Interview with Justine Vuylsteker (‘Embraced’)

French filmmaker Justine Vuylsteker‘s first professional auteur short film Étreintes (Embraced), screening this week in competition at the Annecy International Animated Film Festival and Anima Mundi next month, is “a bittersweet visual poem” that, through a variety of sensual and intimate visual sequences, tackles the struggles and yearnings of a woman whose past and current relationships are at odds with one another.

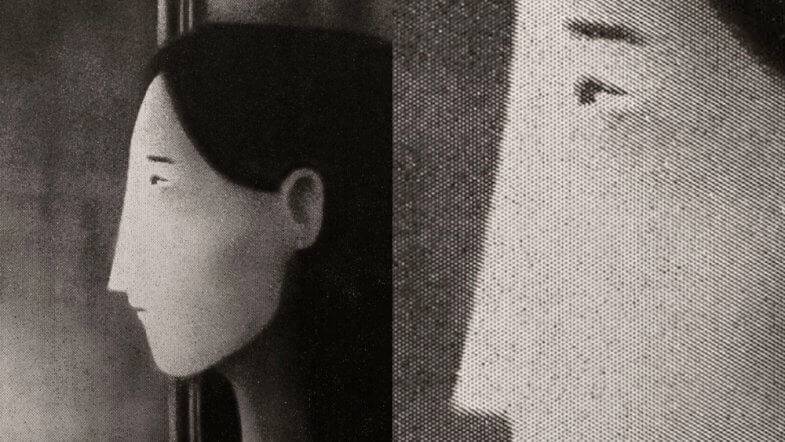

Co-produced by Julie Roy of the National Film Board of Canada and Rafael Andrea Soatto of Offshore, what makes Embraced markedly unique among the Annecy selection is the rarity of its animation method. To create the intimately-detailed visual scenarios the film depicts Justine was able to make use of one of the few remaining pinscreens still in use, Alexandre Alexeieff and Claire Parker’s “Épinette”. Mastery of the pinscreen animation technique – whose origins lie in the French first avant-garde and in which a large-scale pinscreen in painstakingly manipulated to create images from the light and shadows cast by the innumerable pins encased in it – has been achieved by few, although among its number are the likes of Norman McLaren, Jacques Drouin and Michèle Lemieux.

Skwigly spoke with Justine Vuylsteker to learn more about the challenges and advantages of a film with such unique production circumstances, whose end result is nothing short of visually breathtaking.

Can you tell our readers a bit about yourself and what led you to filmmaking?

I would say that the source of this desire to make films was an eagerness to share sensations. The hope that someone else might be able to experience a sensation that enthralled me and that I can’t convey in words or speech. So, a kind of frustration with language, which led me to a mode of expression where textures, light, time and silence address our senses directly. Hence the choice of animation, which spurred my interest in the languages of materials: an exploration that I began with paper for my final-year student film Fish Don’t Need Sex, then bringing sand into the mix for the commissioned film Paris, and most recently continued with the pinscreen for my first professional auteur film, Embraced.

There are very few artists these days who still make effective use of a pinscreen for animation, what drew you to it (and, given how rare they are, how did you manage to get started)?

My journey to the pinscreen was a series of coincidences and synchronicities that still amazes me whenever I’m asked to talk about it. It started in 2012. I was almost 18, and I was looking to impress the admissions jury for the animation program I wanted to enroll in. So I went to see an exhibit to soak up a few references… and there I experienced an aesthetic awakening: Night on Bald Mountain, by Alexandre Alexeïeff and Claire Parker. That film blew me away. At the same time—but unbeknownst to me—the CNC had been working for some years to acquire and restore the last pinscreen that Alexeïeff and Parker had built, called the Épinette. Despite the impact that seeing Night on Bald Mountain had on me, the idea of working on a pinscreen never crossed my mind; it was way too far out of reach. But I was fascinated by the technique, and throughout my studies I took every opportunity that I could to learn more about the pinscreen. Flash forward to 2015: the restoration of the Épinette was completed, and a call for candidates was issued in France to form a group of eight filmmakers to be introduced to the instrument. I had just finished Paris, so I put an application together right away! I was lucky enough to be selected, and just before the 2015 Annecy Festival, the internship began, under the attentive supervision of Michèle Lemieux. As for the rest of the story, well, it’s the story of creating, and making Embraced!

Justine Vuylsteker (Photo: Stéphan Ballard)

For those reading that have never seen or used one, can you describe what precisely a pinscreen is and how images are created with it?

A pinscreen is a rectangular panel, about 5 cm thick, mounted vertically. The entire surface is pierced by tubes, in which pins are set. The pins extend beyond the surface, so you can vary the relief that they create at the surface of the screen. But the key thing to remember is that the source of the image, what the camera is going to record, isn’t the pins: it’s the shadows projected by the pins. The light source is fundamental: without light there is no shadow. And it’s the shadows that create these infinite shades of grey. To explain it precisely: the farther a pin extends from the surface, the longer the shadow it projects, and the deeper the black that our eye perceives. Conversely, the farther you push the pin in toward the screen, the less light it catches, and you get lighter greys, all the way to white if the pin is fully depressed. And obviously you don’t work with one pin at a time! You sculpt pins in masses, in groups, to the degree of grey that you want.

Can you tell us a bit about the history/significance of The Épinette and the circumstances that allowed you to use it for this film?

The Épinette is the last pinscreen that Alexeïeff and Parker built, in 1977. It’s often said that the Épinette is the twin of the NFB’s screen, the NEC. But there are a few differences: they’re not exactly the same format, and one was mounted horizontally while the other was mounted vertically, which leads to a slight difference in the graininess of the images obtained.

There’s also the fact that the Épinette is somewhat more weathered than the NEC, which has been in use since it was built and has therefore been properly maintained. And in spite of the fantastic restoration job by Jacques Drouin and Michèle Lemieux, jointly with the team at the CNC led by Jean-Baptiste Garnero and Sophie Le Tetour, the Épinette still has some scars on its surface, some irregularities, and the white of its surface is creamier than that of the NEC, which is immaculate. But to be honest, I find all those imperfections deeply moving. I think it’s those slight defects that make images created on the Épinette especially sensual and arousing.

How did you get involved with the NFB and Offshore, and what areas of the film did they contribute to most during production?

The first to get involved was Rafael Andrea Soatto of Offshore. We met at the end of 2015, just as I had finished one month working on the Épinette (each of the eight filmmakers got four weeks with the screen to become familiar with it and hopefully spark a film project). He had liked my film Paris, and when he heard me talking about the pinscreen, he wanted to learn more. We clicked right away, and he was on board with the project right from the writing stage. Julie Roy at the NFB also helped birth this project, initially at a distance and then in an official capacity, just before shooting began. Whereas with Rafael we worked on the intentions—on defining the essence of the project so that I wouldn’t lose my bearings during shooting—Julie’s role was to make sure I successfully conveyed those intentions to the viewer, so that the poetry of the film would really speak to the people watching. Another wonderful consequence of the NFB’s involvement was the opportunity to work with the technical crew who, having worked with Jacques Drouin and Michèle Lemieux, have expertise with the specifics of images produced with the pinscreen. Their input was invaluable to the final look of the film.

What inspired the story of Embraced?

Being face to face with the Alexeïeff-Parker pinscreen. The love story came naturally from that encounter. I can’t look at the Épinette without seeing, in the shadows, how it is the fruit of, and a testimonial to, the love between this couple. I can’t help picturing how they worked, each on one side: this silent dialogue they had across that screen, that interface, between them… This image of them working was one that dominated all others, and it was with me permanently while I worked on the Épinette. It was the seed of Embraced. And mixed in with all that was the sheer sensuality that the instrument gives off, and the intimacy of manipulating it. And melancholy: this gaze back at the past; surely the result of working with this tool out of another time, that makes you forget what day, what year and what century you’re living in when you work on it. Suspended time—a sort of nowhere. And a lot of poetry, Pushkin and T.S Eliot in particular… Somewhere in the midst of all that, the story of Embraced emerged.

Embraced (Dir. Justine Vuylsteker)

Given that a pinscreen’s functionality necessitates a lot of straight-ahead animation was there much by way of pre-visualisation you worked on for the film (storyboards, tests etc) or was it more of a stream-of-consciousness/improvisation?

The whole question of preparation was a huge concern for me while writing the film. How do I exploit this potential for improvisation, but at the risk of getting completely lost? I had six months of shooting time, and at the end of those six months all the material needed to make the film had to be shot. So there was this absolute need to produce usable material, and constantly. But I was dead set against channelling the film into a set structure, with a storyboard or an animatic, when the dialogue with the pinscreen hadn’t yet begun. So how would I build a frame that was both solid and flexible, as a guide to shooting? That questioning led me to make a very long, uninterrupted drawing (14 cm x 200 cm), containing the substance of all the motifs, gestures and settings of the film, but without any shooting script, movement or timing—those were decided during the time I spent shooting.

Did you use any compositing or animated layers to create the final visual (if so I’d be curious as to some of the practicalities of the process)?

Everything was shot in a single layer. What you see on the film screen is what was on the pinscreen—except for one shot, where you have a simultaneous shift, the image disappearing into black on the right, with white appearing on the left. I was at the end of shooting, really tired, and starting a shot over at that point was pretty much impossible. I didn’t want to risk not being able to synchronize the appearance and disappearance the way I wanted. So I shot it in two passes: the right, then the left. And the compositing to put the two together was pretty basic. But for the rest of the film, what you see is what was on the pinscreen.

At a certain point in the film (the close-up kiss) it even seems rotoscoped, is this the case and if so how was that achieved using the pinscreen?

You’re absolutely right, it’s rotoscoped. I used a feature of the DragonFrame software that allows you to superimpose a live camera view onto a layout (fixed or animated), and that served as my guide.

Embraced (Dir. Justine Vuylsteker)

How has working in this way affected your general artistic/storytelling process, if at all?

When we make animation, we stage bodies that aren’t made of flesh and bone. We film invented characters, illusions that no one will ever be able to touch. Bodies that are profoundly absent. Since Embraced deals precisely with absence, with memories that are practically hallucinated because they appear so tangible, I was interested in playing up that ambiguous presence-absence of the body, which animation naturally triggers. That’s why I used rotoscoping, which, it seems to me, heightens the arousal by evoking the memory of a “real” bodily presence behind the animated material.

Do you hope to use the pinscreen again for future work?

Absolutely! But not right away; for now, I very much want to go back to paper. Mostly because I need to take the time to properly digest the experience of having made Embraced, which was both incredible and taxing, and hopefully incite a new fruitful dialogue with the Épinette.

See Étreintes (Embraced) this week as part of Annecy’s Short Films in Competition 3.

To see more of Justine Vuylsteker’s work visit justinevuylsteker.com