Steakhouse | Interview with Director Špela Čadež

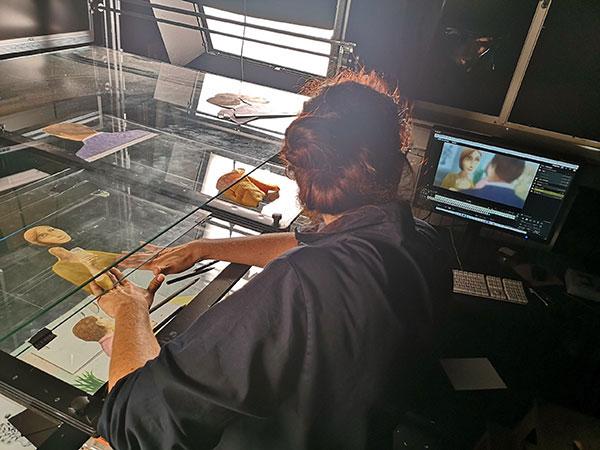

A sizzling pan, a relationship gone bad and simmering resentment are at the centre of the most recent film from a long-time friend of Skwigly Špela Čadež. Steakhouse follows a seemingly unremarkable day in the life of Liza, upturned when her co-workers throw an impromptu birthday party that disrupts her routine, delaying her return home. At home, her partner Franc begins cooking a celebratory meal – but all is not well here. Skillfully crafted, the film reflects on the suffocating but often invisible abuse that many people suffer in silence, locked away in private spaces, unable to speak out as their abuser manipulates conversations and situations, leaving the victim powerless. The film makes use of a traditional multi-plane process, as was used in Špela’s previous film Nighthawk, the soft focus achieved through the process creating further depth to the narrative as the smoke from the burning meal begins to darken and engulf the screen, creating a sense of choking and suffocation. Steakhouse is yet another great film from this truly talented artist, showcasing her flair for detailed design and poetic visual metaphor.

After a very successful festival run, winning multiple awards including the Annecy Jury Award 2022 as well as being nominated for the short animation Oscar. We were fortunate enough to get some time with Špela and dig down into the development, funding, creation and reception of the film;

My understanding is that the script was written by your partner, Gregor Zorc. Can you tell me about that collaboration?

We’ve been collaborating since my first professional film, Boles, so it’s pretty normal for us. This time it was very much his own idea, then the script and the idea were developed together. I think this was the first script that had a very strong ending but needed to be built up.

The film itself shows a form of domestic, psychological violence coming to a boiling point – what inspired this?

Mostly observing way too many couples around me who are just drowning in these toxic relationships and are incapable of realising that it’s maybe not the best for them. Actually, I realised that it’s really difficult to talk with them about it. Somehow, I feel that film is a kind of communication. It’s a very difficult topic to open up about, I think.

Image: Finta Film

This kind of weaponizing of love within relationships is really awful, but sadly, quite common in our society. What did you personally uncover whilst exploring this within the film?

Actually, I was super surprised that the audience were not reflecting on their personal relationships. Not just partner relationships, but also seeing their mother torturing them in this way when they were children, or in so many different aspects. This sort of thing is not only between romantic partners, although I think it’s strongest in these kind of relationships, but it can be in all sorts of relationships. So that’s what actually struck me afterwards, was this reflection on your own experience and even that some people don’t have, or are lucky to not have, experienced something like that and it made them uncomfortable. It is probably a bit of an uncomfortable film, I guess.

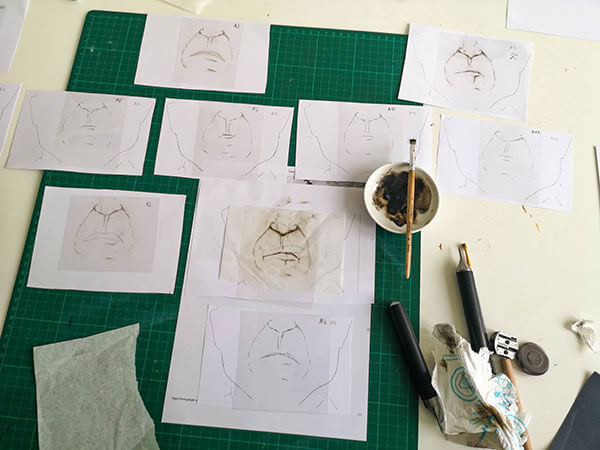

The film is also a return to your beloved multiplane setup, but taking the process even further. There are some shots in the film that I find particularly fascinating, like the bubbling of the fat on the steak. How is this achieved and what were the most interesting shots for you to figure out or do in the film?

I think the bubbling and the cooking was especially fun for my animator, she really loved all the precise bubbles. They are just redrawn with each frame, I think we combined a lot of painting under the camera with the cutouts. I think this is a very nice combination, because it can be drawn very precisely. It can actually come to life with just a little bit of highlight or shadow. My favourite scene was something that we tried a lot to achieve, which was the smoke. I always love playing with the complete, almost abstract scenes, but they are still super real, and they overtake the emotions with the visuals. That’s something I tried to achieve. But then the most difficult scenes are probably the ones that have to have all sorts of details and where a lot of layers have to move at once. And those were the ones that we were then preparing for a long, long time.

Are those the ones that you pre-animated?

Yeah. Sometimes we pre-animated and then we printed them out and coloured each frame and it was actually fun.

There was a really interesting process that you used with the cels ,where you sort of scratch into them and then seem to back-paint them with oil paint. Where did that come from?

I think this is a little bit of graphic art, like lithography. Some of the graphics are done with plastics as well, and those scratches are coming from that painting technique.

A bit like printmaking processes, such as etching?

The dry needle was a tool from printmaking. So, it comes from there.

It’s an incredibly cinematic film. The first time I watch a film, I always try to figure out how it was done and there’s some scenes in the film that, on first viewing, I just couldn’t understand how you managed to achieve. The spoon, for example, I just can’t figure it out, was it achieved through replacements?

It was replacements. But this was one of the rare scenes that was composited on the computer. We animated the man separately from the spoon. But the spoon was just a replacement. Twenty-five spoons and then it was masked into the scene, with After Effects.

Image: Finta Film

Amazing. The whole thing is just fascinating. You mentioned the smoke, which is a really big part of the film, because it kind of represents this mounting pressure that you are feeling as she is trying to get home. It sort of represents toxicity, both in choking on the smoke, but also in the relationship. Can you give me any further insight into that process, or why the smoke was so integral to the film?

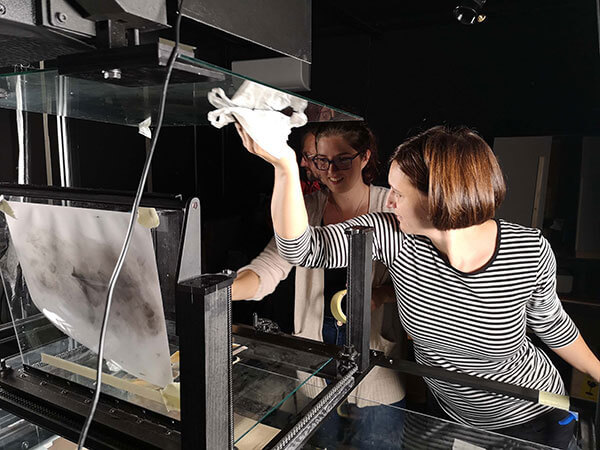

I think one aspect is showing his anger with this heavily-smoked apartment. I think we all know how difficult it is if you live in an apartment, and then if it’s full of smoke, it’s awful. Everything stinks. And if you do that on purpose, it’s already torturing the person. To achieve it we actually found this frosted cel, developed to draw with normal pencils or pastels. If you press them on paper the cutouts are sharp, but if you move these frosted cels away then everything gets blurry – that was the only effect that we used. My technician built a special add-on for the multiplane that was animatable by rolling this one glass layer up and down. This is how we animated, and it was actually beautiful because you could create transitions between one and the other. When it was completely blurry, we could do something else underneath, then you press the layer down and you have the sharpened image again.

So, was it just two planes that you were sort of moving up and down to create that kind of undulating smoke?

Yeah.

Image: Finta Film

Incredible. The ending is delightfully brutal and feels very cathartic for the central character, Liza. Do you know where that idea came from? Why did you feel it was important to round out the story in that way for her?

I think it was very important to know that this was not a onetime torture, that this is actually the edge of years of psychological violence. That was very important for the story, for all the details, her reactions, that she’s trying to not provoke even further. When the exact idea for the ending came, I think Gregor would have the real answer. But I think it was meant to be more metaphorical, that our tongues can be a weapon as well. I was afraid that it was going to be taken more in a way about eating one another but that was not my idea. It was more trying to achieve the idea of verbal violence with the tongue.

Sort of like removing his weapon?

Exactly, and that violence is very often provoked with violence, as well. I’m sometimes asked if that was my #MeToo moment or something like that, but I didn’t see it that way. I’ve heard critics say “Why is the man the one who is aggressive?” But statistically, 95% of the time, men are the aggressors. So yeah, that’s why.

Image: Finta Film

It’s interesting because watching it, it was surprising, but I remember it didn’t feel horrific, more like the natural reaction to that situation. It’s tremendously encouraging to see both a filmmaker like yourself with a film like this that uses a more classic process being shortlisted for an Academy Award. How has the journey been with the film not just for the Oscar nomination, but with the festival circuit and audiences?

I think it was received super well. I mean, I have to say that I’m spoiled with these awards and selections. It was very important for me to see Steakhouse in public. I really loved sitting in the cinema, while observing the film, and hearing the reaction. I think this is one of the loudest reaction films I’ve made. It’s very interesting that different audiences react completely differently. Like, if I was with a younger audience, they would even laugh through the whole film, but what was always common was that the public reaction was always very loud. This is always very important for me, too. During the lockdown, because we just finished the film before this lockdown started, and I was asking myself “Will we ever sit in a cinema again with an audience?” For me, having the premiere in Locarno with, I think over 1000 people in the cinema, it was just so amazing. It was so beautiful. Then just a few weeks later, I had the film online in Ottawa and I was crying, because my film is really not intended for the little screen, and especially if the resolution goes down the smoke becomes pixelated and it was so, so terrible. I was really starting to wonder, should I start using another technique that is going to work online? Or, should we make films differently? Because they’re completely different if you are imagining them for watching with the public in a cinema, or watching them at home. It’s a different media. So luckily, I think we are out of that.

In regard to the making of the film, you made it predominantly during COVID, right?

No, just the post-production. The production was, I think, a year and a half to two years, until COVID. We planned to finish in a few months, but then it was over a year before we finished the film because I had a co-production between Germany and France. The post-production had to happen in Germany and we were waiting for the borders to reopen. It was a nightmare, and I didn’t even know what still needed to be done. It was awful.

Was that just because of the global situation, or do you think it would have been hard even without that?

In the end some things were done later on in Slovenia, because it was just not possible to finish it on time and go to Germany with the borders closed. Then I realised that I would have to do the colour correction in Hamburg and stuff like that. I found out that just next door to my house, there is a great colour correction studio and I’m wondering “Are those co-productions really always necessary?” Sometimes we do it because we think we’re going to save money. But in the end, there’s a lot of unnecessary travelling.

Image: Finta Film

And how did the opportunity to actually make the film come to be? Was it after Nighthawk? And then you went into development with this?

I had another project in development, about the refugees on Balkan borders, but then I realised that I don’t really know how they feel, I don’t know what it is like to hold your child and be freezing out in minus-something temperatures. So, I decided not to make a film that I can’t be personally involved with, because that is always my motivation, that I am very personally involved with the story that I’m telling. I do believe that this makes the films stronger and more honest than just saying something that you’ve seen on the news. So that was something in between.

So then did you and Gregor have this idea for Steakhouse and go out and pitch it? Or did people come to you on the back of Nighthawk to ask if there was a film you wanted to make next?

We got some funding in Slovenia, but it was not enough. And we were trying to get German funding because I studied in Germany, and I still have co-workers that I love to work with. But they are expensive, and we can’t afford them. And then we thought it would be good to go to France, because France has a lot of money and producers. Actually, they are one of the rare countries in Europe that really value artistic animation. So, we went to pitch at Clermont-Ferrand. That was one of the experiences where we found the French co-producer. But the week before that, we found out that we got German money, so then suddenly, we were pitching for something that we didn’t really need. But pitching is still quite good to test your script because you have your first audience, you can see if the story’s working or get the first feedback from the public. That was quite nice.

Image: Finta Film

And so what’s next for you?

I’m slowly thinking of a new film, developing something, which is still very blurry. But we’ll see. You know when I finish a film, I always want to start something more experimental, less narrative. And then in the end I end up doing a narrative.

Do you think you’ll use the multiplane again?

Maybe I’m a little bit tired of multi-planes after two films, so maybe something else. I’m not sure yet. I’m really quite open at the moment.

You can follow Špela Čadež on Instagram and see more of her work on here.