Q&A with Soetkin Verstegen (“Freeze Frame”)

You wouldn’t think there would be much new to be done when it comes to animated materials; we have films made from sand, wool, wax, pixels and thousands of drawings. All of these have the one defining benefit that they, when left untouched, generally don’t move of their own accord (despite what our late-night, coffee-addled brains may think). However, when Soetkin Verstegen chose to make a film largely consisting of replacement ice, it meant she also had to work with another enemy of the under-camera process – haste.

Although seemingly ludicrous in conception, Freeze Frame sits well among the animation traditions of experimental or stop-motion animation that often uses materials sympathetic to the subject of the film. Freeze Frame is a film whose conception centres around ideas of preservation, decay and reversal, for which ice is a natural fit for its ability to sustain, kill and, inevitably, melt. The end result is a hauntingly beautiful and honest portrayal of preservation, begging the question – why do we, as humans, do what we do?

The film has recently been released online, earning itself a Vimeo Staff Pick and is among the longlist contenders for this year’s Animated Shorts Oscar nominations. We spoke with Soetkin during its festival run, during which it received a Jury Distinction at Annecy as well as awards at Clermont-Ferrand, Fantoche, Animafest Zagreb, the Ann Arbor Film Festival, Monstra and Fredrikstad Animation Festival among others.

Could you tell me about how you came to animation and your work outside of your most recent short Freeze Frame?

I studied film with a focus on script writing. It was only in my last year, on an exchange in Porto, that I took an animation class and it stuck. I think it’s interesting to work from a bit of a different background, but on the other hand, I didn’t really make short films during my studies and for a long time I found it difficult to make my first. You don’t have a portfolio to look for funding and lack the practical experience. I had an idea for a long time of what would become my short film Mr Sand. Finally I chanced upon Anidox:Residency, where I got to stay a year at The Animation Workshop in Denmark for the production of a short animated documentary. It allowed me to experiment while making the film because, ironically, I really can’t write scripts. Animation is so rich in combining a lot of interesting disciplines: light, movement, drawing, writing, sound, photography… Maybe at some point these interests will go in different directions, more towards documentary, or more towards visual art for example.

What circumstances led to the production of Freeze Frame – was it independently funded or created as part of a residency?

I stayed two months at Saari residency in Finland for the development. I could leave the sculptures to freeze outside and the sea was frozen, so we would go for walks over this big plane of ice. Then I made the biggest part of the production and animation during a ten-month fellowship at Akademie Schloss Solitude in Germany. The advantage of working in this context was that neither of these residencies demanded a fixed outcome. They are more about thinking through your artistic process and where it stands in the world around you. I love this complete independence. I like to work without a fixed plan, but add to the film as I go along. In Saari and Solitude, you are surrounded by many artists in different fields, with many different approaches and interests. It’s a great way to develop your project but also to think about how you want to work in the future.

Freeze Frame (Dir. Soetkin Verstegen)

On your website you’re quoted as saying this film features the most absurd technique since the invention of the moving image. What inspired this process of creating moving sequences captured in ice?

For Mr Sand I did a lot of research on the beginning of cinema and I think it’s a fascinating and crucial period. For Freeze Frame I was mostly drawn to early cinema’s enchantment for scientific observation and discovery. Film allowed seeing reality, time, space and the body from a different viewpoint than that of human perception. In formal elements like stretching and condensing time, reversal, inversion, decay and preservation I found a lot of parallels to characteristics of ice. Playing with these formal ideas creates a puzzle that you can connect to more universal and personal ideas. These early cinematographic explorations have a blurry line between the scientific and poetic. They are also haunting because sometimes in the process of capturing an image, the original gets harmed or even killed. In my film I hope to share a poetic experience with a bit of an edge to it

How were you able to keep the ice cold during the shoot?

Basically it’s a question of running between the freezer and the set. Then sometimes I really needed the ice to melt, and it just wouldn’t go.

Image courtesy of Soetkin Verstegen

Lighting and shadow play a key role in the film, but given that light also often comes with heat how were you able to capture these shots?

For the shots with the human figures, I was putting the blocks of ice back in the freezer between every frame, while I moved the figures. For the ice sculptures I used LED light, which isn’t so hot. They were shot separately on a plain, black background, so I didn’t need to spend time putting them in exactly the right place or order, I could do that in the edit.

Are you able to explain how you created the highly detailed skeleton shapes as well as keeping the objects that are encased in ice in place as they froze?

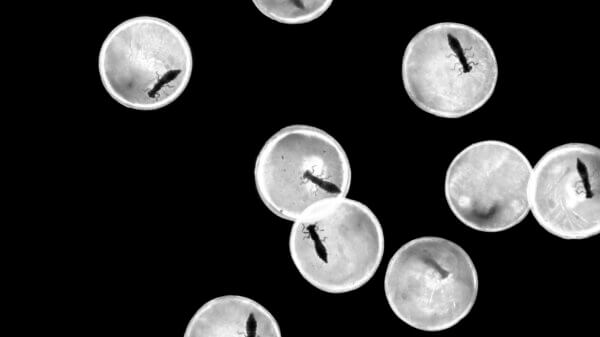

I made the ice sculptures by making replacement shapes in clay first. Then I made molds of the shapes in latex supported by plaster, filled them with water and froze them. Because the ice gets more white the thicker it is, I made the skeletons by embedding them on a higher level on the clay sculptures. To keep the figures on the same place in the water I had a few different systems to click or stick the items on a support from the back. Once frozen, I took that support away.

Freeze Frame (Dir. Soetkin Verstegen)

Also, ice tends to become opaque when it freezes unless it’s particularly pure water, how did you resolve this issue or were you happy to allow the water to organically freeze and obscure elements?

I liked that I had little control over what the ice would do. It’s like what decay does to celluloid film: it organically changes the image, sometimes makes it more beautiful and poetic, sometimes erases it completely. It makes the figures appear and disappear, like the human workers in the mist and density of the atmosphere. Just as on celluloid, the images are captured, but only in a fleeting way.

The film focuses on the tireless efforts of the men collecting ice, drawing parallels between their activities and the process of animation. What drew you to mirroring your work in their toil and what do the men represent to you as a filmmaker and animator?

The question of why you do what you do is there for everybody, but artists in particular are confronted with the question a lot. Even more in animation because it is such a slow and elaborate process for a small result. You need a lot of inner conviction to keep on doing what you’re doing. Some people asked me why I didn’t just make a fake block of ice for the puppet to drag, but it was exactly important that the process was also difficult for me. To use ice is about the dumbest thing you can do in stop motion animation, which requires stability and continuity. From one viewpoint the figures in the film are doing a pointless, repetitive activity. But to me they choose to collect and preserve something they find beautiful but know will disappear. I’m interested in seeing the relative value and futility of things at the same time. There’s a growing pressure for being pragmatic, goal-directed and topical, also in art. Something vital is missing without some uselessness.

Freeze Frame (Dir. Soetkin Verstegen)

I saw the film as part of the Annecy selection, what was it like to be part of the festival and how have you found the festival and audience response to the film, especially during the current lockdown situation?

One of the biggest compliments is when you receive a message from a completely unknown person that they liked your film, it’s the sincerest feedback you could get. I’ve been surprised on how well the film has been received. It shows me that a film can really be understood without needing to know exactly what the filmmaker had in mind and encourages me to work more in an intuitive way in the future. Of course, I have missed meeting other filmmakers this year. I don’t like zoom meetings, chats and video messages and I have hardly taken part in them. I’ve been amazed about how all those festivals managed to create an online alternative in no time, but it came with new challenges. Usually when you go to a festival you take the time off to actually be there. Now taking part in festivals is something you need to squeeze into a free moment. The possibility to be everywhere at any time is not really a positive evolution for a distracted mind like mine. In the last years I felt the need for more simplicity and focus in order to make anything and digital availability opposes that. On the other hand it was a great advantage that I could watch films from festivals that I otherwise could not have attended. That the films are not screened at the big screen is not such a big problem for me, I think internet is a great way to distribute and discover films. I already used to subscribe to platforms or watch video on demand because I’m just really interested in watching films. I hope to go to Annecy next year. You don’t need to have your film there to meet people. And to meet them in real life is just irreplaceable.

Freeze Frame (Dir. Soetkin Verstegen)

What are you working on currently/next?

A drawn animation to the sound of Magda Drozd’s Finger Touching a Stone from her debut album Songs for Plants. I was inspired by the notebooks of Colombian draftsman José Antonio Suárez Londoño to draw, scribble and think myself through the collective experiences during a residency on arts and science at ZHdK in Switzerland. The short animation will be a very distilled, associative version of this notebook.

You can watch Freeze Frame on Vimeo and find out more about Soetkin Verstegen on her website.