Interview with Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre (‘Oscar’)

UPDATE: As of 30/06/2017 Oscar is now available to watch in full (click here or stream below)

Following a string of successful and visually inventive approaches to the animated documentary in the form of the short films McLaren’s Negatives (2006), Passages (2008), The Sapporo Project (2010), Femelles (2012), Flocons (2014) and Jutra (2014), Montreal-based filmmaker Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre has this year released her latest project Oscar. The film, an exploration of the life of legendary Canadian jazz pianist Oscar Peterson, extrapolating poignant musings and reflections from existing interviews through a variety of animation approaches, is co-produced by MJSTP Films (Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre/Jocelyne Perrier) and the National Film Board of Canada (Marc Bertrand), in collaboration with Télé-Québec. Having already picked up an Audience Choice Award at the New York City Short Film Festival, Oscar has since screened at the 15th edition of Sommets du cinéma d’animation in Montreal and the 2017 REGARD Festival in Saguenay.

When did your interest in Oscar Peterson begin, and what was it about him that determined he be the subject of your film?

I got really interested in Oscar Peterson’s music while I was working on McLaren’s Negatives, an animated documentary film on Norman McLaren that I produced and directed in 2006. My favourite film of McLaren’s has always been Begone Dull Care (1949), a short that was co-directed with Evelyn Lambart.

While making McLaren’s Negatives, I discovered that the music in Begone Dull Care was an original score from the Oscar Peterson Trio. I liked it so much that I bought a couple of Oscar Peterson’s albums. The more I discovered his music, the more I was hypnotized by his extraordinary talent. He is a brilliant musician with a unique approach to jazz piano. I got hooked on his music.

Like I envision the work of other artists I made films about, such as Norman McLaren or Claude Jutra, I aim to educate the audiences about Oscar Peterson’s legacy. Therefore, my main objective is to use animated documentary in a way that presents the subject in an innovative way. We live in an era when people can easily read biographies or google a person on the Internet. Therefore, with animation, the objective is to add an additional layer of narrative within the documentary portrait. The short film presents something you could not know about the subject without watching my animation. I do not aim to reproduce biographical information through my filmmaking. I want to go beyond the scene, inside the protagonist’s brain, and recreate a particular aspect of his life.

Having previously tackled prominent visual artists such as Norman McLaren and Claude Jutra, did having the focus of this film be a musician present any challenges to your proces?

Yes, music licensing for this film was quite an ordeal, for sure. In order to use Oscar Peterson’s music in my film, I had to clear the rights of the composer, the musicians, and the publisher. Kelly Peterson, Oscar Peterson’s widow (who gave me permission to make the film), suggested that we only use scores that were Oscar’s originals. This was such a great idea! Not only did it make the licensing a little easier, but also having only Oscar’s music depicts his musical spirit in a better way. I also have to say that I had a lot of help from the National Film Board in going through all these agreements with big companies such as Universal and Sony. We were hoping to be able to afford all the music with the help of Kelly Peterson, because the first steps of the negotiation were out of our price range.

Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre (Photo ©Lou Cognée)

How did you come upon the source of the primary interview, and why was this footage essentially chosen as the foundation on which the rest of the film is built?

Kelly Peterson put me in contact with Hoda Elatawi from GPAC Entertainment Inc. who made the film Oscar Peterson: Keeping the Groove Alive (2003) for the CBC. I contacted her and told her about the portrait I wanted to make. She was so helpful and generous; she allowed me to transfer all the rushes she had archived for the feature. I ended up with over two hours of interviews with Oscar Peterson. These interviews were done four years before Oscar’s death. I decided to use them, mainly because he is offering a reflection about the life he had, and I thought it was really touching to see him open up so much about his personal life. As I said earlier, we can easily access his music and find his great musical achievements, but a reflection about his personal life is much harder to find.

How did you go about sourcing the additional archival material used in the film?

Oscar Peterson is a very well-documented figure but the problem, in the long run, always comes down to the clearance of the rights. This was a co-production with the NFB, which is a government institution, so it has to be by the book and it rigorously goes through any licensing agreement for visual or musical material. So, as a director, you need to make choices in terms of rights clearance. Is it really worth spending an incredible amount of time tracking a person? Is it a good idea to spend a large amount of money on a particular archive? Being the producer as well as the director, I always need to also think in terms of costs. Some photographs in the film were up to $500 apiece since they were coming from well-known photo banks such as Gettty Images or Corbis. On the other hand, we were able to recreate a part of the city with photographic material from the City of Montreal archives. These were $5 apiece. It is really a matter of compromise and choosing what is really worth fighting for. The good thing about being the producer as well as the director is that the director always has the last word.

Oscar (©2016 NFB/MJSTP Films Inc)

Of course the music itself has a vital role to play in the film. How did you go about selecting pieces and working out the creative interplay between sound and visuals?

Music is there to emphasize the mood of a section, without guiding the spectator to feel a precise emotion. It gives movement from one part to another and helps with the continuity and general unity of the film. I see music as a character in the film that translates Oscar Peterson’s emotions. As Oscar says in the film: “My music? I would say emotional, because I play exactly the way I feel.”

One of the main focuses of the piece seemed to be on personal woes and loneliness. Why were you keen on exploring this side of Peterson?

I always tend to project myself into my animations; my life and preoccupations at the time of the production somewhat intertwine with the subject of my films. I need to feel a close connection to my subject in order to sustain the process of animation documentary filmmaking. Of course, I was totally in love with Oscar Peterson’s musical universe from the get-go, but I needed to connect with him on a more personal level. I was quite touched by the fact that he regretted missing out on his family when his kids were young and wished he hadn’t got married before the age of 40. Things were quite hard for him; he was torn by choosing his career over his personal life and was especially lonely. On the personal front, I separated from the father of my three daughters while I was making this film, as he decided to live and work in the United States. I think the difficulties of my personal life, the dissolution of my family, correlated with those Oscar Peterson encountered as a travelling musician and became a solid piece of artistic inspiration for me, and I went for that direction. People have this vision of the greatness of the lives of mythical figures when in fact many of them are quite lonely and sad.

What was your main process for generating the animated visuals?

Mixed media? I never reveal the recipes for my films….

You’ve been producing excellent work as MJSTP Films for some years now. Were there any new areas or animation processes in this film that hadn’t been explored before?

I would say this film is the one that uses the most digital technologies and 3D principles—more than any of my other films. While this can speed up the process, I also realize it can at the same time slow it down, as it is hard to make sure the computer is not totally imprinted in the images and the narrative. It is important for me that the animation process and the technique do not affect the viewer’s experience while they are watching the film. I was quite lucky to work with Ehsan Gharib, who is an After Effects magician, and the talented Brigitte Archambault.

Having previously made a film with Claude Jutra as its subject (albeit posthumously), and with yourself being a recipient of the Jutra award, how did you react to the revelations of abuse that surfaced earlier this year (and the subsequent controversy of his name being immediately disassociated with Canadian film culture)?

I was totally, I mean absolutely, devastated.… We all were. It is hard to put into words the way you feel when you spend so many years of your life making a portrait about someone and then you realize you did not really know him after all. The revelation that he was a pedophile is impossible for me to accept and forgive, especially being a mother of three young daughters. On the other hand, I was distraught at the way people around me reacted. The community rejected him strongly; he was erased from public spaces within 24 hours. I think the decisions were based on an emotional reaction rather than a rational one. Claude Jutra is a legendary figure in the Quebec filmmaking landscape: the community identified strongly with him. They felt betrayed; I think we all did. But erasing him from the face of the earth, from filmmaking memory and from history, does not resolve anything or make our children safer. We need to dissociate the man from his work. I hope with time, when the initial shock has passed, people will be able to look at his films as the great works of art they are. In my opinion, the saddest part is that he was not there to talk about it. He was deemed guilty without a fair trial. He had the worst week of his life while dead. It is a truly sad story from all angles: the victims, the community, and the filmmaker’s legacy.

Can you tell us a bit about your upcoming film Your Mother’s a Thief?

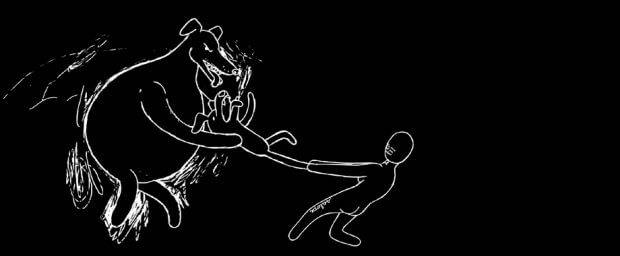

Ta mère est une voleuse! (In production) ©MJSTP Films Inc.

This will be my first animated fiction film, and the subject is parental alienation. A couple separates but they cannot place their child first; therefore one of them is alienating the child from the other parent to get revenge. For the visual style, I am going with simple white line drawings on black backgrounds like in Passages (2008), and using a lot of scratches and experimental stroboscopic images like in Flocons (2014). The combination of both will emphasize the characters’ emotions and actions. Antoine Bareil is scoring original music that will truly add another layer of narrative to the animation. Brigitte Archambault, my collaborator on all my other films, is on the animation. It is a very low-budget, homemade animated film that is universal. Hopefully this taboo subject will touch people all around the world.

Oscar will screen as part of the Sommets du cinéma d’animation programme Animating Reality 1: Familiar Faces, taking place on Thursday November 24th and Sunday November 27th.

For more on the work of Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre visit mjstpfilms.com