Q&A with Michèle Cournoyer, director of ‘The Hat’ and ‘Soif’

(Image provided by the NFB)

Jutra Award-winning experimental director Michèle Cournoyer’s career in film began in 1972 working on scripts, sets and costumes for filmmakers such as Mireille Dansereau and Gilles Carle. Following a series of independent, Dadaist personal short films in the 80s, Michèle’s work soon became known to the NFB, leading to their first production A Feather Tale in 1992, which was brought to life through textural rotoscoping. Her style has evolved over the years into an identifiably stark, metamorphic ink-on-paper aesthetic, and over the course of her collaborative work with the NFB she has continued to produce thought-provoking, no-holds-barred work using animation as a communication tool for such social issues as terrorism, sexuality, incest and, in the case of her most recent short Soif, alcoholism. The film, which was co-produced by Unité centrale (Marcel Jean and Galilé Marion-Gauvin) and the NFB (René Chénier), is described as “a tragedy in five acts centered on a woman who must confront the fate of her existence” and recently received an Honorable Mention for Best Canadian Short at this year’s Ottawa International Animation Festival. Her other work, including The Hat (1999), Accordion (2004) and Robes of War (2008) have also received much major festival success, winning awards at Annecy, Zagreb, Hiroshima, Vienna amongst others, as well as being the subject or literary analysis in Jayne Pilling’s recent book Animating The Unconscious. Michèle took the time to share some insight into her career and working process with Skwigly.

Could you tell us a little about your background prior to filmmaking?

I was born an artist in an artistic environment. I drew anywhere and everywhere… in school books—you name it—mostly portraits. Later, I became a film costume designer and decorator after studying fine arts in etching, painting and sculpture. My first animation was painted on four sculptures of a woman holding in her arms a baby that becomes a bouquet of flowers. A scholarship then took me to London during the Swinging London era, to Hornsey College of Art, for a postgraduate degree in graphic design. And my silkscreen images increasingly became sequences.

Then one day I saw a man with a baby in his arms. [I had] my first real cinematic vision in the style of the Dadaists and the Surrealists: the baby transformed into a bouquet of flowers (it was the era of flower power). A professor at the school organized a live photo shoot with the man and the baby. Then, I painted and animated the coloured flowers to the music of Éric Satie’s La belle excentrique. My first animated film was born.

From what I gather your involvement with the NFB began with Cinéaste recherché (filmmaker wanted), a scheme which is still active for new filmmakers today. How did you come to know of it initially and what effect did it have on you creatively?

For A Feather Tale (La Basse-cour), I was doing tests with the NFB’s vertical animation camera, but independently. Then I saw an ad in a newspaper announcing the Cinéaste recherché contest. I asked Yves Leduc, who was the director of the NFB’s French Animation Studio at the time, if I was eligible. Winning the competition allowed me to make my first animated film professionally, surrounded by seasoned filmmakers and cameramen; to do a real film shoot in a real studio and to draw using rotoscoping, in ideal conditions and with complete creative freedom, without any financial constraints. A door was opened. I held a permanent position as a director at the animation studio for several years.

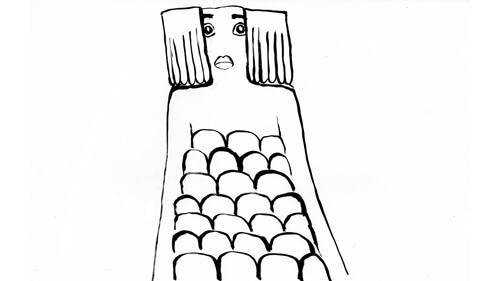

Soif (Michèle Cournoyer/NFB)

You’ve worked with fellow filmmaker Pierre Hébert in the past, someone who also deals with strong themes married with atypical approaches to animation. Was this experience beneficial to you as animator?

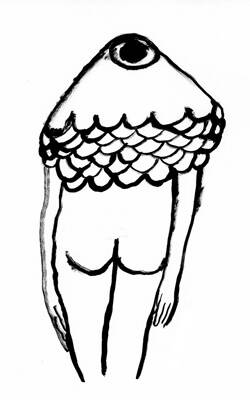

Pierre Hébert deplored that with computer-assisted animation, the body tended to disappear during the artistic process. For the film The Hat, I had begun working in a very heavy and overly realistic manner with aesthetic and artificial digitized images; I couldn’t seem to find the movie in such intimate subject matter. I wanted to destroy the computer. Pierre became studio manager and my producer. He encouraged me to start over from scratch. He took the computer out of my office and said: “Draw by hand… Don’t censor yourself; work without a net.” For the first time, I was animating ink directly on paper. Little by little, I developed a real, more physical relationship with animation. Mastering the technique took a while. I relied on my unconscious. Pierre guided me throughout the entire process and helped me clarify the narrative intent.

Having worked in both traditional and digital animation, do you find that you feel more at home with one than the other? What would you say your ideal animation medium would be?

For the film An Artist, I became enchanted with new technologies like digital rotoscoping. With The Hat, I reconnected with traditional ink on paper drawings. I rotoscoped myself mentally, in my head. I used myself as a live model. Once I’ve put myself in the scene, I do what’s called autofiction. It’s more direct; there’s no intermediary. I become all the characters in my drawings. I dig deep into my emotions and personal experiences. When I draw by hand, I sense an intimate relationship between the ink, the paper and the story that’s brewing inside me. Soif is my fourth film made with ink on paper.

The Hat deals with the internal pain of a female exotic dancer, who perseveres (through strength or, possible denial?) despite her past traumas having a firm, hold on her. Is this perseverance of spirit an important component of the portrayal?

The body of the stripper is anesthetized because sometimes, a woman who has suffered incest no longer feels anything. She is in denial. Then it takes one element, a fixation on an object from the past, to bring the emotion back to the surface. This can take years. The sight of the men’s hats in the bar triggers the painful childhood memory of the man in the hat.

The Hat by Michèle Cournoyer, National Film Board of Canada

A lot of your work deals with both human strengths and human weaknesses. Overall is it your intent to focus on one more than the other?

My world revolves around the human condition, with all its strengths and weaknesses.

Your film Accordion dealt with the marriage of sexual relationships and technology, a subject that has become more societally prevalent in the decade since its completion. Have your attitudes toward this subject changed at all since you originally made the film?

I would make the same film about love online, about the inability to communicate. In today’s age of social networks, the ending might be different, however.

How have you found audiences/critics to be when faced with such direct subject matter?

The film Accordion was selected to be in competition at the Cannes Film Festival, which I attended. After the screening, to me it felt like the inability to communicate projected by the film had spread throughout the room.

In Montreal in 2004, journalist Marco Deblois wrote an article that appeared in the Quebec film magazine 24 images.– “There are no words to describe this animated film without words, text or dialogue. For the viewer, it’s like diving into the unspoken, the unspeakable, into a pool of poisoned water…”

As regards your creative process, are visual ideas plotted out beforehand or do you approach the work entirely as a stream-of-consciousness affair?

Inspiration begins with a physical vision that becomes an obsession, and then a film subject. I use my brush to create the initial storyboard that depicts the subject of the film. There is a kind of back and forth between writing, animation and editing. It all happens a little at the same time.

It’s been quite a few years between your previous film Robes of War and Soif. Did anything in particular prompt your return to animated filmmaking?

For the Quebec film magazine 24 images, Marcel Jean had invited several filmmakers, including myself, to illustrate the theme of “Love of Cinema.”

I drew a woman who transformed into a movie theatre. Her body was covered in seats; her arms were the aisles on either side. Her hair consisted of the closed curtains. I opened the curtains to reveal her face, her mouth.

Then with a brush, I wrote a screenplay. The woman performs and appears in her own film. The ink becomes alcohol. I was obviously thinking about my storyboard on alcohol entitled SWAF, which I co-wrote with Claude Jutra in 1984. It’s the story of a man who drinks his life away.

Soif is no longer the same project in 2014: the main character is now a woman who drinks the film’s sole spectator: the man of her life… alcohol.

What, more than anything, do you hope audiences will take from Soif?

I don’t have any set expectations of what the audience will feel.

It’s a surprise every time.

To see more of Michèle Cournoyer’s filmography you can visit her NFB page. Soif (Thirst) will screen at this year’s London International Animation Festival in the programme Looking For Answers, 7pm October 24th.