A Short History of Indians in Canada – Nancy Beiman Interview

If you’ve not heard of Nancy Beiman then you’re not listening hard enough. An alumni of the first Cal Arts Character Animation Course her career has seen her work in shorts, TV specials and features at Disney, Warner Bros Bill Melendez Productions, Hahnfilm GmbH, Amblin’ London, and many other studios. Through her post as professor of animation at Sheridan College and through her key texts Prepare to Board and Animated Performance Beiman has educated many in the art and practice of animation.

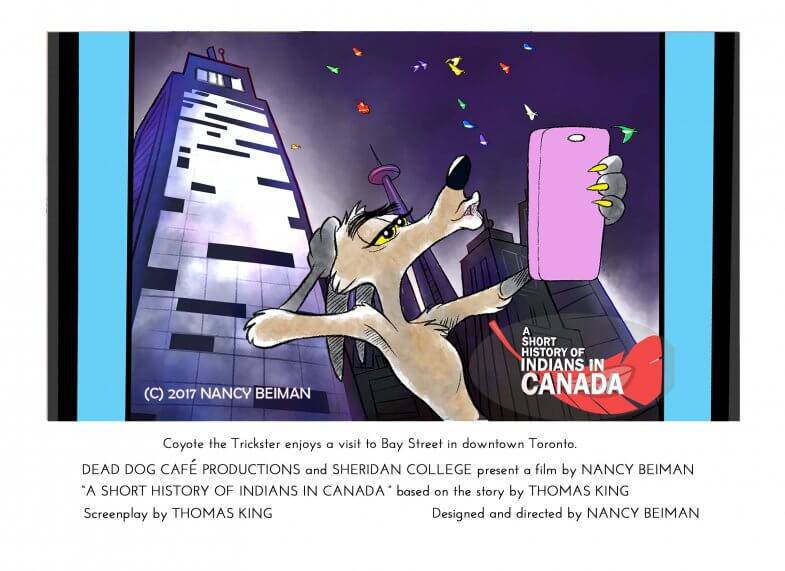

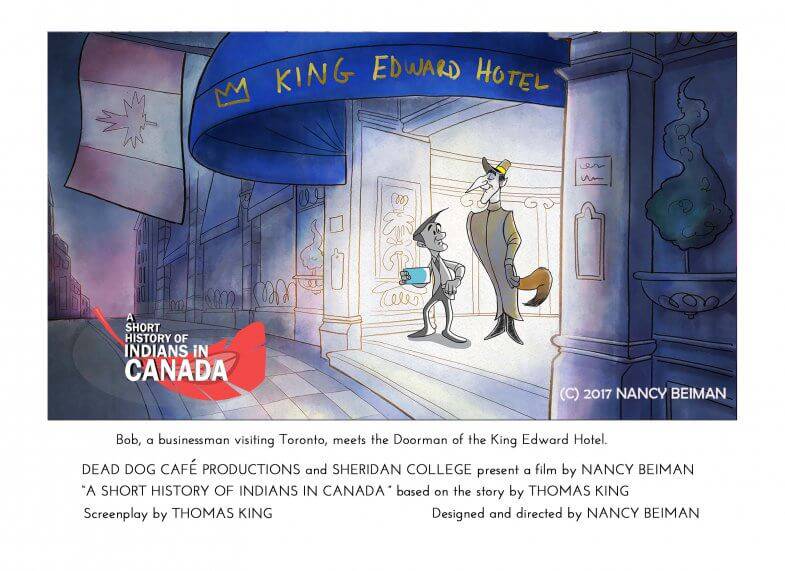

Another unheard subject (particularly here in the UK) is the plight of the first nations people of Canada. Thomas King’s story A Short History of Indians in Canada satirizes the Native Canadians’ treatment at the hands of a thoughtless, procedural government. Upon hearing that King wanted this story animated, Beiman, aided and encouraged by Ronni Rosenberg, Dean of the Faculty of Animation, Art and Design and Associate Dean Angela Stukator of the BA Animation Program, immediately set about to bring the compelling tale to the screen.

In terms of character animation Beiman’s latest film practices what she preaches and this has translated into screenings at various worldwide festivals and events including the Women Over Fifty Film Festival and Sommets du cinéma d’animation playing at the Cinematheque Quebecois in Montreal. The film has also won first prize at the Red Nations Film Festival. We caught up with Nancy to talk about the new film which you can view above.

After working in industry you have spent years teaching and writing books on the subject. How easy was it getting back into the flow of a short animated production?

I’ve never left animation production. I’ve been mentoring students’ senior and Masters theses ever since I’ve started teaching. I teach them the methods I learned when producing for my own company. For this film I used a mixture of old and new planning sheets. Bar sheets were used to cut the picture and read the track breakdown. I then handed them off to the artists since with digital animation there is no need for exposure sheets. We used digital planning sheets to manage the pipeline. No paper was used, everything was digital. I was actually learning the program I was animating in while the film was in production. The most difficult scenes, the ones that were most likely to have changes, or involved 3D characters, went into production first. There were many changes on the last scene. Animation went quickly since it was meant to look like 1950s animation. So I allowed some painting errors to remain in the film; and the character models shifted. Doorman is a shape shifter so he had no actual model sheet and his appearance changed in every scene. We kept his paint boiling to accentuate the difference from the other characters. These were grey since they saw everything in ‘black and white’. And so, we finished three weeks early and were precisely two frames over the original length.

How was the experience working with the author Thomas King?

Thomas King has worked on live action adaptations of his stories, and he understood how animation productions differ. He requested changes to storyboards and to the designs of the Doorman and Coyote at the preproduction stage. There were very few changes to the animation or backgrounds. The script also went through several revisions since some action that read well in print would have been grotesque in animation. Mr. King knew exactly what he wanted to have happen in the film, and while I had creative input on the visuals, he had final approval. I told my crew that they were lucky to work with a great ‘client’. It was a real pleasure and honor working with Mr. King.

The subject is an issue that continues to provoke. How have different audiences received the film?

This is an animated cartoon about a government’s not so benign neglect and attempted erasure of Indigenous cultures. Grotesque cartoon characters discuss death and destruction with very dark, satirical dialogue. Some of the lines have double meanings. When we were making the film, I wrote Mr. King to tell him that some of the crew (all young women) were getting a bit uncomfortable working on some scenes. He replied that he has had a long career making people feel uncomfortable with his writing. The difference with film is that you are seeing images that were only suggested in the story. The images sometimes literally, sometimes symbolically, describe a cultural genocide. I screened the work picture for a group of people after reading the story (which is only three pages long.) The audience laughed at the story. They did not laugh at the film. They were now able to see what they had been laughing at, and it disturbed them. I guess the film is not for everyone but it may be the most important one I’ve ever made. I have always wanted to make a ‘meaningful’ film. I’ve also wanted to make a horror movie. This film is both.

Can you tell us about the production process, how and where it was made?

I began the adaptation in January 2017, and worked on storyboards at home until March. This was while teaching full time at Sheridan, by the way. I did the boards on weekends. Mr. King and I met once at his home but corresponded afterwards via email. The music was by my late father–my sister found an old score just as I was starting the film, and it had the right, mid century, almost UPA-soundtrack quality. I edited the animatic to this music. Thomas King produced a splendid drum score for the finale. There were two revisions to the animatic, but it fell together very quickly. Production with a crew of eight students began at Sheridan College on May Day and wrapped on July 12. The final mix was on July 24. So this is a very young film. It’s just going out into the world. I would like it to be seen, but don’t expect it to win any prizes. It’s too raw.