for one minute. It took a whole day for the smoke to clear from my studio afterwards, and I felt pretty crazy. I don’t recommend it!

After working on this piece for 6 years, why are you launching your Kickstarter campaign now? How will the money raised help you complete and enhance the final film?

It’s taken six years because I’ve had to halt production at various points so that I can take commercial model making work on, which is how I’ve been able to self-fund this project up to now. But to complete the film to a high standard, I need to work with a professional post production team, and I’m hoping to raise enough to fund good quality foley, sound mixing and colour grading. The sound design in particular is so crucial in animation, so I want it to be as good as it can be, which unfortunately costs more that I can afford by myself! The campaign has been going really well so far, and if we make it beyond the target I might have enough to submit it to all of the top international festivals.

Once this project is completed, what are your plans for future projects?

There’s been some interest in turning Squirrel Island into a children’s TV show, which would be really fun. I’m already dreaming up the accompanying merchandise and theme park! I’m also writing my next film, which I’m hoping to find funding for so that I can set up a small scale stop-motion studio in Folkestone with a crew of more than one this time!

Do you hope to work in the medium of film again or do you fear you may have to take on a more digital approach?

I hope to shoot on film for as long as I can get hold of the stock and process it. I would love to shoot on film forever, but I’m not anti-digital, you can do amazing things with all formats. One of the best things about being an independent film-maker is you can make those choices without constraint.

Learn more about the project on Kickstarter and follow the progress of the film on Twitter @SquirrelFilm. Visit Mock Duck at mockduck.co.uk