Pom Poko at 30 – Subverting the Talking Animal Movie

Declaring that some stories “need to be told in animation” comes with a lot of baggage. Animation is a medium that knows no bounds, limited only by the imagination of its creator and the bank account of its financier. So, with all that possibility at its fingertips, why does so much animation default to making animals talk? It’s possible there’s some anthropological reason as to why humans feel so keen to anthropomorphise beings and objects, but at this point in film history, the animated movie centred on cute, wisecracking talking animals has become a trope and an easy way to appeal to children.

Even if the endless possibilities of the medium weren’t narrowed down to that particular lane, to say that animation can only be the home of stories that break reality is boring and limiting. The late Studio Ghibli co-founder and director Isao Takahata understood this, making multiple grounded, human dramas that were elevated, not always by surrealism, but by the simple fact that they’re composed of beautiful drawings.

Takahata’s first film with Ghibli, 1988’s Grave of the Fireflies, was described by famed critic Roger Ebert as “an emotional experience so powerful that it forces a rethinking of animation,” praising its ability to depict reality without pushing for realism. By making films like Grave and 1991’s Only Yesterday, Takahata understood that animation wasn’t just for talking animals. Which brings us to 1994, where he made a movie about talking animals.

Takahata bucked the trend of talking animal pictures being an easy route to making millions in plushie sales and produced one of the most ambitious movies in the Ghibli catalogue. At the centre of Pom Poko isn’t a group of any old talking animals, but talking tanukis, raccoon-dogs known in legend for their ability to take the form of any animal, person or object.

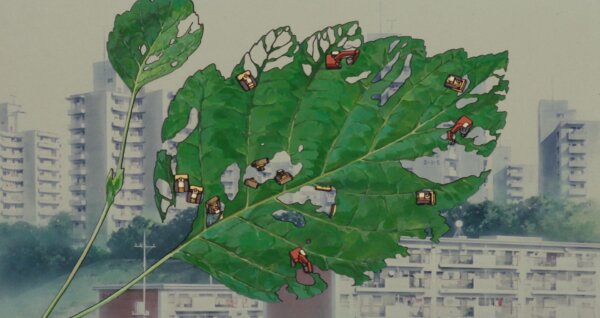

The very nature of centring a film around tanukis set an artistic challenge far exceeding the already stellar standard set by Studio Ghibli’s six feature films. Can a film work when the cast of characters refuse to remain the same shape? Not only are they routinely taking the form of other beings, but the raccoon-dogs have three different versions of looking like tanukis – a hyper realistic model, an oversimplified cartoony model and an anthropomorphised, expressive-eyed model (all shown below).

These different forms blend into one another seamlessly in the film, the animators adapting to a different rendition of each character even within the same scene, mirroring the film’s overall commentary on adaptation as the tanukis look to survive in an increasingly industrialised Japan. As their habitat becomes the target of human expansion, the tanuki have to lean into their powers of transformation to either stave off the threat or assimilate into human society.

There is a clear divide between the nature of animals and the nature of humans in Pom Poko, a feature of the talking animal framework which allows the movie to comment on humanity from an outside perspective. The film is critical of that uniquely human desire for progress and expansion, communicating its critique by putting the audience in the point of view of a group of animals whose way of life is dying.

Pom Poko forces the audience to ask whether this can be called ‘progress’ at all when so much has to perish in order for humanity’s presence to grow. Rather than progress, what humanity is really working towards is homogeny, a world where nothing is too sacred to be left untouched by concrete and metal. The humans in Pom Poko are blind to what the world loses if tanuki disappear, a species of animals with genuine mystical powers. Their existence may make the world a richer place, but has no material benefit to the everyday life of a person.

This same dynamic is seen across the real world. Global food production is causing the loss of thousands of fruits, meats and veg because every inch of farmland is being used to grow the same types of crop. When a patch of soil is needed to grow a species of banana capable of being distributed across the world, we lose the species that can only be grown in that region. When the farmlands of Palestine are ravaged by occupation, we’re at risk of losing the Jadu’l watermelon, a species specific to the country.

Humanity’s lack of understanding of the sanctity of the natural world has it running in place. Everything new we invent costs us something unique that already existed. The tanuki in Pom Poko seek to teach humanity this lesson in a sequence that hammers home the technical aptitude of the film. In order to trick the humans into thinking they’re intruding on sacred land, the tanukis hone their skills of transformation to embody ghosts, ghouls and goblins which terrorise the locals. However, a local theme park takes credit for their efforts and it goes down in the press as a marketing stunt – typical human assimilation.

Across their 40 year history, talking animals have only appeared as side characters in Ghibli films with extremely heightened fantasy elements. Many of the films carry environmental themes, but Pom Poko allows us to inhabit the part of the world that’s under threat, finding a balance between realism and fantasy to create some of the most powerful imagery the studio has ever produced.

Takahata himself carried on a tradition of innovating with art style throughout his career. Only Yesterday denotes scenes in the present day and those projected through memory by slightly draining the colour palette and leaving space at the edges of frames to show the main character looking back. My Neighbours The Yamadas employs a simplified, newspaper cartoon-esque style, the minimalism of which was rendered with watercolour on his final film, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya. Takahata has always been keen to exemplify the different forms animation can take, and Pom Poko deserves to be celebrated as one of the most unique features in animation history.