Interview with Patrick Bouchard (‘The Subject’)

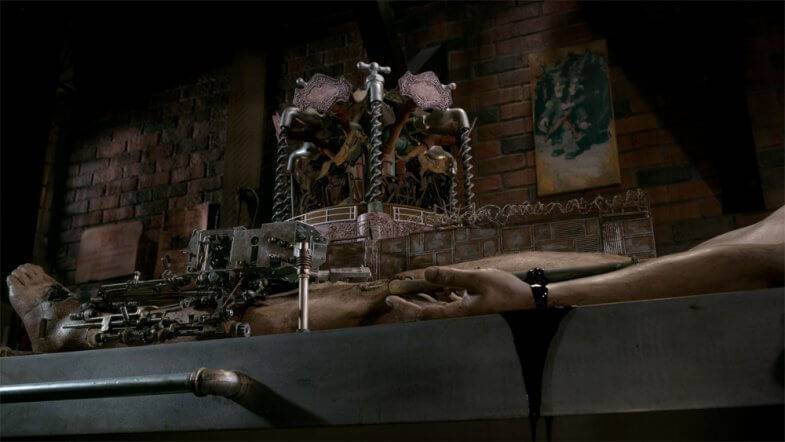

Making oneself the subject of a film is not an uncommon practice among animators, auteur or otherwise. Performing a literal and metaphysical autopsy on oneself, however, takes the practice of personal reflection to a whole other level. In noted Quebec filmmaker Patrick Bouchard‘s stunning new stop-motion/pixilation piece Le Sujet (The Subject), produced by Julie Roy at the National Film Board of Canada, we see the director take on the task of dissecting his own cadaver, extracting symbolic artifacts that represent his memories and emotions, in the hope of tracking down the root of his troubles that can be found in his own heart.

With an esteemed filmography that includes Bydlo (2012), Dehors novembre (2005), The Brainwashers (2002) and Subservience (2007), The Subject is stop-motion director Patrick Bouchard’s most personal film to date. In the spirit of the film’s intimate nature, the director took on every creative role when crafting the film, from conception through to post-production and even composing the film’s soundtrack and designing its poster.

Having premiered as the opening film of RVQC 2018 earlier this year, the film has gone on to be included in the international line-up for last month’s 50th anniversary edition of the Cannes Film Festival’s Directors’ Fortnight and is screening this week in competition at the Annecy International Animated Film Festival., with participation in next month’s Anima Mundi festival to follow.

For our readers who might not be familiar with your work, can you tell us a bit about your background and film work prior to The Subject?

My interest in animation goes back to my childhood; I was a big fan of Ray Harryhausen’s work, particularly the Sinbad and Jason series. But the Université de Chicoutimi is where I really got my start, during my degree in interdisciplinary arts. There weren’t any animation courses but I made three short films, including my final school project, Jean Levieriste. This opened the door for me to the NFB, where I made my first professional film, The Brainwashers, in 2001. The film enjoyed some success on the festival circuit. I followed up with Dehors Novembre in 2005, Subservience in 2007, Bydlo in 2012 and The Subject in 2018. Stop-motion remains my favourite technique and I still have lots to learn.

How did your relationship with the NFB get started, and in what respects has it been beneficial to you as an artist?

Producers Alain Corneau (Production de la Chasse-galerie) and Marcel Jean (NFB) were the first to notice my work after Jean Levieriste in 1999. While making The Brainwashers, I developed a relationship of trust with Marcel Jean and quickly felt a sense of belonging to the institution. The NFB is unique in that all levels of production converge under one roof, right down to the filmmakers. This makes for a spirit of community and discussion, which is very stimulating. For me, it was both educational and inspiring. I got to spend time with a ton of talented filmmakers. Today, after 18 years, I still consider it a privilege to be part of the history of the NFB, which continues to maintain a strong auteur culture.

As you now have a fair few films under your belt, what lessons have you learned from your experience making them that you’ve carried forward to how you work today?

With no formal training in animation, I’ve developed very personal ways of going about things. Initially I tried to make my movements look as natural as possible. With little experience building or animating puppets, it was very difficult and I had limited success. That said, there are those who can mask the animation by creating the perfect illusion of movement, but I’m not one of them. On the contrary, I try to reveal the animation, bring it to the fore, justify it. For example, in my film Bydlo, you can just about see the animator’s every move—traces left by the fingers, right up to the fingerprints. This makes the act of animating all the more intimate, human and moving. Each film is a very long process and so for me, this process is just as crucial as the result. From a technical standpoint, making movement utterly believable is very impressive; but I see it as cold and mechanical, a behind-the-scenes job that’s just about the end result. I have nothing against it, but it’s just not my philosophy.

If I remember correctly, earlier experiments in the development of the film were quite different to how it has ended up. Can you talk about some of the different iterations of the idea as it developed?

My initial intentions for this film never changed—though of course, some of my ideas proved unworkable. For example, I wanted to model the body and work directly with the material, as opposed to grafting these elements onto it that would then surface and emerge. In fact, this was my approach at the start of the film when I began engraving directly onto the leg. But I quickly changed tack, since the substance was too solid to be modeled. This example really highlights the limitations imposed by the materials in stop-motion. And then there was the whole aspect of sexuality, an idea I didn’t push as far as I would have liked. The constraint in this case was time. The choices I had to make were often agonizing, but that’s also what kept my creative process fresh. But these are just details, since on the whole, I think I lived up to my original intent, which was to create an experience that was visceral, profound, disturbing and epic.

Why did you decide to settle on using yourself as the main subject?

Well, the original premise was to work on a life-sized body and perform some sort of autopsy. This was an idea I’d had kicking around for some time. But what would I do? What story would I tell? What would I say? I thought about it long and hard and found myself continually up against the same kinds of questions: existential musings from a guy in his 40s with two kids. As I discussed it with my producer, Julie Roy, we realized that my concerns were so personal—that for the film to make any sense whatsoever, I had to look inward. It was logical, then, to have it be a double of myself there on the autopsy table: a subject that would become at once my playground and my battleground.

Do you have a specific process for generating your ideas when it comes to this type of animated work?

Creativity for me is above all a state of mind, particularly with a project like The Subject: an unscripted film, written as it was being shot. When we began, all I knew was how the film would begin and end. But as for getting from A to B, well, there just wasn’t any map. I say this often: an idea has to catch fire for me to really like it. Strangely, this is not so far from the truth. The ideas that give you a burning feeling around the solar plexus are usually the kind that you can’t get out of your head, a bit like an earworm. Above all, it has to be something you connect with emotionally. And when this emotion is strong enough, when the idea is something you can absolutely believe in, then it can set other people alight too.

What sort of labour went into creating such a high-quality duplicate of yourself for the cadaver?

Reproducing my own body involved extensive research: it’s a highly complex and painstaking form of casting. I owe a great deal to my friend Dany Boivin, who also created all the film’s sets. The initial mandate was to produce a carbon copy of my body, which is nothing if not complicated. After weeks and weeks of experimenting, we developed what we felt was the best method for obtaining an optimal result. In the end, the alginate, plaster of Paris and various silicones we used produced a cast of breathtaking accuracy! Pores, fingerprints, fine little lines: it’s all there. Almost to a disturbing degree.

Was the experience of working alongside yourself as a corpse psychologically troubling at all?

That’s a great question. In fact, everything had been set up in the studio and we were ready to go. And then at the very moment when I needed to pick up the scalpel and make that first incision… I just couldn’t do it. The body lay there before me and it was me, my own body, totally naked and vulnerable, even under camera. This threw me into a quandary about the entire project, a difficult phase that lasted close to a month. But then one morning, I had the eureka moment: the idea of having a nail emerge from the foot, suggesting a de-crucifixion. A violent gesture that was nonetheless necessary and very liberating. At that point I knew the real adventure had begun. Oddly enough, it only took a few weeks to completely detach from this representation of myself and see it merely as modeled material.

Were there any other challenges that working on the film threw up for you?

The biggest challenge was filming without a script. I had to invest myself, body and soul, to a degree I’d radically underestimated. The technical demands of stop-motion and the sheer time it takes call for a lot of planning. I had to stay three steps ahead at all times, come up with ideas, arrange the sets for the coming shots, and so on. This meant staying relentlessly creative, and when combined with having to shoot, it could be draining. Though of course, that was how I’d wanted it! Fortunately, there were more ups than downs—something I owe to my amazing team!

All things considered do you feel this is a film about yourself, the human condition in general or something different altogether?

It’s kind of all of those at once; it really depends on the viewer and what they see. For my part, I believe that what I pulled out of myself to make this film exists in each one of us. The questions of being and of the invisible worlds within are difficult to tackle, but they’re intrinsic to each individual. In terms of symbolism, I touched on religion, sexuality and childhood. But every sequence is open to interpretation; it’s how the film is designed. In this sense, the anvil I wrest from the body at the end is something in each of us. We all carry one: our own burden, our own story. 11. The film also seems to incorporate wider themes such as art and politics, were these consciously developed beforehand or were they ideas that came along during production? Most of the ideas for this film emerged as it was being made. But given that by dint of its process, the film was so personal, I think that a great many of its ideas and images already existed somewhere inside my head. At the same time, it’s just as true to say that the ideas, images or concepts were unconscious, with no real awareness on my part of any symbolism. That’s where the film goes beyond me…

To further the previous question, were all of the visual ideas and strands seen in the film planned out/scripted beforehand or was there an element of improvisation as you went?

The pre-production process was developed around a kind of skeleton script onto which ideas could be grafted during the shoot. For all that, removing the anvil was always the film’s pinnacle and central idea. I had a clear vision of this scene even before the project was developed, just as with the very end, where there’s a kind of switch between the two bodies. The rest of the film was inspired by the present moment, by current events, by my discussions, encounters, concerns and so on. The upshot is that The Subject is inhabited more by a certain time period than a script. Which means that if I had to remake the film tomorrow, the result would be totally different.

Looking at the completed product can you identify any themes or concepts incorporated into the film that you weren’t consciously aware of during production?

Since the film’s launch, I’ve received comments of every kind. People come up with references that are social, political, medical, metaphysical, even Biblical, spiritual or prophetic! For example, a woman just e-mailed me this quote from the Bible: “I will remove from you your heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh” (Ezekiel 36:26). Wow! I wasn’t expecting that at all. It really moved me; you don’t need to be a believer to be moved. Basically, it’s fascinating the extent to which I’m rediscovering my own work through the eyes of others. There are so many more examples like that one, and they all confirm the vast number of concepts and ideas that never occurred to me before the film screened at a festival. In that sense, the film has a life of its own, and it continues to surprise me.

As with a lot of pixilation and stop-motion films the sound is crucial and succeeds tremendously here. How hands-on were you with the sound design and general post-production processes?

I’m always as involved as possible in each stage of post-production. It’s extremely important for me, and I love it! As a spare-time musician, I’m particularly interested in and attuned to anything to do with sound. I’ve worked with sound designer Olivier Calvert on each of my films and so have developed this sensitivity to audio, and he and I have also developed a language that makes our collaborations effective and stimulating. This close working relationship has affected every shoot and influenced a great many decisions.

You’ve worked with the film’s producer Julie Roy previously, can you talk about your working relationship and what she brought to the film?

I’ve worked with Julie Roy since I first started at the NFB. She was initially in marketing but climbed the rungs to where she is today, executive producer of the French animation studio. She produced Bydlo as well as The Subject. A key to the success of any film is a strong relationship between filmmaker and producer. I’ve been lucky enough to work with an outstanding producer who’s decisive and takes her projects to heart. Julie is as involved in The Subject as I am. Early on, I remember batting some initial ideas back and forth with her over sushi and a glass of wine. She championed this strange, twisted idea of mine, and it’s above all thanks to her involvement and determination that the film eventually saw the light of day. An autopsy of an inert form, filmed with no script—I mean, what kind of a producer would be willing to take on that risk? Thanks, Julie Roy!

See Le Sujet (The Subject) throughout this week as part of Annecy’s Short Films in Competition 4.

To see more of Patrick Bouchard’s work visit nfb.ca