Magic Wilderness: El Apóstol & Peludópolis

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the release of the world’s first animated feature film, so I thought it would be appropriate to celebrate this with a series of articles on selected films. As we all know, Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is usually cited as the first animated feature, but as most of us who read this site are no doubt aware, it wasn’t. It was preceded by Lotte Reiniger’s The Adventures of Prince Achmed, Ladislas Starevitch’s The Tale of the Fox, and two features by the Argentinian animator Quirino Cristiani – all films which could scracely be more different from the Disney model. Their creators were pioneers in the medium every bit as much as Disney and his team were, but achieved strikingly different results. So sucessful were Snow White and the subsequent Disney features that all other approaches to the medium have largely been eclipsed by it – or consigned to the wilderness. A magic wilderness, if you like, beyond the borders of the Magic Kingdom – hence the name of this column; a tribute to those films which have dared to explore routes beyone Disney’s safe and well-trodden paths. (Skwigly’s editor Steve suggested other names but I dismissed them as being inadequately pretentious).

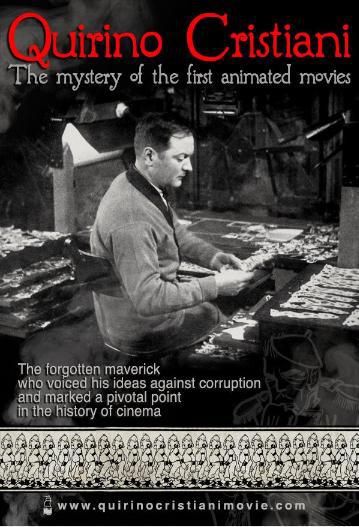

The first animated feature was El Apóstol, created by Quirino Cristiani in Argentina and released in Buenos Aires in November 1917. Sadly neither this film nor any other of Cristiani’s works (with one or two short, tantalising execptions) have survived, but their history and his has been painstakingly traced and recorded by Gabriele Zucchelli in an excellent 2010 documentary, Quirino Cristiani: The Mystery of the First Animated Movies.

Cristiani was born in Italy in 1896 but he and his family emigrated to Argentina in 1900. In a familiar story, his parents hoped he would be a doctor but he disappinted them by becoming an artist instead, then again by dropping out of art school to be a mere cartoonist. However he excelled at this, especially in the art of political and satirical cartoons which were popular in Argentina in those turbulent times. His work attracted the attention of Federico Valle, a pioneering newsreel producer, and Critiani was hired to create static cartoon images to add to those newsreels. Valle asked if it was possible to make them move, but Cristiani had no idea how to do this and had to devise a technique for himself. He studied the work of Emile Cohl – most likely his cut-out series The Newlyweds rather than the earlier, drawn Fantoche cartoons for which he is best remembered today – deduced how they worked, and developed his own system of cut-out animation using hinged figures.

Impressed with his results, Valle hired the most high-profile designers and writers and bankrolled El Apóstol, a feature-length political satire animated entirely by Cristiani. The film poked fun at the then president, Hipolito Yrigoyen, who had recently come to power on a wave of popular support and with the aim of clamping down on corruption. In the film, Yrigoyen dreams of achieving this with thunderbolts borrowed from the god Jupiter, then awakes and realises that the solution is not so simple.

The film played exclusively in one cinema in Buenos Aires, but was hugely sucessful with both critics and audiences, running for six months with seven screenings a day.

This should have been the start of a stellar career for Cristiani, but sadly it proved to be the peak of his success. He tried to follow it up with a second feature called Without a Trace, which focused on a devious attempt by the German ambassador to bring Argentina into the war by attacking her ships and blaming it on the Allies. However the city governor confiscated the film after its first screening, deeming it too politically sensitive, and it was never seen again.

As the 1920s took hold, cinema was becoming more a vehicle for fantasy and escapism than for satire. Cristiani made a few animated commercials but found he was being undercut by live-action. He spent most of the decade making Spanish intertitles for imported American films – hardly a satisfying vocaction for such a gifted artist – and in 1928 Valle’s studio caught fire, destroying all of Cristiani’s work to date.

In 1931 he made another feature, Peludópolis, again a political satire backed by Valle and focusing on President Yrigoyen. However it had to be reworked at the last moment to placate the new president, General Uruburu, who had taken over in a military coup. The final film was probably softer on the the new dicator and harder on the Irigoyen than Cristiani would have liked. Yrigoyen died soon afterwards, and Cristiani expressed regret in later life at having directed his satire at such a well-intentioned politician.

Cristiani returned to his bread-and-butter work of retitling imported films before settling down to a peaceful retirement. Peludópolis and all but one of his other films were destroyed in further fires in 1958 and 61, so now almost nothing of his work survives except a tantalising reel about the making of Peludópolis, rediscovered by Zucchelli while he was researching this documentary, and some video of him as an old man in 1981, demonstrating his animation technique during an invited visit to his native Italy by animation historian Giannalberto Bendazzi, without whose efforts Crisitani might have been forgotten altogether. The grace and sensitivity with which Cristiani executes a short fragment of film makes the loss of his life’s work all the more poignant.

Quirino Cristiani: The Mystery of the First Animated Movies is a fascinating and humbling documentary, but my personal favourite part of the DVD is on the extras – an interview with veteran London animator and expat Argentinian, Oscar Grillo, in which he expresses his frustration that modern-day animation is so much less adventurous and daring than Cristiani was. “We live in terrible times. Our big governments are attacking countries like Iraq, but I don’t see a single animation done in the USA, the UK, nor France, Italy nor Argentina against the injustice, or even to justify it for those who agree… we live in a dangerous, complicated and difficult world, yet nobody has the balls to use [animation] to explain what is going on.”

Seven or eight years after Oscar Grillo recorded that interview, Cristiani’s example is more relevant than ever.

Quirino Cristiani: The Mystery of the First Animated Movies is available to purchase on DVD. Copies of the DVD can be purchased on the films companion website here.