Magic Wilderness: The Adventures of Prince Achmed

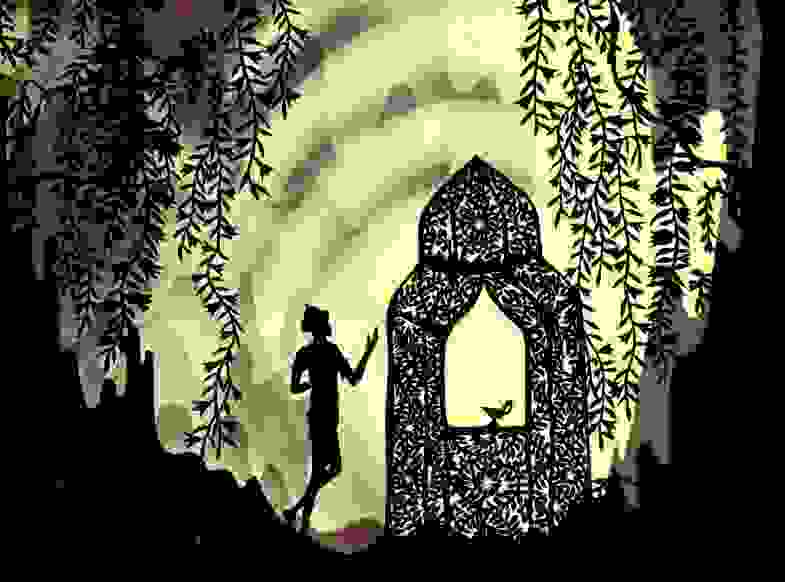

Having grown up in the 1970s, when most silent classics seemed either to be irretrievably lost or seen only occasionally and in faded, scratchy prints, I love living in a time when early masterpieces are regularly rescued and restored to glowing perfection, then offered to me to buy for the price of an indifferent pizza. 1927’s The Adventures of Prince Achmed, the earliest surviving animated feature, is a prime example. Its creator, Lotte Reiniger, was born in Berlin in 1899, and grew up with an obsessive love of cut-out silhouettes. In 1921 she began to apply her paper-cutting skills to animation and never looked back, creating dozens of short films over the next sixty years. In a few short years she was closely enough allied with Berlin’s film-making elite that she was able to find sponsorship for a feature film.

The story of Prince Achmed is woven from elements in various tales from The 1001 Nights of Scheherazade, and the result is pacy, enchanting flying-carpet of a narrative:

“Great was the power of the African sorcerer”, we’re told, as a slender and sinister figure conjures up magical animals from swirling patterns in the air. He creates a mechanical horse, which he offers to the Caliph of Baghdad in exchange for any of his treasures. Naturally he chooses the Caliph’s beautiful daughter, Princess Dinarzide, but her brother, Prince Achmed, steps in to fend him off. The sorcerer disposes of Achmed by tricking him into having a go on the horse without first explaining the controls, for which the Caliph has the Sorcerer thrown into prison. Achmed lands on the magical island of Wak-Wak, where he falls for another beautiful princess, Peri Banu, who is being held captive there by the island’s magical demons. He abducts her and whisks her off to China, where she is in turn abducted by the Sorcerer (by disguising himself as a kangaroo, oddly), who sells her to the Caliph. He then abducts Achmed – lots of abductions in this film – and traps him in a volcano, where he meets the Fire Mountain Witch, the Sorcerer’s arch-enemy. Meanwhile the demons of Wak-Wak, have found her again and, yes, abducted her back to their island. Achmed follows but is stopped at the gates, which can only be opened by the magic lamp of Aladdin.

Providentially, Achmed encounters Aladdin just as he’s being attacked by a mammoth-like creature, and rescues him. But where’s the lamp? Aladdin explains that he had it for a while and used it to build a magic palace to charm Princess Dinarzide. Unfortunately the Sorcerer turned up and stole the palace, the lamp, and of course the princess..

The Witch agrees to fight the Sorcerer to get the lamp back, leading to a dynamic, epic battle between the two, reminiscent of the Merlin / Madame Mim confrontation in Disney’s The Sword in the Stone. Naturally she wins, Achmed rescues Peri Banu, Aladdin gets back both the lamp and the palace, thus winning over the easily-impressed Dinarzide, and we get two happy-couple endings for the price of one.

From a modern perspective, it’s interesting to note how what passes for acceptable behavior for heroes has changed over time. Although the villain is clearly a villain, the actions of the heroes are not always beyond reproach. Though I suspect this is more due to the writer just following her muse than to any conscious or systematic attempt to provide a fairy tale with layers of moral texture, it does make the film a richer, less predictable watch than a micromanaged Disney offering in which any dubious behaviour by the protagonist would either be snuffed out at the story stage or would only be there for the hero to learn from his mistakes. One can imagine the notes that would come back from head office if this film were in development at a major studio: Why is it bad for the villain to abduct the princess, but acceptable for the hero to do so? Should Aladdin not show more nobility to win the princess than offering a magic palace conjured up by a genie?

On the other hand, Lotte Reiniger’s impish sense of humour is evident elsewhere in the film – for instance when Achmed narrowly escapes the clutches of Peri-Banu’s houseful of sex-starved ladies-in-waiting – so perhaps she enjoyed the idea of having her charming heroes get away with stuff that lesser beings wouldn’t.

On the other hand, Lotte Reiniger’s impish sense of humour is evident elsewhere in the film – for instance when Achmed narrowly escapes the clutches of Peri-Banu’s houseful of sex-starved ladies-in-waiting – so perhaps she enjoyed the idea of having her charming heroes get away with stuff that lesser beings wouldn’t.

The cut-out animation technique is fascinating to watch, as it’s the direct ancestor of many productions made for television today. As a pioneer of the technique – especially in the field of fairy tales – it’s likely that she was a direct influence on the animators of British TV’s Golden Age, such as John Ryan and Oliver Postgate – especially as many of her films were shown on the BBC in the 1950s and early 60s. Noggin the Nog and his contemporaries are, in turn, the ancestors of today’s CelAction productions. So as a CelAction animator myself, I owe Lotte Reiniger a debt of gratitude.

Then as now the cut-out approach allows a single animator to produce far more work in the same time than would be possible for all but the simplest drawn animation, though even today few have followed her lead in animating a feature film almost singlehandedly. The problem isn’t just technical – one of many reasons Disney was so successful is that their films are so rich in character, colour and detail. The eye does not tire of them too quickly. It takes resources to achieve this. The simpler the imagery – the further removed from reality – the harder it is to sustain the audience’s attention; to suspend their disbelief in the world they’re looking at. Creating an entire animated feature with such economy of style and technique that a single artist can do the bulk of the work, and still have an end result sufficiently rich in story, character and design that it can hold the attention for the length of the film, is probably the hardest trick in animation to pull off. Curious that the earliest surviving film to do so is also the earliest surviving animated feature.

Items mentioned in this article:

![The Adventures Of Prince Achmed [DVD]](https://www.skwigly.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/The-Adventures-Of-Prince-Achmed-1926-DVD.jpg)