How ‘The Tale of the Princess Kaguya’ Defines our Relationship with Space

Deep inside a forest, a bamboo cutter discovers a baby princess. Later named Kaguya, the princess was sent from the heavens following her desire to experience humanity and its range of emotion. Living the life of a farming villager before being whisked to the capital to be hailed as a monarch, Princess discovers the aches and restraints of human life. Isao Takahata’s adaptation of this tale set itself the most abstract and elusive goal, to depict the spectrum of human experience on a microscopic level. He did this by centering an element of human life sometimes ignored and often avoided – space.

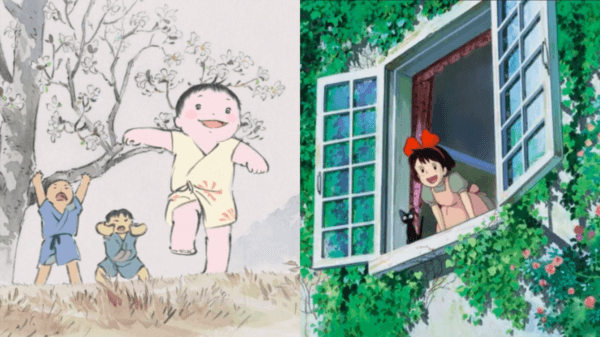

The unique art style of Isao Takahata’s The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (released 10 years ago today in Japan) is founded on leaving space on the edges of the frame, giving the effect of animated sketches on a piece of paper. Additionally, much of Studio Ghibli’s storytelling mechanics rely on the idea of Ma, literally meaning space and allowing for quietness in a film. Princess’s journey itself starts in space, as she is sent to earth by her community of spirits on the moon. Finally, space is seen within Princess as she suffers a depression resulting in the absence of emotion, an inner emptiness.

It is easy to define our lives by the things that we did, the way that we filled our time. Takahata’s film is an argument that tackling the space and emptiness that rests inside and around us is the key to unlocking the most true human experience.

The Space Between Frames

The contrast between the art style of Kaguya and Ghibli’s typical bright, rich, full frames of colour is stark. The film uses colour modestly. The earthy green of a bamboo shoot or the pale pink of a fine linen are spots of relief from the oppressive whiteness which glues the film together. In Kaguya, there are no blue skies, just the space of a blank canvas making up the edges of the screen.

Kaguya’s art style makes you intensely aware that you are watching a series of handcrafted art pieces lovingly stitched together into a story, an undeniable ode to the power of animation. The use of empty space also works to draw the eye of the viewer towards the minute details of each shot.

This technique of giving expression to the line and leaving blank spaces so that the entire surface of the painting is not filled, which engages the viewer’s imagination, is one that holds an important place not only in traditional paintings of China and Japan, but also in sketches in Western drawings. What I have done is to attempt to bring this technique to animation.

-Isao Takahata, Den of Geek (2015)

This is a film where the intricacies of facial expressions, the beauty of an animal’s movement and the elegant simplicity of nature’s design are all vital to understanding its message. Filling the frames with space allows for direct communication with the audience but with an interpretive twist. Kaguya’s paleness divides itself from the sensory feasts of the Ghibli canon in order to reflect the journey of Princess, an empty-hearted angel whenever ripped away from the joys of nature.

The Space Above Us

A tale about the spectrum of human experience would not be complete without a dash of spirituality. Princess herself is a deity who arrived from the moon. Her origin taps into a mystical reading of outer space which humanity has carried since the inception of critical thought. Many cultures assign spiritual significance to the celestial bodies which rest in the space above us while even an atheist would be filled with wonder at the idea of leaving footsteps on another world.

Kaguya uses our innate fascination with outer space to draw comparisons to social class. Princess’ tale finds her feeling free and joyful living off the land as the daughter of a bamboo cutter, feeling claustrophobic and melancholic through her time as a wealthy monarch, and feeling absolutely nothing at all as she returns home to the moon, where she is required to be emotionless.

As the poor look up to the rich, and the rich look up to the gods, each dreams of the power and wonder that the other experiences. Kaguya is a cautionary tale of materialism, how wealth drains you of your humanity and rips you away from the root of human experience, to experience a full range of emotion and to be connected with nature. The use of space, though in a different context, is again vital to establishing a hierarchy of power and joylessness.

The Space In The Plot

The weave that stitches Ghibli movies together stylistically is composed of more than the popping visuals and Joe Hisaishi soundtracks common to many in the studio’s library. The films of Ghibli adhere to a unifying storytelling philosophy – ‘ma’ meaning ‘space.’

[He clapped his hands three or four times.] The time in between my clapping is ma. If you just have non-stop action with no breathing space at all, it’s just busyness, But if you take a moment, then the tension building in the film can grow into a wider dimension. If you just have constant tension at 80 degrees all the time you just get numb.

Hayao Miyazaki, rogerebert.com (2002)

According to Takahata’s fairly talented colleague, space is a storytelling necessity. Kaguya takes that idea to heart. Being the longest Studio Ghibli film and one with relatively low stakes, the big ‘events’ in Kaguya are spread apart. The plot’s abundance of space again brings focus on the intimate details of Princess’ life, allowing the audience to experience daily existence as she does.

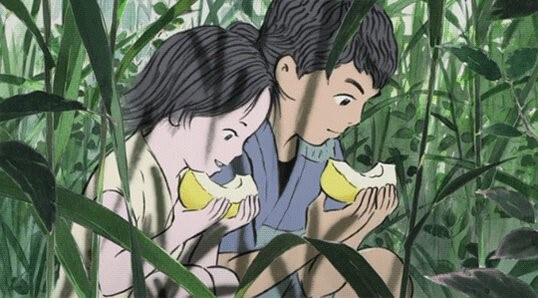

These instances of ma also act as microcosms of Princess’ emotional state at that point in the movie. When Princess crouches in some bushes alongside Sutemaru, a fellow member of her village, and chomps on slices of melon, the joys of its simplicity and her connection with nature are explicit.

Image: Studio Ghibli ©

Similarly, later in the film when Princess is on the verge of returning to the emotionless moon kingdom, she sits and sings of the birds, bugs and beasts of Earth, exuding a deeply painful regret about how she spent her time as a human.

So often we leave Ghibli movies with moments other than the big set pieces at the forefront of our minds. Chihiro and No Face on the train, Satsuki and Mei waiting for the bus, the moments that say everything without uttering a single word. It’s in the quietest moments that we feel most connected to our humanity, and the quietness of The Tale of the Princess Kaguya utilises that space to embody the human condition.

The Space Inside

The presence of space in the technical filmmaking aspects of Kaguya all exist to serve the emptiness at its centre – Princess herself. Her envy of the complex lives of humans led her to entering the human realm to experience those multitudes, only to be faced with a society that looks to quieten the personality and expression of women.

When Princess’ adopted father discovers small hills of gold and springs of the finest linens inside bamboo stalks, he decides that she is destined for the height of human wealth and comfort. Princess, however, found joy in the humility of her life before the riches. She found community with Sutemaru and found wonder at the intricacies of nature. While still a child, she shed a tear singing a nursery rhyme which becomes a motif of the film, something that declares her desire to remain without riches and connected to nature.

Go round, come round, come round, O distant time

Come round, call back my heart

Come round, call back my heart

Birds, bugs, beasts, grass, trees, flowers

Teach me how to feel

If I hear that you pine for me, I will return to you

– The Tale of the Princess Kaguya

As Princess and her family enter high society, she begins to rebel against the expectations for women in this social class. In opposition to having her eyebrows plucked and her teeth blackened, she exclaims “Even a princess must sweat and laugh out loud sometimes! Or want to cry, or get angry and shout! … a ‘noble princess’ is not human.” Princess only has so much fight in her. After her father insults her “hillbilly” friends from the village and begins the process of getting her married off to a wealthy prince, Princess’ spirit breaks.

For long stretches of the movie, Princess exists as an empty vessel, embracing the void of space as she had been taught. Even when gifted a pet bird by her father, she immediately releases it from this place of entrapment, rejecting the joy that nature once brought her. During a rare outing from the mansion to see the blooming cherry blossoms, Princess allows herself to frolik in their beauty before bumping into a small child. Before she can turn to apologise, the child’s family are on their knees asking for her forgiveness. The invincibility afforded by her wealth and status is unnatural, and it sends Princess deeper into her emotionless state.

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya is asking us if strict adherence to the rules of polite society is worth it if it means inhibiting our natural instincts. Princess chose to be on this planet for a specific reason. She got a taste of what it’s like to fulfil the purpose of existing but had the societal structure of humanity rip it away from her in the name of ‘nobility’ and social status. If the poor cannot experience joy without wealth and if the wealthy cannot experience joy without freedom, then what’s the point of any of it? Princess’ emptiness reflects the emptiness every person goes through. The moment when you realise you took the wrong path, that the thing you desired hasn’t made you happy, when you question the world that pushed you to the edge of your emotional limit, begging to feel nothing at all.

Go Round, Come Round

“Use up all the trees and you kill the mountain. Leave its power and go away, and it revives. Give the trees ten years and you can work them again.”

“But what if the mountain really is dead? The leaves were so beautiful…”

“It’s not dead. Look, the trees are getting ready for spring”

– The Tale of the Princess Kaguya

The above conversation takes place during Princess’ fantasy. She runs away from the mansion, back to the village only to find a different family living in her old home, the trees to be leafless and her old friends nowhere to be found. It should be the rock bottom of the film, the moment where she is most alone, abandoned by her father, her friends and by nature and life itself.

However, the small conversation that takes place with a coal miner lights a faint ember of hope. Her old way of life is dead, the person she was as a village child will never be recoverable, the experience of human life has jaded her to the point of numbness. But Princess’ disconnection from nature has caused her to forget the cycles that our world goes through, that seasons eventually fold into one another, that spring will come again.

Once we stop mourning the death of the life we wanted we can plant new seeds of hope for the life we can build from here. This blissful moral is a faint light in the darkness of The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. By the time Princess learns this lesson it’s perhaps too late for her to change. Despite this, that conversation is vital to completing the arc of the film. Princess came to us to understand the human experience, and there are few things more human than the discovery of hope in the trenches of despair.

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya defines the human connection to space. It leaves the edges of the frame to your imagination, it teases us with the mystery of the emptiness above our world, it allows us to interpret our own meanings from the space in the plot and gives us hope that the emptiness inside may not last forever. Kaguya shows space to be ill-defined and abstract, letting us see what we want to see, and mould our futures into what we want them to be.

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya is available to watch on Netflix