Interview with Matthew Rankin (‘The Tesla World Light’)

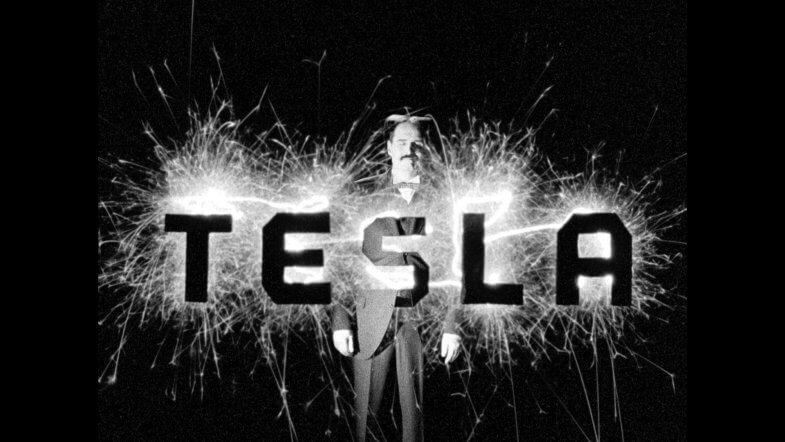

Presently based in Montreal and originally hailing from Winnipeg, Manitoba, Matthew Rankin’s work often combines factual elements with an experimental approach. This year he has released The Tesla World Light, a remarkable tribute to Nikola Tesla, documenting a troubled period of the renowned inventor’s life through a combination of exquisitely performed pixilation and experimental filmmaking techniques. Produced by Julie Roy at the National Film Board of Canada, the film is set in New York in the early 20th century and takes its inspiration from real events (in which renowned inventor and pigeon-admirer Nikola Tesla makes an appeal to his previous benefactor J.P. Morgan). With roots in both documentary filmmaking and the avant-garde, the film also boasts sound design by Sacha A. Ratcliffe and is Matthew’s second to be made at the NFB, following 2015’s The Radical Expeditions of Walter Boudreau.

Following the film’s premiere at Cannes International Critics’ Week back in May, The Tesla World Light has since screened at the Annecy International Animated Film Festival and the Sydney Film Festival, with upcoming screenings at the Toronto International Film Festival and the Ottawa International Animation Festival this month.

Can you tell us a bit about your various creative paths have converged to the point of creating the type of work you’re known for now?

I grew up in a city in central Canada, it’s the geographic centre of North America in fact, called Winnipeg. As a teenager I started to do animation, I worked for Sesame Street for a few years, propagandistic animated pieces about the letter A and elbows and stuff. I was sort of involved in the independent film community in Winnipeg, then I went to university in Quebec, I studied history and while I was studying I continued to make films and to draw and at a certain point I just came to the conclusion that, I wasn’t going to be an academic, I had to commit to art-making. So for the last ten years I’ve just been doing art, full-time.

So what was the initial inspiration to go into studying history for a while?

I’m interested in lots of stuff and I think when you are doing creative work you want to feed it, so I had a lot of questions and I wanted to explore those and step away, step back. I guess subconsciously that’s what I was doing.

Primarily, now that you make films with animation in them, would you call yourself an animator or is what you do as a filmmaker kind of a broader thing?

I do think of myself as a hybrid filmmaker, all of my work is hybrid genre, hybrid form,. hybrid storytelling so I think of myself in that way. Though animation has become more and more a part of my work and I also like the world of animation because it’s a little bit closer to fine art, and I feel closer to fine art as a filmmaker as well. In the world of fiction films, drama, the concern for the image is not the same, the focus is usually elsewhere. But I have a lot of concern for images so I feel close to animators for that reason, because I share that with them.

The historical element is quite prominent in your films, it does seem as though each of the films – certainly the recent films – have this foothold in a historical event or a historical figure and then they spin out from that. Are they predominantly fictional works based on non-fiction or do you consider them kind of non-fictional interpretations of events (as in a type of documentary filmmaking)?

You could consider them that way, they’re kind of hybrid, they sort of walk between those worlds, from a point of realism to something much more ecstatic to the point of abstraction, that’s sort of what I like, is to start with some sort of event, some sort of character and take it to the point of absolute surrealism. I think that history is kind of the fount of my inspiration, it’s where I reflect, it’s where I represent, it’s the world in which I comment. The idea is always to make cinematic emotions, and I think that there are certain things that cinema can do that history, for example, cannot, or when you’re trying to represent a very credible account of the past that is historically accurate and historically true and factual, inevitably at a certain point you fail, because the transformation to cinema is necessarily an artistic and fictional process, so I don’t even try to make the claim that I’m representing the past in an authoritative way, I’m taking it absolutely into abstraction. And there’s so much of our lives that is abstract, there’s so much about the human experience over history that is abstract. This film is about his nervous breakdown in 1905 and to me that is abstract, the feelings that fill one at a point of nervous breakdown are abstract feelings, and you can’t even attempt to empirically demonstrate those in any truly accurate way, it has to be imaginative. So the idea is to take it all the way, to that point.

That brings me to why this figure was so interesting to you, to make a film about?

It’s a few things. One of the reasons for that is formal, visual, in that I was doing two experiments. I was painting on celluloid a lot and I was using a kind of India ink that, when it would dry, would crackle quite spectacularly in all directions. It looked very electric, and I thought I should do something with that. Then, parallel to that, I was really interested in the Japanese filmmaker Takashi Ito who did some experiments with light painting that I thought were really interesting. Then I saw these photographs Tesla had taken of himself where he’s reading a book in his laboratory, and there are thunderbolts firing all around. It’s very dramatic and a little absurd as an image; it is a double exposure, he wasn’t actually surrounded by electricity, but his choice to represent him tranquilly reading while fire is bursting all around him I thought was very flamboyant with a sense of the absurd. Also it struck me that this was essentially light painting, a long-exposure of his electrical receptor and generator, that was how the electricity was photographed. So that made me think of Takashi Ito and this painting I was doing on the celluloid and the idea of using light as the raw material of animation. It struck me that I’d never really seen a really ambitious light-painting animation piece, and I thought Tesla was the perfect subject to make one with. Of course I’d always admired Tesla, I was very interested him and this point in his life in 1905 when he breaks down in discouragement was also interesting to me, because I think of him almost as an avant garde artist in a way. He’s doing all this work that people don’t quite understand, it’s abstract and he’s sort of going nuts trying to get it done. So all of that was very exciting to me.

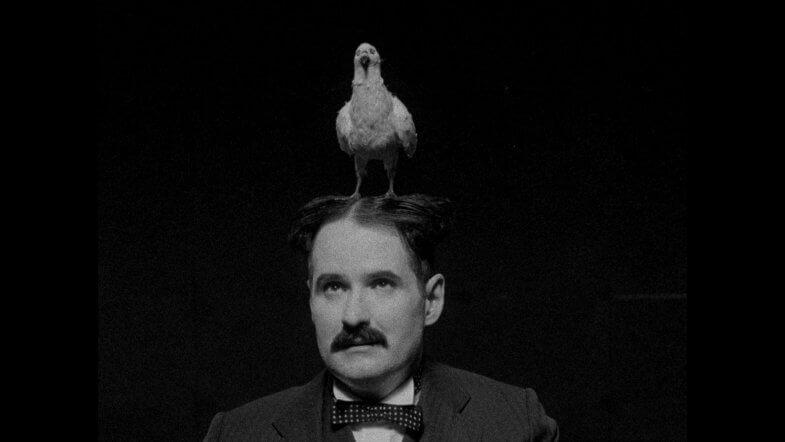

You mention the absurdist element of the imagery – there is an element of humour to the film in the relationship between man and bird, where that comes from and what it leads to. Was that important for the film, to balance out the more serious elements?

Yeah, I guess that’s true. I think the film has something of a comic tone to it but there aren’t really ‘jokes’. That’s sort of the tone I wanted, again this image of Tesla reading the book with lightning around him, it’s absurd but not exactly ‘funny’, you wouldn’t look at it and laugh, but there is a note of irony to it. That happens even if I don’t attempt to do it, it’s sort of how I see things. I feel like in all of my work I walk a fine line between irony and earnestness, between utopian longing and slapstick, so there’s always a little bit of that.

When it comes to the bird, I got really excited about it because it reminded me of my own relationship so much. At a certain point I stopped thinking about the man/bird ‘romance’ and got into it quite earnestly. I met some pigeon fanciers while researching the film – they’re sort of a dying breed but they’re really interesting people who live with pigeons. They all told me that there’s a certain kind of acceptance that birds have for humans that they don’t feel with humanity at large. That was meaningful to me.

What was the process of casting the actor like? Was it hard to find someone who’d fit the role?

No, that was another factor in making this film was that I knew exactly who I wanted to play Tesla. It’s my friend Robert Vilar who’s a great actor in Winnipeg I’ve worked with a lot. We did this little test where his hair went in this triangular shape, that was enough to know everything was gonna work, that he was the right person for it. He’s a very patient, thoughtful actor and very good at acting in stop-motion, which is not easy. He spent days with us making slight micro-adjustments to his body, it’s very demanding but he did it very exactingly.

Something that did strike me was that the pixilation in the film was, at times, very naturalistic while retaining that animated look, which I imagine is very hard to pull off. It’s a nice overall effect.

That is a testament to Robert’s power, because there’s a tendency to overcompensate in stop-motion. I’ve made a few films where people have to do stop-motion acting and it’s not easy, not only to move but to build an emotional arc to the way one moves over the course of many hours of micro-adjustments. A Winnipeg animator friend of mine has made a lot of films with Rob as well, so he’s had a lot of practice which is unusual for an actor, to practice moving frame-by-frame so much.

Some of the other elements of the film it would be nice to hear how they came about, you mentioned that manipulating film and light experiments were part of it. Was it all meticulously worked out, shot by shot, what would be required?

Yes it was, it was shot on 16mm and all of the light painting of course is very mathematical and has to be calculated very precisely so it doesn’t screw up the exposure if you get it wrong. My photographer Julien Fontaine is a great mathematical genius and he figured this all out, so all of the exposures were really beautiful. It’s often four or five exposures for each frame, we had to open the shutter and, working in complete darkness, we had to flash a light on the actor very quickly to expose him, flash the décor, the set, to expose that, and then I, dressed completely in black wearing a balaclava, would light a sparkler and drag it artistically through the frame, and then we would close the exposure. Then we’d move Rob and do it again! I think we burned something like 15,000 sparklers over the course of the film. So some of them were like that, freestyle with me painting in the air, and there were others where the Art Director Dany Boivin and myself built a few rigs to create specific forms. For example when Tesla is sitting in front of his coil it’s one of the images in the film where you see him in silhouette and there are these coils of light behind him, that was created by building this long arm that was attached to a kind of windmill we would turn. So each frame we would change the position of the lights, open the shutter and turn it to create these perfect rings of light. We also built these fireballs, spheres, they were created from this ring with a light affixed to it that we’d spin and turn on its axis, back and forth, and that creates a kind of 3D fireball of light. So there were little tricks that we’d figured out.

Did you use reference footage to get a sense of how light and electricity behaves when you were doing these approaches or was it more of an artistically abstract approach?

The idea was to make it more abstract, it was also about the motion itself to some degree. There’s one section where the idea is just chaos, an electric nightmare. Then for some of it it’s much more controlled, because electricity is like that – it’s utterly chaotic but there are ways of controlling it. It’s strange and mysterious and mystical, even Tesla, who devoted his entire life to electricity didn’t understand exactly why it exists. So that was the idea, sort of a metaphoric electricity really, rather than absolute realism.

Tesla remains a very prominent figure for the work he’s done, with museums and societies still very much active today. Did any of these have any involvement or consultation when it came to this film?

Not really. There are a whole bunch of conspiracy theorists who I find quite interesting. There are a few books written, including by a Québécois scientist who wrote all this really strange literature about how Tesla was from Venus and who wanted him to finish his work via interplanetary communications. I was reading these mainly for my own pleasure but also the mysticism around Tesla I found really interesting. A few people have this very mystical relationship with him, his fans adulate him and he is a mysterious figure, in many respects. But no, I didn’t really consult with Tesla specialists – of course I read a lot, but I didn’t consult any of the societies. I went to the Tesla Museum in Belgrade which is wonderful, and I visited pigeon fanciers to get closer to that. It’s true that there are a whole host of Tesla societies but I didn’t speak with them.

Usually museums or societies enjoy and celebrate the cultural legacy of their subjects. Do you think the film, now that it’s done and out there in the world, might be of interest to some of them?

I don’t know, a big inspiration for me on this project was the Philip Glass/Robert Wilson collaboration Einstein on the Beach, which I always really liked, it’s a great, abstract biopic, you take the life of someone and strip it down to its most abstract centre. So that was a big inspiration, I’m not sure how the Einstein people reacted to that when it came out…so I’m not sure. It is sort of an abstract, experimental film, it has this narrative element to it but I don’t know how the Tesla people would respond to it. I do know they are very concerned with Tesla’s legacy being better understood by the world, which is a very important undertaking; this film is more abstract than that, there’s no specific propagandist agenda to it. But I’d love to show it to them, of course.

Do you have anything on the boil that you can talk about?

I just finished shooting a feature-length motion picture entertainment which is slightly animated, but mainly live-action. It’s also historical, it’s sort of a pseudo-biopic of a Canadian politician in the late 19th century who fell in love with a shoe. He was a real person, William Mackenzie King, he was the Prime Minister of Canada during the wa. We just finished it a few weeks ago and I’m now editing it.

It’s interesting, the objectophilia relationship there, thinking back at Tesla and the pigeon, are odd romantic obsessions kind of an intriguing subject to you as a filmmaker?

I might be revealing more about myself than I should but yes it’s true – the pigeon, of course, is an animated object (laughs), it’s a creature, and a shoe is an inanimate object…so there’s a progress there, of some sort? Maybe in the wrong direction, I’m not sure!

The Tesla World Light screens as part of TIFF‘s Short Cuts Programme 06 from Sunday September 10th and OIAF‘s Short Film Competition 1 from Wednesday September 20th

Find Matthew Rankin online at rankino.com and for more on the work of the National Film Board of Canada visit nfb.ca