Interview with Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre, director of “Jutra” & “McLaren’s Negatives”

Marie-Josée Saint-Pierre, a Concordia University graduate, founded MJSTP Films in 2004 and has since built up an impressive, award-winning filmography including Passages, The Sapporo Project and McLaren’s Negatives which picked up over twenty awards and took festivals by storm. Her recent film Jutra is an animated documentary exploring the life and work of Mon Oncle Antoine director and A Chairy Tale co-director (with Norman McLaren) Claude Jutra, executed through the painstaking assemblage of animation and archival footage of the filmmaker himself. Having been selected as part of the Cannes Directors’ Fortnight last year, amongst its recent achievements is a Canadian Screen Awards nomination (UPDATE: Win) for Best Short Documentary next to Luc Chamberland’s NFB doc Seth’s Dominion. The film has also been nominated (UPDATE: Another Win!) for, fittingly, a Jutra Award for Animated Short alongside fellow NFB productions SOIF/Thirst (Michèle Cournoyer) and Nul poisson où aller/No Fish Where To Go (Nicola Lemay/Janice Nadeau). In the wake of last year’s McLaren’s Centenary Celebrations we take a look at how his and Jutra’s legacy has helped shape the artistic path of today’s animation filmmakers such as Marie-Josée.

Marie-Josée at Directors’ Fortnight in Cannes

How did you get started in the world of animated documentaries?

I live in Montreal, so in Quebec after High School you go to College before University, so I decided to study advertising. In the last year of my studies I could choose either PR or creation. I chose creation and, at the time, did a small 10-second animation with Softimage – so it was all programming, computer stuff but I really liked making the film and afterwards I decided I wanted to do film animation. So I moved to the big city and I went to university to do a BA in animation and a Master’s in film production. My MA film was a documentary called Post Partum. I guess I decided to mix the genre of documentary and animation together because of doing those two degrees together.

Has this pairing of animation and documentaries always appealed to you?

It actually wasn’t a choice – the first time I did one when I got out of school was because I wanted to make a portrait of Norman McLaren. I really like his work and I wanted to make something to pay homage to him. After I finished the film people called it an animated documentary, which I didn’t think about when I was making it, I just wanted to make something about him. So, as I said, it’s less a deliberate choice to make animated documentaries as I just find that people and archives and photographs really inspire me, so that’s why I make films about them.

You have several projects that deal with the world of Norman McLaren, notably the Jutra Award-winning McLaren’s Negatives. How did your enthusiasm for his work begin?

When you study animation, you realise how hard it is to make animated films. You spend weeks and weeks drawing and working and you end up with five or ten seconds! When I was a student, honestly, I wanted to drop out of school because I thought animation took just too long to make. Then I discovered McLaren’s work. I think he was the reason why I didn’t drop out of animation school, because I saw his work was so amazing. I think he’s my favourite animator/artist of all time, I was really inspired by what he was doing and also the fact he was always choosing different techniques, that in every film he did he tried to reinvent himself. I think it’s really important to do that.

Structurally these documentaries use quite a lot of existing footage weaved in such a way to tell its own story, how do you go about the planning of that kind of narrative?

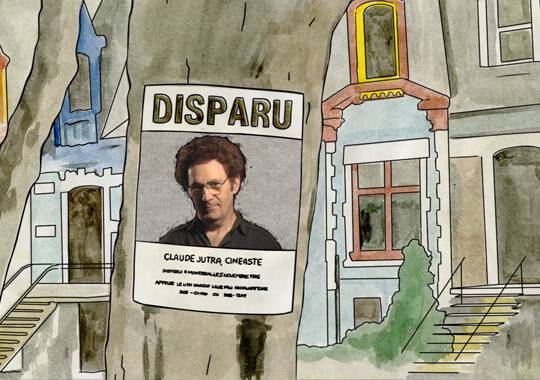

That’s a good question, because people don’t realise how hard it is to take live-action footage and intertwine it with animation. I mean, there’s always a lot of research needed for these images to gel well together. In Jutra it’s live action characters cut out and set against watercolour backgrounds, but when we did the cutting out of the character initially it wasn’t working because the edges were not very nice. So then we decided to add the scratches and everything, so there was always a lot of research to have the live action and animation go well together. It can easily be very ugly if you don’t do aesthetic research on what you’re doing and how you’re mixing it together.

Do you generally use digital process/softwares or are there any analogue processes?

All the films I’ve done are 2D animation. We use an early version of ToonBoom for animation by hand and to cut out all the shapes, then all the compositing is done in After Effects.

For those who may not be familiar with him, can you tell us a bit about who Claude Jutra was and the nature of his association with McLaren?

Claude Jutra was a Quebec filmmaker who is quite important in Canadian film history. He met McLaren when he was a very young artist starting his career and they did the film A Chairy Tale, which I guess most people know. I think McLaren helped Jutra start his filmmaking career, because then he went to France and he met Jean Rouch and Truffaut. The film I wanted to make was a portrait of Claude Jutra but what I was really interested in was finding out why – at 56 years old when he was at the top of his filmmaking game – he decided to commit suicide by jumping off a bridge. What I found when I was doing research was that he had found out that he had Alzheimer’s disease, so I think he knew what was coming up for him. Also there was the fact that it started to be really hard for him to make films, I think all those things together pushed him to it.

A Chairy Tale by Claude Jutra & Norman McLaren, National Film Board of Canada

The way Jutra’s put together, how he’s having conversations with his younger self, is very expertly done. What went into that as far as planning it out, sourcing the footage etc?

The thing is that, the way that I work, I’ve never made a storyboard in my life; I don’t storyboard because I believe that filmmaking is a very organic process, a film itself is alive and the shape changes and evolves when you’re working on it and editing it. The way I work is I always know how my film will finish, then I go back and start making it, so in Jutra the first scene I made was for the bridge sequence at the end of the film.

Claude Jutra is very documented – he gave interviews, he made interviews, he was a comedian in films – so this film could only have been made this way with him as its focus because there’s so much material. I didn’t plan to have him asking questions to himself at all but when I was working in the editing room at one point I thought What if I cut the image in half and I put one Claude Jutra on one side and one Claude Jutra on the other side? I tried to move them and they looked they were talking together, so then I knew I had something. Really it happened in the editing room, working with the film, which is why I don’t limit myself to storyboards or scripts because then I can go further with my filmmaking.

Do you have a basic structural idea of how it’s going to come together or is it completely on the fly?

Honestly, when I write a project and try to get some money for it, I’m going to go more for a documentarian style of writing. If you saw the images I made for my financing compared to the final film there’s no correlation, they’re very different.

Also released last year was Flocons (Snowflakes), which was particularly fascinating in the sense that it makes use of previously unseen McLaren footage. How did you come to discover and put together what is in some respects a ‘lost film’?

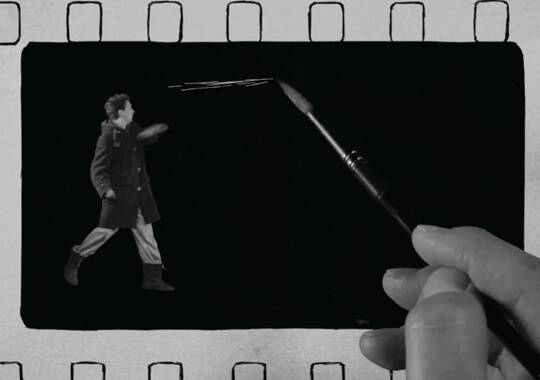

That’s kind of a crazy story. I think it’s like a karmic kind of thing, having made films both about Claude Jutra and Norman McLaren. When I was working on Jutra we found that Claude had given lots of his personal artifacts to the Cinémathèque québécoise. Amongst them were negatives, but nobody knew what was on them, so my co-producer at the NFB gave me permission to transfer them at the Film Board. I think there were two or three hours of material that wasn’t that great, but then there was this two and a half minute shoot that looked exactly like it was shot at the same time as A Chairy Tale, because it was the same performer, the same framing and everything. So then I was trying to make a film out of it, but who am I to finish McLaren’s and Jutra’s film, right? So it had to be contemporary, I tried to use compositing in a way to make it interesting. At the beginning of the sequence, for about 10-15 seconds McLaren had scratched snowflakes directly on the film. I found that making a two minute film of just Claude Jutra playing with snowflakes would be pretty boring, plus I wanted McLaren to be in the film because I knew he was behind the camera, so that’s why I added the sound and music and composited McLaren playing with Jutra in the film.

Shortly after Jutra was made it was selected for Directors’ Fortnight in Cannes, was this important early on in getting visibility for it?

The selection at Directors’ Fortnights was really great for the film because it really put a spotlight on it, we got a lot of screening requests since. It’s great but I don’t know, some filmmakers finish a film and they’re really attached to it; When I finish a film and I’m just happy I’m finally done with it! I release it to the universe and I’m glad if people watch it. It’s strange, sometimes you can make films really quickly, sometimes it takes forever if a film doesn’t want to be made. Then sometimes you make a film you think will have a good reception but you don’t, really. With Jutra I was kind of worried it wouldn’t resonate with people internationally, because they don’t know Claude Jutra, but actually the opposite has happened – I feel like it resonates more internationally and less in Quebec. I don’t know why that is.

Is it possibly because, to an international audience, it’s more a case about learning about his work for the first time, in an interesting way?

I’m glad there are people I’ve been interviewed by who didn’t know Jutra but they like his persona in the film. I think Claude Jutra should be more known, part of the point of making the film was wanting people to go see his films. It’s the same thing with McLaren, I was always surprised when some people – even in animation sometimes – don’t know Norman McLaren! I mean this doesn’t seem possible! I mean, kids don’t seem to know their history and they really should be more interested. That’s why I make these films, so people might find them and become interested in great filmmakers.

You’ve made several other films in between, when it comes to these films what tends to determine the subject – are you approached by other parties/clients or are they generally personal films?

I have two tangents in my work, I do portraits of famous artists and I also do more personal films about women’s issues. So right now I’m doing one on Oscar Peterson, and I chose him because I love his music and I think he’s very inspiring. I find when you make portraits of people like that, who are famous, it takes so long to do that you really have to be in love with them, otherwise you don’t finish the film. For my other work I project myself a lot in my films, so it’s always stuff that relates to me.

For more information on Marie-Josée’s work be sure to visit MJSTP Films