Red Star Alley

What is the film about?

Produced as part of the 14th edition of Hothouse.

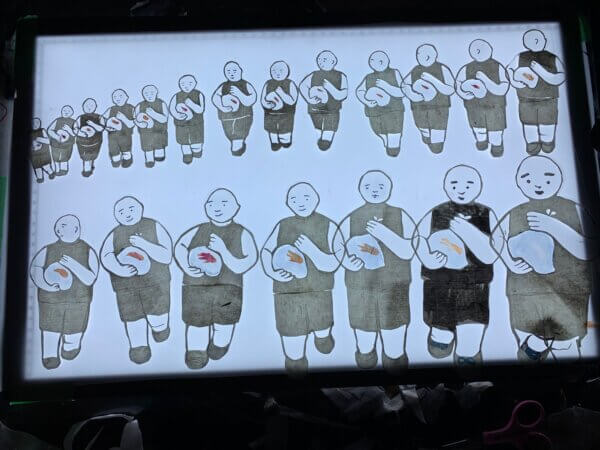

A vine takes root in old Beijing, witnessing the passage of time in a traditional hutong—part of an urban fabric that’s fast disappearing as the city undergoes radical transformation. Making ingenious use of backlit cut-outs, Jenny Yujia Shi crafts an animated elegy to a vanishing way of life.

What influenced it?

I spent most of my childhood in a hutong, an intergenerational neighbourhood in old Beijing that was mostly bulldozed during urban development in the early 2000s. The film is told through the perspective of a bottle gourd plant, a resilient fruiting vine commonly planted in the alleys. In 2022, after spotting the seeds at a garden centre in Halifax, I grew this plant for the first time since childhood. The process of planting and harvesting it in the country I immigrated to opened the gateway to revisiting memories of the days leading up to the demolition of my community, and the sight of a poplar tree that grew next to our kitchen step in the rubble. A seed is the beginning of a life cycle and a carrier of memories—a fitting metaphor for resilience, for reflecting on the loss of cherished human environments and the parts of them that live on to inform how we build new homes.

A little background information...

Broadly, I wanted to tell a story that resonates with those who have experienced the loss of a deeply cherished place in their past—whether the loss was inflicted by government policies, corporate greed, migration or other forms of violence. I also wanted to reflect on the evolving housing crisis in Canada today and the many pathways people can find themselves taking to precarious housing or homelessness. I hope to open up dialogue to reflect on the changes in urban spaces, not to idealize the past, but to reflect on what is lost and what is made possible, and how we can work with these changes to sustain meaningful connections and supportive communities.

How was the film made?

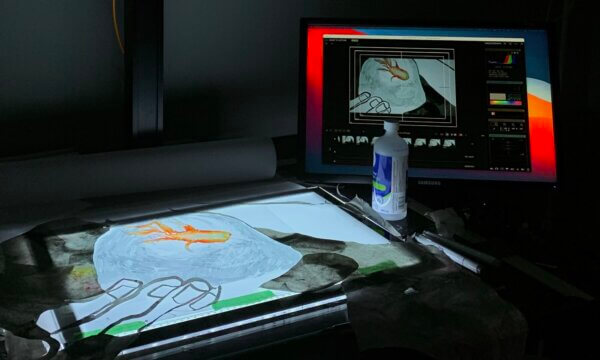

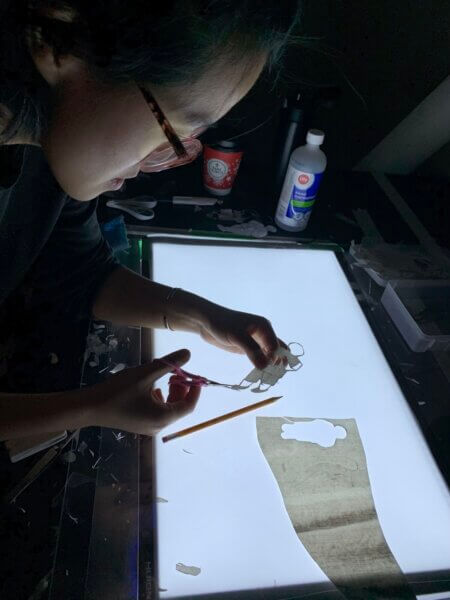

The film was made using cut-outs from mulberry paper, clear acetate and frosted mylar, where each piece was tinted with markers or ink—a process of drawing that evolved from my work as a visual artist. In some scenes, the same set of cut-outs was used repeatedly; in others, each frame was a different cut-out. To animate changing perspectives and show objects moving in depth, I fabricated individual cut-outs, frame by frame, to create a realistic representation of these actions. I worked on a light table, so the pieces were back-lit. Illuminated by this lighting, the combination of paper, ink wash and marker shading enhance the texture and tactility of the film and give it a whimsical and nostalgic feel.

Rather than being drawn on paper, or in digital software, all of the moving parts were made ofpaper cut-outs. This was challenging, as any small changes needed a whole new figure/part to be made. Some movements were easy; for any movement across the frame, the paper cut-outs could be reused. Other shots were a lot more difficult. For example, any movement away from or towards the camera, new paper cut-outs had to be made for each frame.