Laloux & Topor’s Beautiful World: The 50th Anniversary of Fantastic Planet

Fantastic Planet

© Les Films Armorial, Ceskoslovenský Filmexport

Arguably one of the biggest cinematic events in the world, the Cannes Film Festival celebrates its 76th birthday this year and even with a plethora of anticipated premiers of major blockbusters and independent films to discover, animation enthusiasts attending will be treated to Pixar’s Elemental and the latest adaptation of the popular French children’s book Little Nicholas.

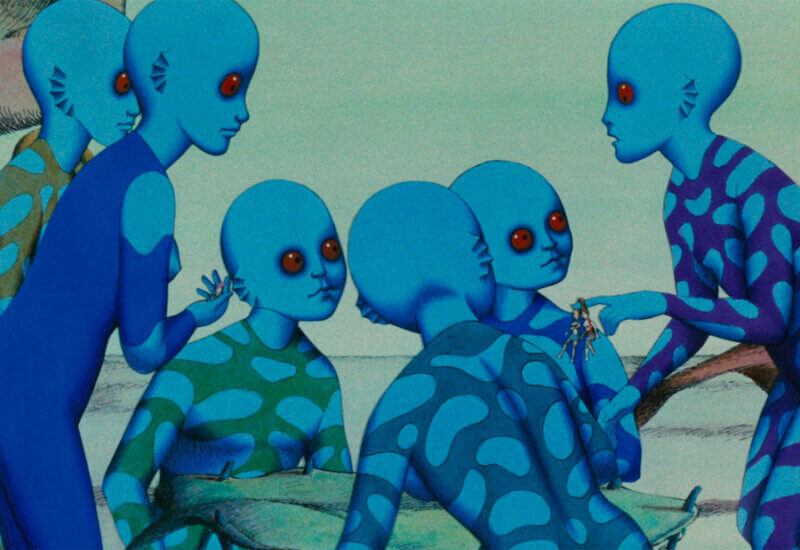

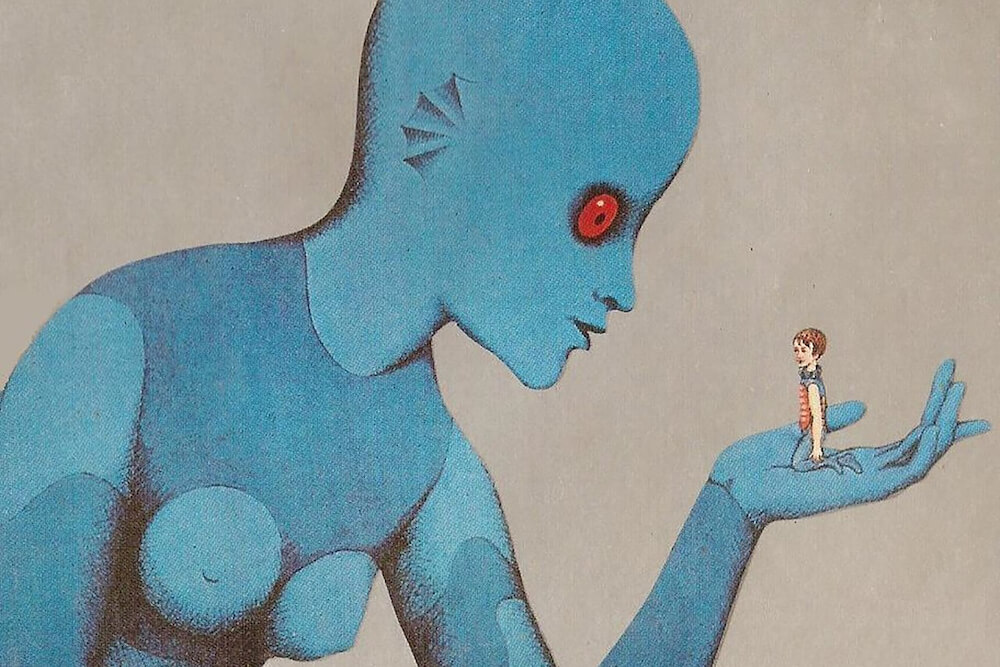

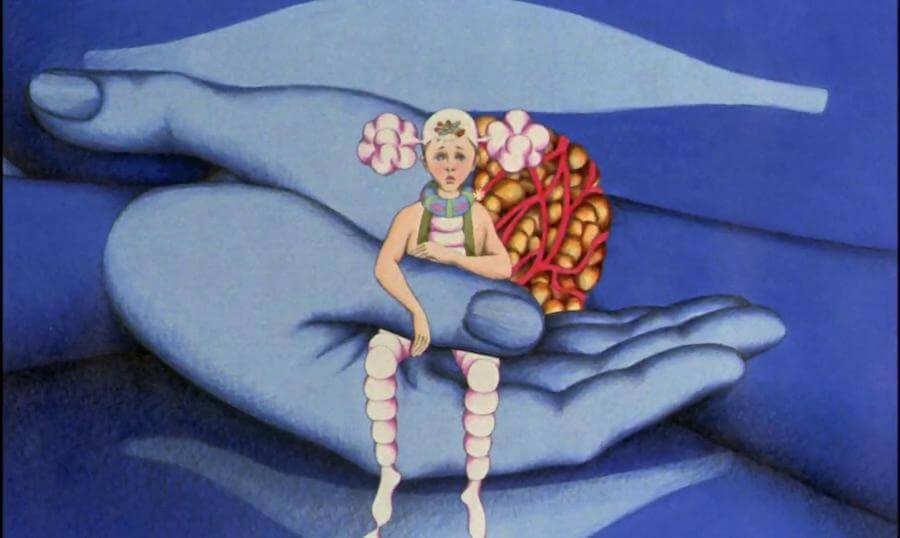

Arguably one of the most bizarre, yet celebrated, animated films to ever premiere at the iconic French film festival is Fantastic Planet. Set on a distant planet within deep space, it tells the story of two alien races, the gigantic and powerful Traags and the petite and puny Oms, as they come into conflict after the latter are all tired of hiding and being hunted by their superior rulers. Standing out from the crowd when it premiered in 1973, its surreal designs, experimental use of cutout animation, and a more mature story compared to other animated releases that year, it was awarded the Grand Prix special jury prize.

While today the film is regarded as one of the best-animated sci-fi tales for adults and will celebrate its 50th anniversary this year by fans since its first screening, it certainly had many obstacles to overcome and found its way miraculously all over the world. With a more family-friendly market to compete in and challenges with a changing political landscape, this film could have become an incomplete and unheard-of project. Among the talented animators, supportive production companies, and crew members, two particular people were recognized in the history of the film’s development and guided it through its hurdles in order to get it made with their ambitious vision intact.

Working as an art therapist at the Cour-Cherverny Psychiatric Clinic in Orléans in Northern France, René Laloux (1929 to 2004) may have had a different direction in his early career as an artist, but his work with the patients and other staff members within the institute would see him find a passion for filmmaking and, eventually, become a recognized director. He performed puppet shows for his patients and supported them through creative and artistic outlets while working there in the 1950s. He learnt to tell stories and help bring people’s visions to life which saw him move onto an ambitious, yet exciting, project.

He decided to create a short animated film, in which the patients would write the story and provide the artwork for Laloux to direct and animate. Working alongside the patients as well as some of the eager interns who wanted to help them, he eventually completed The Monkey’s Teeth in 1960. Telling the story of a dentist who steals teeth from the poor and gives them to the rich, he was able to use cut-out animation to bring all the characters that the patients created to life. This peculiar experiment may have been an ambitious attempt to help those he taught during his time at the institute, however, it would also be the spark that would see Laloux go down a path as a director.

Winning the Emile-Cohl Prize for the best-animated film for the year of its release four years later in 1964, Laloux met an ambitious artist and writer at the award ceremony named Roland Topor (1938 to 1997,) who would become a key figure for both of their future film careers and was later seen as one of France’s most extraordinary creative figures in the 20th century.

After the Second World War, Topor attended the Ecole National Supérieure des Beaux in Paris as a student and during his time spent in the classroom, he discovered surrealism as well as comedic films created by The Marx Brothers and the Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch (1450 to 1516.) Influenced by so many talented people creating films and inspiring artwork both new and old, Topor would explore many outlets to express his creativity. He joined a group of artists in 1960 who would be responsible for the creation of the infamous and controversial Charlie Hebdo publication. His artwork even stood out compared to the other artists that made the magazine, drawing one page-filling panel rather than a bunch of smaller pictures and comics together to demonstrate his often surreal art with hauntingly striking figures taking centre stage.

After their initial meeting at the award ceremony, the two hit it off and collaborated on two short films named Dead Times and The Snails. Released in 1964 and 1965, these two short films demonstrated how brilliantly both of the artists’ talents blended to create some visually striking pieces of animation, with Laloux continuing at that time to use and build upon his skill of cut-out animation and bringing Topor’s detailed and exaggerated characters to life in his equally unique and versatile landscapes and backgrounds. With the release of these films as well as Topor’s eagerness for exploring new avenues, he eyed up French author Stefan Wul’s sci-fi novel, Oms en série, as their next animated production. But rather than turning it into a short film, the two wanted to adapt it as their first feature-length project.

Once the two penned the script for their sci-fi tale of inequality and savageness, they were able to find several production companies across France and the Czech Republic to help finance the project and started animating in Prague in 1968. However, just as the film’s production was underway, the country was invaded by the Soviet Union, which ultimately interrupted the film’s progress for a whole year. After gaining some additional financing to continue their production, Laloux and Topor were able to resume in Paris. Making a short film with cutout animation would have certainly taken some time, but using the many exaggerated aliens and locations scattered across Topor’s fantastically designed planet with a feature-length running time saw it take nearly five long years to be completed. After the team of animators’ commitment and being able to relocate during a changing political landscape, the film was finally completed and premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 1973.

At this point in time, cutout animation was used for popular films and television shows that many were familiar with, including Yellow Submarine, Monty Python’s Flying Circus, and Captain Pugwash. But while these properties took audiences on fantastical adventures across the world, they were not able to teleport them to other planets and witnessing intimidating aliens years before the popular rise of sci-fi films in the 1970s like Star Wars, Alien, and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, making it stand out even further from the crowd at Cannes. So how and why did it become a cult film after all of these years rather than being as fondly remembered as any other ground-breaking piece of science fiction? And despite its hurdles to be seen outside of the festival, how did it influence the animation industry years after its premiere?

Despite its striking imagery and designs, the film was competing with Disney’s more family-friendly stories and expressive hand-drawn animated characters with Robin Hood pleasing children as much as adults when they went to the cinemas in that same year. And with little competition at the time, Disney dominated the market when it came to animation. Fantastic Planet would eventually find its cult status on the home market after the release of the VHS tape in 1976 among others who also couldn’t quite find their way to audiences at the cinemas. It had several re-releases since then with the introduction of DVDs and Blu-rays that gave the film more opportunities to be discovered and made itself recognised by more people.

It may not have been the only piece of cutout animation in the 1970s, but it and these other unique productions did make an impact on the industry between the 1980s to the 2000s due to their artistic and experimental approach to the aesthetic that no other forms of animation could quite accomplish. The bands Talking Heads’ And She Was and Tears for Fears’ Sowing the Seeds of Love incorporated this form of animation into their music videos for these singles and gave them a unique flavour with the rise of MTV in the 1980s. And while cutout animation may not be used as much as it was fifty years ago, filmmakers and producers did continue to use this format to create some truly interesting projects. George Lucas would go on to produce his first animated film with this approach in 1983’s Twice Upon A Time while early episodes of hit television shows like Blues’ Clues and South Park used it before they switched to computer animation in the 1990s.

Fantastic Planet

© Les Films Armorial, Ceskoslovenský Filmexport

Roland Topor may not have worked again on an animated feature, but René Laloux on the other hand would make two follow-up films, Time Masters (1982) and Gandahar (1987) that would also receive cult statuses from fans of his work. But what made Fantastic Planet stand out from Laloux’s trilogy was Topor’s brilliant and beautiful designs, making a sci-fi title that is as fresh and unique with today’s large collection of films and shows in the genre as it was back in 1973.

Currently available on the BFI Player, this 50-year-old animated classic shouldn’t be missed for its warped and psychedelic alien world and an extraterrestrial tale of inequality and freedom that resonates as much today as it did upon its release. Those who enjoy this unique and creative form of animation and thought-provoking science fiction should not miss the opportunity to celebrate this film for its remarkable achievements and accomplishments by these two talented French artists.