Interview: Jonathan Hodgson on his latest film ‘Roughhouse’ – a raw portrayal of bullying

For someone who doesn’t consider himself a good animator, Jonathan Hodgson has made remarkably good as one. Raised in Birmingham, he began to show interest in the medium at the same time as Britain’s institutions did. He enrolled on fledgling animation courses at Liverpool Polytechnic and the Royal College of Art, developing a rugged caricatural style that married pin-sharp social observation with flights into abstraction.

The success of his student films in the early 1980s set Hodgson on a three-pronged career path. While continuing to work on personal projects like the Bafta-winning Bukowski adaptation The Man with the Beautiful Eyes (2000), he launched sidelines in high-profile commercials and commissioned films. Recent years have seen him produce a run of documentary shorts – mostly centering on human rights abuses – for the likes of Amnesty International and The Observer.

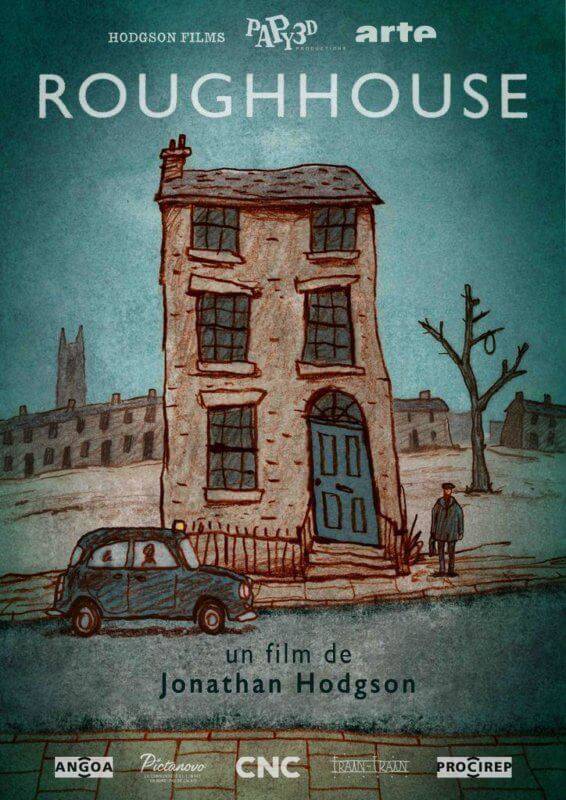

Roughhouse puts an end to that run. A narrative film about the social dynamics in a student house, it’s the rawest portrayal of bullying in animation since JJ Villard’s Son of Satan (2003), and Hodgson’s most intimate work in over a decade. After experimenting with mixed media in his commissioned films, Hodgson returns to the hand-drawn aesthetic that made his name; but that isn’t Roughhouse’s only familiar ingredient. For the setting is Liverpool Polytechnic in the 1980s, and the punky protagonists look not unlike Hodgson in photos from that era…

A few days before the film picked up a Bafta nomination, I met up with Hodgson for a pint and a chat.

On the face of it, Roughhouse is unlike your other work in that it’s a straightforward fictional narrative. But how fictional is it, really?

It’s something that happened. I changed some of the events, but I did live in a flat in Liverpool. We were three friends from Birmingham, and one of us got into a situation where he couldn’t pay the rent. Me and the other guys in the flat, some of whom were northerners, were pretty pissed off with him, because we were having to pay his share of the rent and he wasn’t doing anything in return. There was playful violence, but also psychological… when we became really unfriendly to him, that was the thing he found hardest to handle. The problem could have been sorted out in a more mature way.

Is he “Martin”, to whom the film is dedicated?

Yeah. I’m not really in touch with him. I don’t think he knows I’ve made the film. I do feel a bit awkward about that. I felt like I should have asked him, but if he’d said no, I wouldn’t have been able to make it.

You started developing the idea for Roughhouse around ten years ago. Why did the story come to you then?

We used to talk about how dreadful our lives were when we were students, how badly we behaved, and this story came up again and again. It would start out as a funny story, people would laugh, and then I’d start getting really emotional telling it. I felt really bad at the time. I think I’ve always carried around a certain amount of guilt about it. We thought we had reasonable justification to almost dehumanise Martin. That’s under the surface for a lot of people.

I’d made a couple of films… Feeling My Way is about what’s going on in your head as you’re walking to work, and Camouflage is about growing up with a schizophrenic parent, and how that affects you. So I was interested in using animation to convey psychological states, and have a kind of interface between an internal and an external narrative. It’s something that animation is very well suited to. Roughhouse started out as a documentary, but then I thought telling it like I was in a pub is a nice, honest way of doing it.

Robert Bradbrook and Yael Shavit are credited as script consultants. How did they get involved?

I know Robert well. He joined the team at Middlesex [University, where Hodgson leads the BA Animation course], and I saw how incredibly good he was at editing stories. He re-edited the film quite a bit. He’s helped me with a few films in the past. Yael is the partner of Steven Camden, who narrates Roughhouse. I knew that she was doing script reading for Film London – she’s a theatre director – so I just asked her if she’d look at my script. She was really helpful. Robert was about tightening things up, whereas her input was the emotional side of it. Where she helped a lot is in making it more my own story.

This is the first film you made in France.

I’d applied for funding from a few sources in the UK and wasn’t getting anything. And then I was on the jury at Animateka Festival in Ljubljana, and most of the films seemed to have French funding. I thought, “I have to make a connection with a French producer.” Then Theodore Ushev, who’s well connected, said “I know a French producer.” He literally texted someone, who said he was interested. That was Olivier Catherin. I sent him three ideas, and he liked Roughhouse the best. Olivier wasn’t able to produce the film himself, but he passed the proposal on to Richard Van Den Boom at Papy3D Productions, who became the French co-producers of the film.

The film is an exquisite evocation of Liverpool as it was then. How did you communicate this atmosphere to your French team?

I’ve got a lot of photos and drawings from when I was in Liverpool. I actually referenced my earlier film Nightclub. I didn’t have a problem getting the animation team to understand Liverpool, because I did all the backgrounds. I kind of designed the film: the characters, the clothes they were wearing… The hardest thing was that I don’t think the team were very used to working with English dialogue. I got the feeling that most French films have very little dialogue. And Roughhouse has a lot of slang, with strong regional accents.

The accents are almost a part of the narrative. They set up the opposition between the northerner and the Brummies.

I sometimes had to explain what certain words meant. But some things were gained in translation, too. Richard and his wife Sarah Van Den Boom, who is a director at Papy3D, did the translation, and they found lots of alternatives for the F-word.

But the film is not so much about Liverpool as England in the late 1970s. It’s kind of the way people behaved and moved. I think the body language is very different from a lot of French animation. The animation acting in France tends to be a lot more elegant, stylised in a different way. I wanted something more crude and clumsy, so I showed the animators lots of live action for reference – including Alan Clarke’s Rita, Sue and Bob Too, which has some brilliant portrayals of drunk northerners.

The 2D hand-drawn aesthetic reminded me of your student films, like Dogs and Nightclub. But you hadn’t worked in that style for a while…

Around 20 years ago, everything was going digital and I was very aware of younger directors who’d grown up with computers. I thought I needed to catch up, so I started using digital software, more mixed media with less drawn animation. But I find that the older films get a better response when I show them, especially from younger people. I decided to forget about keeping up with the times and went back to drawing.

How digital is Roughhouse?

Quite a bit. The backgrounds and initial designs started out on paper. I was working in Photoshop for the colour, using hand-painted textures. It’s an attempt to look as non-digital as possible. I’ve been feeling that I should actually go back to paper, but when you’ve got used to working digitally, it’s almost scary to think about not having all the shortcuts. I’m so used to the “undo” button.

You’ve said that you don’t think of yourself as an animator.

I don’t think of myself as a good animator. Not in the way of Richard Williams or Glen Keane, or even a jobbing animator in London. I’m very slow. A film like Feeling My Way is mixed media – certainly not conventional animation.

Given your eclectic approach, what do you teach your students at Middlesex?

I do actually teach all the basic stuff, like walk cycles and bouncing balls. But it’s teaching filmmaking – things like script, editing, design, character development – that I find most interesting. There are a lot of factors involved in making a good film, and sometimes animation isn’t such an important part of that.

You’ve gone with a British delegation to teach animators in Cuba. Can you tell me more about that?

Paul Bush had been working at this film school, EICTV. It was decided that it would be good to form a sort of conference for Cuban animators, and Paul asked me to do workshops and show my work, as well as Barry Purves and [producer] Karina Stanford-Smith. The scene there is quite small and cut off. I think what they wanted was technical advice, mainly, but what they really needed was help in becoming better known outside Cuba. Technically their work is quite strong, and there’s potential for very powerful narratives; but I don’t feel that animation is really supported by the state, and this makes it very hard for independent animators to make personal films. Somehow they’ve got to start making films that get into festivals outside Cuba.

Do you keep a close eye on the animation scene?

Yeah. The student work now is staggeringly good, and I think it’s a lot harder to stand out in the crowd. When I first started out, the rough-and-ready animation I did, quite sketchy and drawn from observation, stood out. I don’t think it does anymore. You have to work a lot harder on the ideas now, because stylistically, there’s so much beautiful animation.

Changing subject: I see that your band, Cult Figures, is back on track!

I don’t know if we’re on track, but we’re back. We formed in 1977 and split in 1980 at about the age of 20. We weren’t going anywhere, and I for one wanted to concentrate on animation at the time.

You’ve composed the music to a few of your films. Some, like Train of Thought and Rug, are driven by music. Does it help an animator to be musical?

It helps me. Working in animation, you focus on timing, frame by frame. You look at time almost under a magnifying glass. The kind of timeline you’re working on is similar to a musical timeline. That’s one of the most exciting sides of animation, where sounds can trigger ideas for images and vice versa. That’s what I like about digital animation: it’s very easy to see the sound as a visual thing on a timeline, and I work with that very closely.

Finally: what are you working on now?

I’m thinking about a film about flying. I’m terrible at flying. One of the ways I start trying to deal with it is by drawing and writing about the experience while in the flight. I’m interested in how the graphics are produced for the in-flight safety cards and videos – how they’re taking any kind of edge out of what could be unsettling. But because the characters are so robotic – these androids with smiles on their faces – to me that’s part of the scariness.

What interests me in this idea is that I used to love flying when I was a kid. Somehow that changed. I’m not sure how or why. It might just be the gradual experience of life: the hard knocks and setbacks all add up.