Oskar Fischinger 1900-1967: Experiments in Cinematic Abstraction

The students in my undergraduate history of animation classes are usually not aware of Oskar Fischinger and his role in the development of abstract animation. However, when I show them one of his films, many make the immediate connection with Fantasia (1940), a film on which Fischinger was fitfully involved in. (He provided designs for the opening sequence, done to Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor, which were not used.) He was a central figure in the development of visual music. He was not the first to make a nonobjective abstract film — the honours seem to go to Walter Ruttmann, a German painter whose first films, starting with Lightplay: Opus 1 (1921), provided the inspiration for Fischinger’s early works. During his career in both Germany and the United States, he would become an effective propagandist for the concept of the “absolute film,” which involved, “the application of acoustical [i.e., musical] laws to optical expression.”

His began his film career in 1922 and during the rest of the decade not only experimented with cinematic abstraction, including Raumlichtkunst (Space Light Art), a sort of multi-screen light show; he also became involved with special effects on live-action movies starting with Fritz Lang’s Women in the Moon (1928). (He also contributed to the effects animation of the Blue Fairy’s wand in Pinocchio (1940)). Fischinger leapt to international attention with his first sound films, including his various 2D studies, as well as the stop-motion Composition in Blue (1935), done in the delightful Gasparcolor process, which he had a hand in developing. The latter brought him a contract with Paramount Pictures in Hollywood, which was fortuitous, as the Nazi Party did not look very kindly on abstract art.

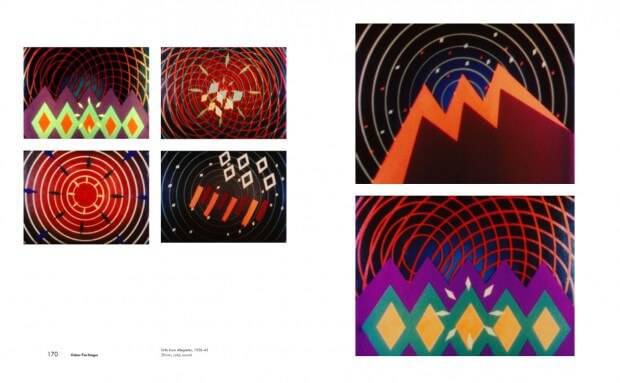

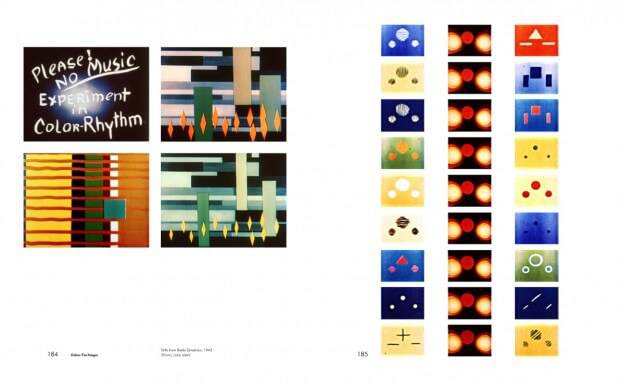

Fischinger’s stay at Paramount was brief and was only able to complete the film he started there, Allegretto (1936-43), the way he wanted to until after he left — it was originally meant to be part of The Big Broadcast of 1937 (1936). He then made the stop-motion short, An Optical Poem (1937), at MGM, and after his stint at Disney, appeared to retreat from work with Hollywood studios (though he did try), struggling to to make his own films as an independent animator; but this period included what many people consider his best film, Motion Painting No. 1 (1947), it was also a period (starting in 1936), when he had began a career as an abstract painter. He did do a few TV commercials, including, strangely enough, one for Muntz TV, a company run by Earl “Madman” Muntz, a huckster who made a fortune as a used-car salesman. Along the way, he experimented with a variety of technologies, including electronic music and 3D stereo filmmaking, as well building his famed Lumigraph, which he characterized as an instrument to create visual music, which he performed with live.

Pages from “Oskar Fischinger 1900-1967: Experiments in Cinematic Abstraction”, showing stills from the film Allegretto (1936-1943)

While his filmography, especially after he fled Germany, was far from extensive; nevertheless, Fischinger had a surprisingly large impact, mostly on other filmmakers and to some extent on experimental composers such as John Cage. His early sound films, such as Study No. 7 (1931), animated to Brahms Hungarian Dance No. 1 (what I like to call one of the national anthems of Hollywood cartoons), inspired experimental filmmakers like Len Lye, Norman McLaren and Mary Ellen Bute; the proliferation of these types of films in the 1930s may be one of the reasons Walt Disney was inspired to include abstract animation in Fantasia. The impact of Fischinger’s films continues to this day, and can be seen in any number of experimental films, music videos and even Michel Gagné’s abstract flavour sequence in Brad Bird’s Ratatouille (2007).

While I never met Fischinger, I did get to know his widow, Elfriede, through my friendship with his biographer, William Moritz, and visited her Laurel Canyon home in Los Angeles from time to time. My knowing her was not that unusual, as she was a fixture in the local and international animation communities, not only promoting her husband’s works and ideas, but also actively seeking to find and encourage new talent, just as Oskar had done.

Pages from “Oskar Fischinger 1900-1967: Experiments in Cinematic Abstraction”, showing stills from the film Radio Dynamics (1942)

Moritz’s Optical Poetry: The Life and Work of Oskar Fischinger (2004) remains the best book on Fischinger. However, Oskar Fischinger 1900-1967: Experiments in Cinematic Abstraction, edited by Cindy Keefer and Jaap Guldemond, published in conjunction with an exhibit at the new EYE Filmmuseum, in Amsterdam (in 2012), in collaboration with the Center for Visual Music, in Los Angeles, is a nice compliment. Something of a scrapbook, it features essays and documents compiled and commissioned by Keefer on various aspects of Fischinger’s career, richly illustrated with stills, photos, documents, letters and preliminary art work For instance, film historian Jean-Michel Bouhours’s “Oskar Fischinger and the European Artistic Context,” explains how “the films of Fischinger [and other German abstract filmmakers] remain strangely absent from … the main avant-garde film theatres in Paris, which was after all the hub of global cinephilia.” Musicologist Richard H. Brown’s “The Spirit inside Each Object: John Cage & Oskar Fischinger,” explores the brief relationship between the two which had a strong impact on Cage, especially after he helped out on An Optical Poem. Independent artist Paul Hertz writes on “Fischinger Misconstrued: Visual Music Does Not Equal Synesthesia,” is a useful antidote to a popular misconception regarding abstract films. In addition to these and other original essays, there are some historical interviews with and statements by Fischinger, testimonials from various filmmakers and historians, a filmography and a chronology of his German period, along with a bibliography.

As in any anthology of this sort, the writing ranges from the accessible to the more academic in tone. It is book to sample and savour at one’s leisure and is especially recommended to those interested in visual music and motion graphics. If I have a complaint, it is i lack of an index (which is much more bothersome in the Moritz book).

P.S.: For these interested, The Center for Visual Music’s official Fischinger research site is at www.centerforvisualmusic.org/Fischinger, while the Fischinger Trust’s site is www.oskarfischinger.org

Items mentioned in this article: