Crab Day | Q&A with BAFTA winner Ross Stringer

UPDATE 18/02/2024 – Crab Day has won the BAFTA for British Short Animation in 2024

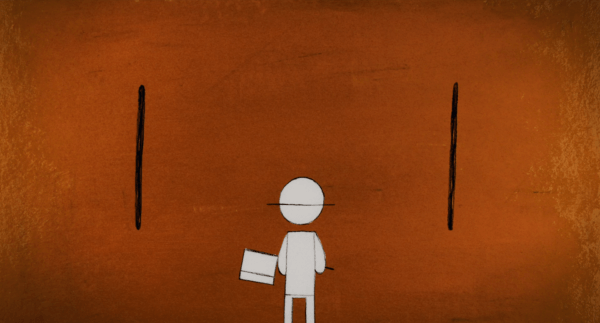

Among this year’s crop of BAFTA-nominated animated shorts is Ross Stringer’s Crab Day, the story of a sensitive boy forced to find his own path in a macho environment. Developed during Stringer’s time at the National Film and Television School (NFTS), Crab Day’s themes of masculinity and coming of age are expressed through a minimalist, sketchy art style with very little colour or background elements.

Crab Day finds its brilliance in the range of emotion conveyed by mouthless stick-men and an increasingly large crab, as well as the propulsive rhythm propagating throughout the short. Stringer sat down with Skwigly to discuss the nomination, his decision to go with a minimalist style and his personal connection to the story.

What was your reaction to being nominated?

I was driving when they were announcing the awards. I had the live-stream audio on in the car while dropping a friend off at the train station and we’re listening to it the whole way. Then we realised they didn’t announce the shorts. So we were panicking, like, ‘did we get nominated or not?’ My friend tried to look it up on her phone and she looked at the long list by accident. I didn’t know for a good 20 minutes what was going on. I stopped on the way home because I was too curious, looked it up, saw we got nominated and gave a big “yeah!” in the car on my own. I rang up my sister and we just talked about it. It’s really weird, surreal news so you feel like you have to talk to someone about it to understand what’s going on. It means a lot for opportunities that could open up and yeah, good news.

How was the experience of touring with this film?

All around pleasant. The first place I went to with the film was Anibar in Kosovo which was a super cool festival. We won the Audience Award there so I felt really involved in their community and they really liked the film. We took it to France back in December and screened it every day for school kids and teenagers. I’ve realised that kids as young as five can watch it. My niece, who is four years old, watched it when she was three and understood it. And then you get adults, everyone’s mum would come up to me and say that they really loved it and then maybe the dad would be like standing in the back giving a nod of approval, which felt very fitting for the film.

Can you talk about where the story came from?

So I grew up in Great Yarmouth, it’s kind of a rundown town, to be honest, but it’s beginning to be a bit more interesting. I still love it. I took a lot of inspiration from what was going on around me. Yarmouth has this huge fishing heritage and I was just really absorbing it. I did this workshop for my first project at the NFTS where I got paired up randomly with a writer and we had to look at paintings and try to make up stories from them. I gravitated towards all these paintings of old fisherman, or done by old fisherman, or like seaside scenes and all that. They’re always really interesting and naive and playful. And so that’s kind of where the style developed as well.

For the story, the boy and the dad are me and my dad. I grew up fishing as well. I have this one specific memory of when I had to kill a fish for the first time and that was this ritual in my head that was a step towards becoming a man. I got really interested in the idea of rituals and what they mean and how you can subvert them. We ended up talking a lot about themes of masculinity and how you can find your own meaning of what it is to be a man.

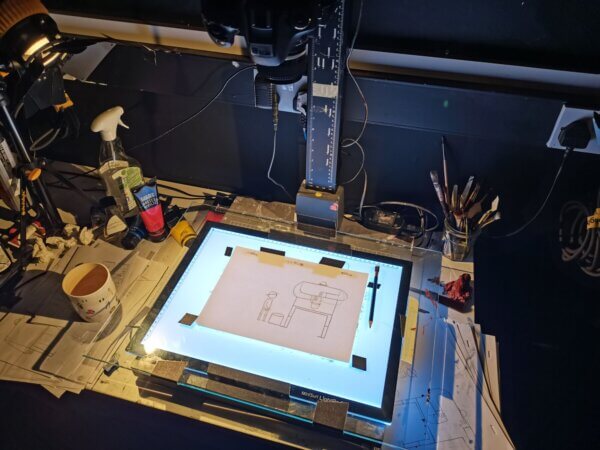

You’ve worked with lots of different filmmaking styles before, what made you go with the sketchy 2D look here?

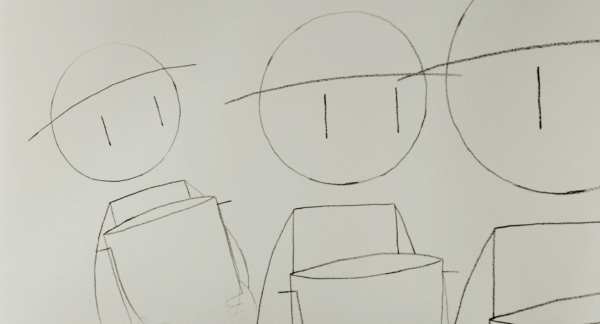

I have a habit of trying out everything I possibly can. I really like analogue stuff, just because I think it has a lot of soul in it. I like working with my hands, whether it’s with a pencil or charcoal or whatever. I think you see more of the filmmaker in it that way. Also, I was looking at a lot of drawings from when I was a kid because I wanted to capture that childlike perspective. My mum had kept things from when I was like five or nine or whatever. There was no sense of self consciousness. I wasn’t thinking about if it’s gonna look good. There was like this one drawing of the Cheese String man which was just so cool and boxy and fun and I looked at that and thought, “Wow, I have to do something that’s just simple and boxy.”

I was also looking at Alfred Wallace’s paintings. He was a painter back in the 1930s and he was a fisherman. He had no art educational background, he just painted scenes he knew. They’re all really broken perspectives and they were childlike. Then I was looking at a lot of cave paintings too. I feel like cave paintings channel that purist approach to depicting something. That’s why we didn’t have many background elements as well, because you don’t see that sort of thing on these drawings. I remember seeing, I think it was a deer or bison or something, it was drawn really huge and the village people were drawn around it really small. It communicated this idea of the cultural significance that the animal had to that community. That’s where the idea of drawing the crab really big came from.

Does having stick-man characters increase the difficulty of expressing emotion?

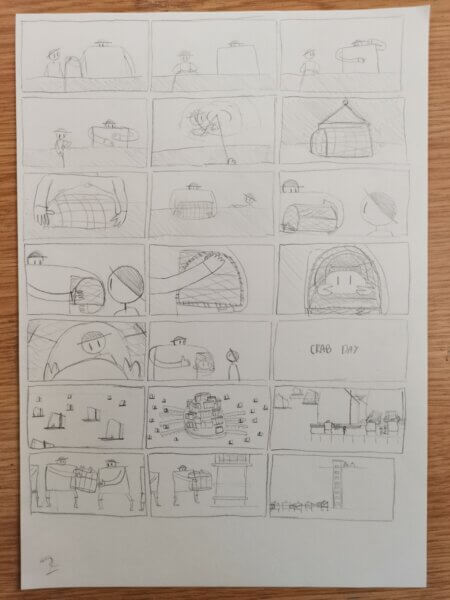

From a pre-production point of view, it’s very difficult because you’re storyboarding these really simple stick characters and putting them in an animatic. I found that a lot of the time, I could see it working in my head when it was going to be animated, but people don’t see the emotions portrayed in still images as easily. So you had to really try not to second guess yourself when they were like, ‘it’s not working.’ I found that once I started animating and once it started moving, the characters and their emotions became much easier to read. I think the context the characters are placed within does a lot of the work. There’s a bit where the boy is hitting the crab, and he looks down and then looks back up.

You’re not giving super exaggerated facial expressions, but you’re giving enough of a clue for the audience to fill in the gaps of how he’s feeling. In a lot of ways, it makes it easier, because you just let your viewers do the work, but then there are other things you have to consider. For example, a lot of emotion is in the eyebrows of the character, but I really wanted as little lines as possible. But I found that if you use the brim of the hat, how you angle it, and how you push it up and down, it works as if it’s eyebrows. So when the men are grumpier, you close that line down onto the lines that represent their eyes, it makes them look tougher or grumpy. It just takes a lot of playing around.

A lot of the short is set to a rhythm, how do you pull that off?

I’d say it’s not very difficult when you have a sound designer as good as I had. Simon [Panayi] just understood how I would think about a scene and how I would imagine it would sound and he was very good at interpreting that in his own way. To pull off the rhythmic thing, we decided to do it in animate loops, so if there’s a beat every second, a loop needs to last two seconds, and then that syncs up with the rhythm. It’s not super complicated when you’re working with someone else but I couldn’t do it on my own, I think I would just be really confused. The rhythm was really important for us because we wanted to give the idea of this community working like a machine. They’re like cogs, there’s nothing that interrupts it other than the boy when he feels slightly out of line. That’s why we have that shot of him being bumped into in the queue because he doesn’t fit into the rhythm.

Changes in lighting in 2D animation are always difficult to pull off. What were the challenges of that nighttime sequence?

It’s still a challenge to watch that scene because when you take it to different screens, it’s either really nice and you can see it, but sometimes you really can’t. It’s not perfect, but I think it works well enough. The sound also does a bit of work with carrying the tension. I think it’s probably the weaker part of the film but I knew I needed the nighttime scene and I wasn’t quite sure how we were going to portray it. We did it mostly in the grade at the very end, we took the levels of the paper down. Maybe we took it down a bit too much, not too sure.

How would you celebrate a BAFTA win?

Well, my cousin sent me a bottle of champagne, so I’ll probably open that. I think there’s an after party so we’ll be partying. Even if we don’t win, the other two films are fantastic. I’ve met the other nominees now and they’re really lovely. I think it’s just going to be a celebration of the work.

This year’s BAFTA ceremony takes place on Sunday 18 February on BBC One and iPlayer and broadcast around the world including on Britbox in North America.