Pinocchio: Interview with Puppet Supervisor Georgina Hayns & Production Designer Guy Davis

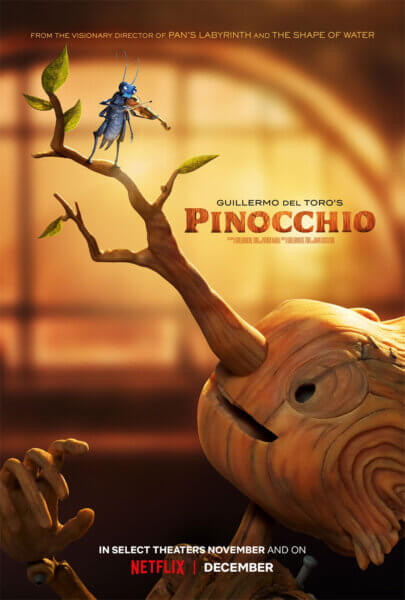

In anticipation of Guillermo del Toro‘s exciting new take on Pinocchio, set to hit select theatres next month and Netflix in December, Skwigly were privileged to speak with the film’s Puppet Supervisor Georgina Hayns and Production Designer Guy Davis.

Boasting the masterful puppetmaking of Mackinnon and Saunders (Corpse Bride), the film is directed by del Toro and Mark Gustafson (Fantastic Mr. Fox) with a script by del Toro, Patrick McHale, Matthew Robbins and Gris Grimly (who also created the original design for the Pinocchio character) and produced by The Jim Henson Company and ShadowMachine in co-production with Necropia Entertainment.

Having worked in animation production since the early nineties, Georgina’s credits include Bob the Builder, Postman Pat and the Laika features Coraline, ParaNorman and The Boxtrolls, with Guy having previously worked on other del Toro productions including Crimson Peak, The Shape of Water and the upcoming Cabinet of Curiosities as well as TV series such as Steven Universe, Mystery Science Theatre 3000 and The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power.

The film represents such a strong new look for this story, which has as much to do with del Toro’s vision as the puppets and the design. Can I ask what do you both individually think is the most unique element of the film?

Guy Davis: It’s hard to narrow down as one element because there’s so many things that play off each other, from design to story.

Georgina Hayns: There is, isn’t there? To me, it’s very much Guillermo’s look and take on Pinocchio. And very much his vision of a stop-motion film. But yeah, I don’t feel like there’s one particular character that stands out any more than any other character. What I think is really interesting is the fusion of styles. You have quite humanoid characters and you’ve got animals talking, insects talking to humans, but it all works in the context of the story.

GD: They flow together, they inhabit the same world but not in a fanciful way that stands out. Cricket seems to fit next Geppetto as much as some of the other, more fanciful characters we haven’t seen yet. [They all] feel like they could exist in this world because the world itself is almost a caricature. I mean, it’s very detailed and realistic in texture and tone, but in structure it fits the characters that have to live in it.

So Guy, you’ve worked with Del Toro previously, correct?

GD: Yeah, we collaborate on a lot of concept design. It started before Pacific Rim, since then, we’ve worked on a lot of projects that didn’t come out and a lot of projects that did, like Crimson Peak and Shape of Water and other projects. It’s always been a really inspiring collaboration working with him.

And what was different this time?

GD: Well, for one, this was my first job as Production Designer, so that was a new role for me. And of course, I was usually doing live action, so this is my first foray into stop-motion. I did the Super 8 films when I was in junior high, moving clay around and growing up on Ray Harryhausen, but learning the ins and outs of stop-motion in the business from everyone at ShadowMachine and from Curt (Enderle) and Rob (DeSue), who have a history of working in stop-motion, it was incredible to just discover it all these years later again.

Guy Davis

Gris Grimly’s original book design was a strong inspiration for the main character of Pinocchio, could you explain how and why he felt like such a good fit for this vision of the film?

GD: Well, I think Guillermo would have to answer [for] what he saw in the [Grimly’s] design. I know we started with that and we then elaborated a little bit more, influencing it with more of Guillermo’s vision, as far as limbs being different and less of a cartoon, an abstract in the shapes and a little bit more of a caricature. So it was less angular and stuff. But I know we did do a lot of revisions in the proportions, which gave him a different stance. The unfinished head was a great idea from Guillermo, because that’s Geppetto carving him, being very careful on one side, and then as the night went on, and he was in his grief and a little bit drunk, it got a little sloppier as it went. So he was sort of this unfinished design by morning.

GH: It was interesting to see the arc of Pinocchio’s design from early days, from Gris’s original to the actual final, approved design, and be a part of that, hear Guillermo’s thoughts, hear Guillermo working with Guy through it. And then of course, getting it into MacKinnon and Saunders’ hands, because I didn’t really touch much of Pinocchio on site here. It went straight to MacKinnon and Saunders and this amazing puppet maker that I’ve worked with for years, Richard Pickersgill, he was the main tech wizard on it. Richard trained as an armature maker and came and worked out in Portland with me on several of the Laika projects. Through that he learned a little bit about 3D printing, and just took on that whole world, went back to Manchester and did things with the 3D printing world and making Pinocchio that we’ve never seen before, and I think really brought that character to life.

Georgina Hayns

Could you talk a little bit more about Pinocchio’s construction?

GH: One of the wonderful things about working on Pinocchio – there weren’t secrets. Stop-motion is an age-old art form and one thing that I was trained in my early years, by Pete Saunders and Ian MacKinnon, was you can only improve the art form if you share your knowledge. I think it’s also the timing that Pinocchio came about in 3D printing, because the technology has changed enough that the different metals can be used for printing now, which lend themselves more for puppet skeletons than the metals that they started off printing with. So it was just the perfect moment in time in 3D printing, and Richard’s brilliance and understanding of armature making and 3D printing came together to make Pinocchio. We had a wonderful little moment in Portland when myself and Brian, the Head of Animation, were trying to figure out how we were going to solve the eyes. Traditionally with 3D printed faces, we split the face in half to get all of the expressions of eyebrows and eyes and everything. So Pinocchio doesn’t really have eyes, he has holes, and he also has woodgrain. So the idea of splitting a face with woodgrain was going to be a nightmare in post to fix that. So I had this mad idea, I was like, “Well look at the design, his eyes are the knots in the wood, can we just work those a little more perfectly into circular knots and take the entire eye and use that as a replacements, so it’s the eye that is the replacement part?” And by changing the eye shape, we were able to also create a brow, so the brow became a void between the eye sockets. That was just a bit of problem solving with car body filler, a hard head, and then “What do you think Guillermo? Do you like it?”

GD: That’s the thing that I love, is that there’s this communication between all the different departments, between design and building and how those feed on each other. It’s great that we can always say “Well, this is why something works in a design way” and they can say “Well, this needs to change for practical ways to work” and sometimes it brings everything back again. Now all of a sudden, this brings back to the design of his eyes being like knots, which is a very beautiful detail for the character, and it’s also a problem-solve.

It’s just perfect elegancy, when the problem-solving feeds back into the design in such a symbiotic way.

GH: They’re really special moments in puppet making when that happens.

GD: That worked out that way through the whole film, I can’t think of any character that we were disappointed with. There are difficult characters and designs that couldn’t be exactly as their concept was, for mechanics, or this or that. But the changes made it better, so it was never a frustration. It was more like “Wow, this solved the problem and made it better”.

You’ve both summarised this in a much more elegant way than I could have. But for me stop-motion has always been the art of problem-solving, and I was just wondering if there were any unique challenges that you found on the project that you’d like to talk about?

GH: For me, the eyes for the characters were the most challenging of all aspects. So with the human characters, especially, we wanted ball and socket eyes. But then we wanted silicone mechanical skins and the inherent problem with that is the minute you move an eyebrow up, it pulls a skin away from the edge of the eye, and you’ve suddenly got a big gap. So the tiniest part of all of the human designs was the biggest headache for all of us. We’ve got MacKinnon and Saunders working on it, we were working on it in Portland, we’ve got the best of the best trying to problem-solve how we could get a blink, an eye movement and an eyebrow movement without gaps appearing here, there and everywhere. And between us, we all came up with solutions but it took until the end of the movie for us all to go “Can we make the movie again? Because now we know exactly how to solve it!” (Laughs) But we all did actually say “Please can we never do ball and socket eyes in silicon skins ever again?” (Laughs) But yeah, in a weird way that was the most challenging thing, I think, from a puppet making standpoint.

It’s generally eyes and hands, are historically the hardest bit in stop-motion because they’re both so small but also completely eye catching and every human on Earth knows what those two things should move and act like.

GH: Yep!

(Netflix)

You have quite a legacy behind you, in terms of where you’ve worked and what you’ve worked on. What was the most enjoyable or interesting part of working on this project for you?

GD: I mean, it was an incredible experience. And it was unique in that, coming from live action, you’re on a production maybe a year, or year and a half, and you’re like, “Wow, that was a long production”. I started this originally back in 2012 and then, you know, we started again in 2019, and now here we are, and it’s being done. It’s a different pace and I think just seeing that passion, no one ever lost that drive or that interest over all these years about this story. And this project, it was always inspiring, it was always something that people were totally devoted to making special, it never felt like “Okay, let’s get this done”. It was like “Let’s definitely put everything we can into this”. And that was every aspect of the hundreds of people who worked on it, problem-solving, creating, and just spending the time and love to put into it. So that definitely speaks to the inspiration and talents that Guillermo brings, and Mark too, and everybody in every department. It’s just one of those things that you’re excited when you see it on screen and things are brought to life. But then all of a sudden, you think, “Wow, I was a much younger person when this started”!

GH: The fact that we all were there wanting to work together with two leaders, Mark and Guillermo, who wanted to give us all the information we needed to make a beautiful film. It was just this very special movie for me, because stop-motion films are always hard, with some crazy deadlines. We knew that the expectations were beyond some of the realms of the budget and the schedule, but we all had a wealth of experience. A lot of the crew had worked together for 15-20 years, on and off through different projects, and what we had learned over those 15-20 years is that the most important thing about puppet making and stop-motion movies as a whole is trust, communication, and information. If you haven’t got all of those three things, then it falls apart. You’ve got to trust the person next to you, you’ve got to trust in your team, you’ve got to trust in your boss. What was very apparent from the word go on Pinocchio is that we had a secure environment set up by ShadowMachine. And Mel Coombs, who is an amazing producer – I mean, at times she was a dictator, but it was brilliant, we knew she had our back all the way through. And whenever a problem arose, if things were getting too big, if things were running long, somebody would bring us together to talk about how we can solve the problem, how we can move forward as a team together. There was no blame, it was just this beautiful team effort to make something that was brought to us with love, and gave us love and we gave love back to it. There’s so much love, happiness and passion in this movie.

Pinocchio is set to be released in select theatres November 2022 and on Netflix December 2022