More Oddness from Oddworld with release of “Stranger’s Wrath”

Skwigly ventures into the strange and unknown, looking at the Oddworld cinematic from the new game ‘Stranger’s Wrath’

We’re all odd, and we’re all strangers, aren’t we? Or, given that oddness and strangeness are often the same thing, it’s not surprising that California-based animation and game studio Oddworld Inhabitants would come up with ‘Stranger’s Wrath’, released on January 26, 2005. Featuring a high-resolution cinematic introduction, ‘Stranger’s Wrath’ is an impressive addition to the interactive, virtual-world environment, story-based situational 3D-CGI animated video game genre. The process behind the company’s creation of the game is the story-within-a-story – something that tells us more about the current state of the animated arts than its plotline featuring non-real heroes working as bounty hunters in bizarre and dangerous imaginary realms.

Before a single pixel is animated, game designers need a concept, story, or premise that sets everything else into motion. Oddworld Inhabitants president and creative director Lorne Lanning said work on ‘Stranger’s Wrath’ began three years ago. They had a lot to live up to, with previous games like ‘Abe’s Oddysee’, ‘Abe’s Exodus’ and ‘Munch’s Oddysee’ earning prestigious industry awards and legions of fans. With ‘SW’, they wanted to introduce new and innovative game play mechanics, with first and third-person encounters in-vast regions of dust, forests, mountains, industrial settings, and snow and ice. The game was planned to include a new roll-call of colorful and maybe slightly nasty characters, and would be a departure for the company.

So, of course, the odder the better as far as the story or premise was concerned. The Angry Unknown-Person of the title, or ‘Stranger’, is a lone bounty hunter. Bounty hunters make great dramatic leads, because they’re fighting crime, they’re sleazy and outside the law themselves, and of course they have to get violent occasionally and use all kinds of weapons, and so on. With this guy, the weapon of choice involves a wristmounted, double-barrel crossbow loaded not with traditional arrows, but with various ‘critters’ the Stranger hunts down and then employs as ammo, or ‘live ammunition’. You have to admit, this is a bit odd. The Stranger’s goal is to bag bounties, and earn enough of whatever passes for money in this world to pay for a needed and mysterious medical procedure. So not only is he odd, he’s sick, but that’s to be expected.

Play gets more and more dangerous and dramatic, until our hero is forced to hunt the ‘ultimate bounty’ (whatever that may be).

There’s a lot more here. Although we don’t quite know what the Stranger’s species actually is, we do know that the Clakkerz (settlers), the native Grubbs, the Outlaws, and the Wolvarks (security guards for the Sekto Springs Bottled Water Company) all more or less co-exist in a place called the Mongo Valley, with all its dust, forests, and so on. It’s all happening on the same continent as the other games, and a sense of humor here is essential.

“I have to say that the violence that does occur in the game is very similar to our previous games, with the ability to squash, blast, and chop the bad guys up in a really entertaining way,” said Oddworld president Lanning. “The live ammo allowed us to make a game that was more a strategic ‘shoot-out’ than a shooter. I think these qualities have given all of our games the ability to appeal to a very wide age range, from six to seventy-six, but officially we have a teen rating.”

So much for story. But how does the game actually play, and what techniques were used to create the action and the cinematic? Lanning said in ‘first-person mode’ the movement of the character is more “platform-like”, with low speed, a short turn radius, and two types of ammo for your crossbow.

In ‘third-person mode’ you get a 360-degree punch, a devastating head-butt, and speed-running like a motorcycle at a real-world rate of about 55 miles per hour.

“It was very important for these mechanics to correlate with the storyline and game play, and I think we were successful in achieving that,” Lanning said.

The Oddworld company has two different departments for game design and programming. “We have an awesome programming team who built the entire engine from scratch, and we really did everything we could to push the hardware capabilities of the Xbox,” Lanning added.

The visual treat that tempts gamers into the action is the cinematic that opens and closes play. Lanning said there is a total of 13 minutes of CG animation in the game.

They wanted a fast-paced opening, with interesting visuals that set up the story well. “It opens with the Stranger being chased by an Outlaw, then turning the tables on him, trapping him, and turning him in for payout,” said Lanning. “This sets the stage for the first level. As game play progresses, cinematic sequences move the story along to the ‘Vykker’ surgeon’s office, where the Stranger’s medical issue is revealed, and on to the bounty store where he receives the ultimate of bounties that could easily cover the costs of his medical procedures, then to his run-in with a mean group of Outlaws, and ultimately to the final resolution of the game.”

“The concept of a chase worked well for us in a number of aspects,” said Technical Director Iain Morton. “The first half of the movie involved no dialogue whatsoever, allowing me to set up the facial for the characters during the process and have them ready in time for the later shots where there was some dialogue.”

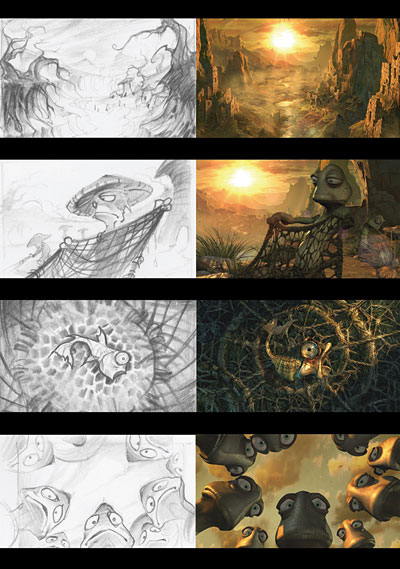

Two production designers and two animators created the CGI for ‘SW’. The cinematic ‘pipeline’ is modeled on that of a feature film, and starts with character design, a script, and then production. Technical director Morton said the script is first translated into a story-board, and a story-board animatic is created with rough sound. Pacing is fine-tuned, and there’s a considerable amount of tweaking. “Once the animation is close to final, the characters are rendered with high resolution, grey-shaded geometry to check deformations on the model,”

Morton said. “The lighting, final models and effects are then rendered out and the final shot is composited.”

Morton also said that key movements in the cinematic are sketched out and visually described early on, and Photoshop renderings are used for environments, to show what modelling, texturing and lighting would work best.

Senior Animator Rich McKain said a lot of changes were made to the ‘rig’ for Stranger, including controls for individual finger digits, more eyebrow and mouth controls, and squash and stretch controls for arms, legs and body.

“For a long time at Oddworld Inhabitants, throughout the development of Munch, all the facial animation was done in a completely different file than the body animation. Only after they were both completed and rendered would you see the facial and body animation together,” said McKain. “I still can’t believe they animated that way for so long.”

The so-called ‘CG pipeline’ called for a high degree of organization and production efficiency from the Oddworld team. Morton said they needed to work in “a very linear way”, with each piece of the puzzle completed one at a time, and keeping scheduling very tight so that artists were not wasting time waiting for someone else to complete their part. Low-resolution characters and environments had to be ready early for CG animatics to begin. “Any spare time would be spent light rendering and compositing the backlog of nearly completed shots to get the lighting and effects blocked in and closer to final render,” Morton commented. “We had to be really honest of our limitations with production design.” Rendering for the project was done using Maya render, and compositing was done in Shake. The CG department at Oddworld has the luxury of a ‘dedicated render farm’ of more than 30 processors, McKain said.

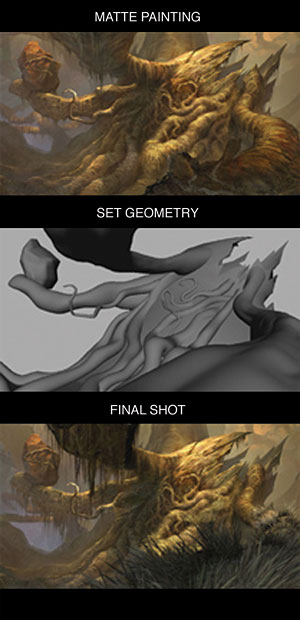

“The basic approach I followed when putting a shot together on this project was always the same,” he said. “In the case of a shot using a matte painting as a background, the painting would be underway by the time I began the final lighting and texturing of the scene, and I would set up the comp as one of my first steps. Even though the matte painting was often only rendered in the comp, I would place it in the 3-D scene in

Maya on a card in the correct position and use it as lighting and texture reference as I worked on the shot.”

He went on to explain that rough animation would be merged onto the high resolution characters early to test lighting from angles used in the final shot. In early stages of lighting, key frames were rendered at low resolution and built into composites, to check levels, reads, color and contrast.

“Another formula that seemed to work well was to create a list of effects passes that could be added to every appropriate shot as a final step to add life and coherence throughout the movie,” he said. “Dry grass, flies and dead leaves seemed to suit the dry, decaying environments we were creating, and they were a step in the process of almost every shot.”

Tools programmer Rob Tesdahl created many of the effects throughout the movie, including the dynamic leaves and flies.

More traditional illustration techniques were also used. Darkening and cooling the edges of the frame subtly draws the eye to the centre of the action, for example, and keying out or blurring the highlights of a frame added a soft glow, like a lens filter.

The addition of a lens flare would tie layers together and add realism. Colour correctionwas also used.

“All of these things were generally added to each composite as a quick and easy addition,” McKain said. “Having a formula in mind when starting to build a shot helped speed the process along, as well as add consistency to the movie.”