Interview with Rafael Sommerhalder (‘Au Revoir Balthazar’)

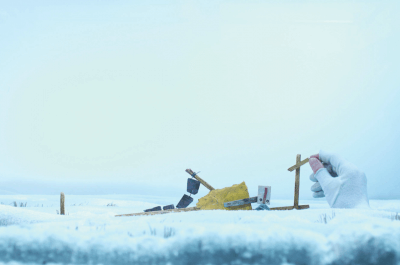

Rafael Sommerhalder‘s films are well known for their simplicity and whimsy, both in design and approach to storytelling. His new film Au Revoir Balthazar, created using the classic multi-plane stop-motion technique, uses a mixture of found organic objects for both the puppets and scenery, weaving together a subdued palette that immerses the viewer into hazy summer days and crispy winters mornings. You wouldn’t think it was possible to deliver so much emotion from what is essentially a couple of pieces of wood and some wire, but imbuing any old object with life, soul and believability is what keeps the idea of stop-motion alive in its purest form.

We were able to get a little time with Rafael to talk about the project and just why he went down the sometimes complicated route of stop-motion for this, his most recent film.

What led you to animation?

I studied at a normal film school in Lausanne in Switzerland. And there was a man called Claude Barras who you may know who was a fellow student, who was in the CGI department. I saw him doing little After Effects films at the end of the 90s and I got kind of infected by the animation virus. I had to make a graduation film and normally in my school people made live action fiction or documentary films – I pitched to make an animated film. Then I founded a company with a friend from school called Zita Bernet and we made commissioned documentaries but I still wanted to make animated films. I made one in 2004 – Mr Würfel – that was my first film made out of school.

The films I know you best for are Wolves and Flowerpots that you made at the RCA. Can you tell me a little more about that experience?

So I was working in Switzerland for several years and then I had the desire to go back to school. I liked the films that were coming out of the RCA, so I applied and was rejected, but on my second time of applying it worked out and I got in. Flowerpots was the first film I made there, the challenge for my graduation film Wolves was to try and make something with more emotions, as my films up to that point had been a little dry and brainy, so that was the first film with two characters interacting – that was really the main challenge to make a more emotional film. It came from trying to remember what it was that I liked about cinema in the first place – when I go to the movies I like to see films that touch me emotionally and I tried to achieve that in my work.

Would you say cinema has an effect on your films?

I really like to go to the cinema, but I go as a normal person, like a spectator, not analysing the film. I like to be carried away by the film, absorbed in the story for a few hours. I think my films are very simple and linear narratively not very experimental. That probably comes from seeing feature films that are more classical dramas.

Your previous films were primarily 2D, what prompted a move into 3D/stop-motion? Or perhaps what came first, the story or the process?

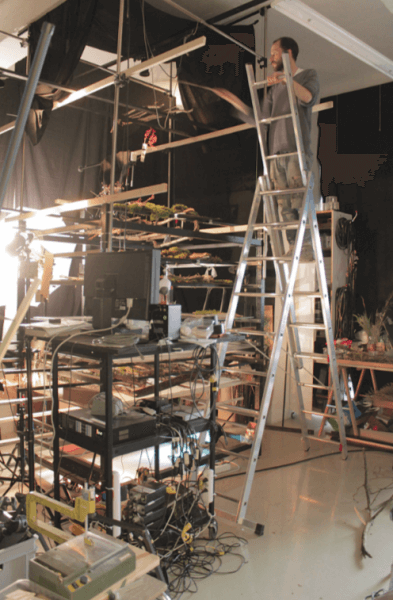

I think I had the story from the start but also l really liked multi-plane films and I really enjoy using my expertise when building stuff. I miss that sometimes, with the computer it’s static. It’s just a way to work with materials. I like inventing stuff, finding practical solutions to rig them, it touches different parts of your brain.

With your film there’s something very visceral and tactile that you don’t often see nowadays as things are getting more streamlined and pushed to be as clean as possible, the textural quality and inventiveness of your film really stands out…

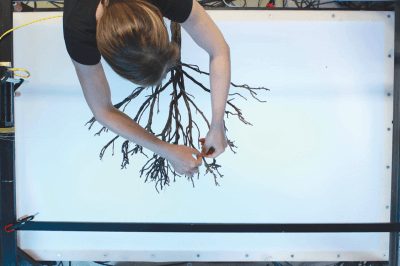

I think details are very different. We spent a lot of time trying to find the right texture for things and so it fits together and makes sense in the scale of everything. Like the grass at the beginning, we try to find everything in the forest and nature. There’s practically nothing that is plastic or painted.

How did this film come to be? Did you pitch for a budget, or simply just go ‘I want to make this film now’?

It had a nice budget actually from state funding and regional funding, which we got quite easily, actually. Not sure why. The film changed quite a lot. In early 2010 we got funding, and the production time was very long so the money almost ran out.

Narratively the film deals with rather big themes like life and adventure – what prompted that narrative thread?

I don’t really know where the idea came from. I think in the end the film was about life and death. I like the scarecrow character who can’t move actually and all of sudden he’s able to move and go on his first and last journey. I like that basic idea, which I think was the start of the story. I wanted the film to have a deeper meaning, less superficial; it’s simple but in the end it sorts of flips and in retrospect you get a much deeper meaning from it.

I always try to simplify things to get to the essence of the narrative and also in the design, this one turned out more complicated and textured, but I think the multi-plane technique gives a great perspective. Everything is from the side but also flat. It’s like a two and half D world.

What would you say were the main advantages and disadvantages of using the technique(s) you did?

The advantage is that if you really physical lighting and materials that have a colour of their own and come from nature they fit together nicely and organically and you don’t have to invent your colour palette or textures, it’s already there. That what I really liked about the process. On the negative side it just really takes so much time, to do this stuff.

Who worked with you on your film, and what did they bring to it?

Producers Claudia Frei and Stella Händler also produced my other film Mr Würfel, they agreed to produce this film with me too and they were quite important. Some people think producers just bring the money in, but they were really involved. Like, I could call them five times a day asking which feathers they preferred! It was a very important relationship for me to have someone to talk to and bounce ideas off of. Then there is Zita Bernet who I have the company with, she helped with building stuff and lighting, she was deeply involved also in the design process. We just learned together. Then there is the sound designer Zhe Wu, she’s based in London. And there were the two wonderful musicians Hansueli Tischhauser and Tobias Preisig who made the soundtrack. But that was about it – a small team but all very important and generous with their time.

Your film is making the rounds now, and audiences have been reacting well to it. How do you feel about that?

It’s nice. I make films that people get to see and I spend a lot of time making them. So I try to send it round and push it a little bit, and it’s nice when people see it and respond to it. Some people tell me they like it and have been moved by it which I really like, as the character is so simple I wasn’t sure if I’d be able to get much emotion across.

What’s next for you?

I think I’ll make a film again, but I don’t have a specific idea yet. I’m still a little burned out after this one but I’ll be back. I’m not the kind of person that has a drawer with lots of ideas and I can just pull something out, I always have to start afresh.

For more on Au Revoir Balthazar visit the film’s official website or check it out on Vimeo on Demand. See more of Rafael’s work as part of Crictor on their Vimeo page.