A Talk With Independent Animator, Joanna Priestley

“I really love Flash,” Joanna Priestley gushes. “It’s so easy to use and I rarely have problems. It’s phenomenally fast, I can change things right away and rarely lose things. It’s not for everything, but it suits my style. It has totally changed the way I make films. Best of all, using Flash reminds me of what filmmaking used to be like; and once again, I can do everything myself.” This endorsement is unusual only in that Priestley, one of the leading lights of American independent animation, has traditionally relied on jerry-built techniques that seem primitive even compared to those used when Winsor McCay was starting out.

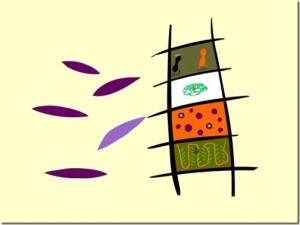

Priestley used Flash for Dew Line (2004), a delightful abstract film which she compares to “Henri Matisse’s cutout technique of his last years, which was very flat and used solid colors. But Flash is only one many techniques and I like to use many techniques.”

Dew Lines is one of two recent films — the other being Andaluz (2004), co-directed with Karen Aqua — which is included in her first set of DVD releases,Relative Orbits and Fighting Gravity. The former includes eight of her classic films, including Voices (1984) and She-Bop (1988); the latter includes Dew Lineand Andaluz, as well as The Rubber Stamp Film (1983) and Jade Leaf (1985), a rarely seen computer animated student film made at the California Institute of the Arts. Both discs also include documentaries in which Priestley describes how she works and other bonus material.

“One of my main goals in making films,” Priestley says, “is to try to push the boundaries of what I know, as far as I can. In every film, I try to do something new and different. I try new techniques, new subject matter, new styles, or new color palettes.” The one constant, though, in all her work is their deeply felt and often humorous exploration of her life and personality.

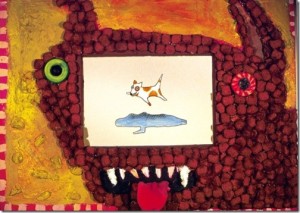

This is clearly seen in Voices, another CalArts student film which remains one of her signature pieces. She has described it as, “A humorous exploration of the fears we share: fear of the darkness, of monsters, of aging, of being overweight and of global destruction.” It features a rotoscoped image of Priestley talking to the camera, whose appearance constantly changes to reflect her fears and anxieties.

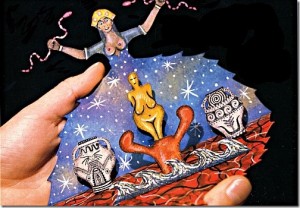

This type of personal exploration of her life is also seen in such films as All My Relations (1990) [above] and Grown Up (1993) [below], which deal with relationships and the perils of becoming middle-aged respectively. Her films also reflect a strong feminist instinct, as seen in the poetic She-Bop, which mixes puppets and drawings to examine human frailties, and After the Fall (1991), which examines the isolation of men in modern Western society. This tendency to personalize her films is even evident in her recent turn toward abstraction, including Surface Dive, inspired by her experiences diving in an underground river in Mexico.

Discovering Animation

Born and raised in Oregon, Joanna Priestley began experimenting with animation very early in her life. “One of the first toys I was ever given,” she recalls, “was a zoetrope, which worked on a little turntable and it had little zoetrope strips with it. I loved it! I’m sure I became an animator because of that toy. Then I started drawing on the corners of my textbooks in grade school, and later studied art in high school and college, where I specializing in painting and printmaking.”

After college, she moved to Paris “to study printmaking with intaglio master Bill Hayter at Atelier 17.” Returning to Oregon, she settled in Sisters, “a little tiny cowboy town in the center of the state, where there was almost nothing to do in the evenings.” With no commercial cinema around, she helped start a film society, which became a huge success.

“We then had some money left over and decided to invite Bob Gardiner, who had won an Oscar for Closed Mondays with Will Vinton. He was funny and charming and showed a whole program of animation; and that was when I really discovered animation. I immediately saw the possibilities of transferring over [from painting and printmaking] to animation. So, I went to a store, bought a pack of index cards and started experimenting with them.” It was a very inexpensive way to work which she continues to use.

Working as a film librarian for the Northwest Film Center, in Portland, enabled her to see new work and meet filmmakers like independent animator George Griffin, whose work Priestley “just fell in love with” and who became a big influence. Other animators who have had a great influence include Norman McLaren, Len Lye and Jane Aaron.

“However,” she says, “the one film that’s influenced me the most is La Jetée by Chris Marker, [which consists entirely of still photos]. I saw it in college in 16mm; I was so astounded by it that I insisted I be able to take the film and look at it myself, and was able to look at it four times in a row. At that point, I was supporting myself doing commercial slide shows with three or six projectors. And there’s such an interesting overlap between slide shows and La Jetée and animation, because movement occurs between the dissolves between these still images.”

Rubber Stamps & CalArts

In the late 70s, Priestley began work on her first film, The Rubber Stamp Film. She recalls, “It took me five years to do it. I literally knew absolutely nothing about filmmaking. I bought my own equipment from flea markets.”

The first festival she entered the film in was Telluride, where she met André Tarkovsky, “one of the directors I most admired in the world, and I just thought I died and gone to heaven. And I got a very good response to the film, including positive notices from several major film critics such as Leonard Maltin and Roger Ebert.”

Despite this success, she decided to go back to college and enrolled in the Experimental Animation Program at CalArts. “The time I spent at CalArts,” she says, “was one of the most exciting times in my life. I was worked incredibly hard and did four or five films. I was able to collaborate with my mentor, Jules Engel, on a couple of films done on the computer. It was a time when computers first arrived at CalArts, so we were the first people doing computer animation there. My desk was next to the wall adjoining the Indonesian Music Room, so all day long I would hear the gamelan rehearsing. I was also able to take African dance, study acting and stage design, helped live-action filmmakers with their projects, and did lots of wild experiments.”

“After I left CalArts,” she says, “I went back to what I had been doing. And that turned out to be extremely helpful, because what I was doing was sitting with a pile of index cards and animating away. I think sometimes when people are at a school like CalArts, which has wonderful equipment, they become paralyzed after they leave because they don’t have access to the equipment. So, lots of people don’t continue on in filmmaking or in animation. But I just went back to my studio and started working.”

On Her Own

Since then, Priestley has largely made her living making independent short films, usually depending on government funding or foundation grants to support her efforts — supplemented by workshops and teaching at the Art Institute of Portland. One of her more creative efforts at fund raising was for Pro and Con(1993), an animated documentary on prison life she did with Joan Gratz , that took advantage of a law allocating a small percentage of money for public projects to arts funding.

She had worked together with Gratz several years earlier on the joyfulCandyjam, an anijam in which 10 filmmakers from around the world did segments featuring animated candy. (The filmmakers included David Anderson, Karen Aqua, Craig Bartlett, Elizabeth Buttler, Paul Driessen, Tom Gasek. Marv Newland, and Christine Panushka, as well as Gratz and herself.)

“It was very thrilling to organize a film like that,” she said, “because what you do is put an idea out there. Joan and I had just traveled in Japan and seen all this amazing candy, which I thought, I’ve got to animate this, it’s so incredibly beautiful. But I couldn’t imagine doing an entire film with candy all by myself. So, I talked to Joan about it and the more we talked the more we thought, Wouldn’t it be amazing to ask different people from all around the world to do something with the candy from their area? So, we did and they said yes. That’s one of the really amazing things about our international community. People are very open. They’re very willing to share their talent and their time and, in this case, their money, to work together.”

In regards to Andaluz, her most recent collaboration, she says, “Karen Aqua and I started working on it when we were both, by coincidence, residents at an artists colony in Southern Spain, in the village of Mojacar. We fell in love with the place and decided to do a film about it. We had no idea what we were going to do. So, the first thing we did was go outside in a field and do a ritual, where we called to the four directions. And amazingly both of us seemed to know how to do this. It was like a miracle. You couldn’t know that about each other.”

“Out of that ritual came the idea of doing a film that would honor the landscape and the architecture and the plants and the culture of this area. That gave us the opportunity to do drawings outside and wander around the town and draw the architecture, study the plants, study the sky, go swimming and study the water. We did about 1200 drawings together.” The wonderful Moorish design motifs that populate the film, she notes, were based on tile patterns and architectural details of the Alhambra.

“The film took about four or five years to make, as a lot of things intervened: Karen was diagnosed with cancer and underwent chemo a few times, so there were a lot of emotional challenges.(She is doing fine right now.) We finishedAndaluz at the end of 2003 and released it at beginning of 2004.”

Dew Line, Priestley notes, was “based on mechanical studies I did on a trip to Alaska for the Oregon Zoo. I was impressed by an abandoned dew line station in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. All the things that were there are still there, rotting in the tundra, including thousands of rusty barrels. In photographing many of the tiny little plants found there, I began thinking of about all the species we are losing. It was also the beginning of my current interest in botany and in being a medicinal herbalist.”

Currently, Priestley has two projects she is exploring. “One,” she reports, “is a very traditional character animation about menopause. The other is experimenting with complicated collages, and putting skwigly drawings on top. I don’t know if either will result in a film. But I love experimenting and seeing where it will go. I hope the menopause film will be funny. My husband [animator Paul Harrod] thought it was a terrible idea, which made me want to do it all the more. It’s an odd subject and have been working on it for six months, I’m not sure if a film is going to happen or not out of it, but I will stay with it another six months before making a decision.”

“But,” she says, “I’ve never done it for the money. I absolutely love what I do. I love coming to my studio and am never as happy as I am when I’m working on my films.”

Relative Orbits and Fighting Gravity can be ordered directly from Priestley Motion Pictures at http://www.primopix.com/.

“I really love Flash,” Joanna Priestley gushes. “It’s so easy to use and I rarely have problems. It’s phenomenally fast, I can change things right away and rarely lose things. It’s not for everything, but it suits my style. It has totally changed the way I make films. Best of all, using Flash reminds me of what filmmaking used to be like; and once again, I can do everything myself.” This endorsement is unusual only in that Priestley, one of the leading lights of American independent animation, has traditionally relied on jerry-built techniques that seem primitive even compared to those used when Winsor McCay was starting out.

Priestley used Flash for Dew Line (2004), a delightful abstract film which she compares to “Henri Matisse’s cutout technique of his last years, which was very flat and used solid colors. But Flash is only one many techniques and I like to use many techniques.”

Dew Lines is one of two recent films — the other being Andaluz (2004), co-directed with Karen Aqua — which is included in her first set of DVD releases, Relative Orbits and Fighting Gravity. The former includes eight of her classic films, including Voices (1984) and She-Bop (1988); the latter includes Dew Line and Andaluz, as well as The Rubber Stamp Film (1983) and Jade Leaf (1985), a rarely seen computer animated student film made at the California Institute of the Arts. Both discs also include documentaries in which Priestley describes how she works and other bonus material.

“One of my main goals in making films,” Priestley says, “is to try to push the boundaries of what I know, as far as I can. In every film, I try to do something new and different. I try new techniques, new subject matter, new styles, or new color palettes.” The one constant, though, in all her work is their deeply felt and often humorous exploration of her life and personality.

This is clearly seen in Voices, another CalArts student film which remains one of her signature pieces. She has described it as, “A humorous exploration of the fears we share: fear of the darkness, of monsters, of aging, of being overweight and of global destruction.” It features a rotoscoped image of Priestley talking to the camera, whose appearance constantly changes to reflect her fears and anxieties.

This type of personal exploration of her life is also seen in such films as All My Relations (1990) [above] and Grown Up (1993) [below], which deal with relationships and the perils of becoming middle-aged respectively. Her films also reflect a strong feminist instinct, as seen in the poetic She-Bop, which mixes puppets and drawings to examine human frailties, and After the Fall (1991), which examines the isolation of men in modern Western society. This tendency to personalize her films is even evident in her recent turn toward abstraction, including Surface Dive, inspired by her experiences diving in an underground river in Mexico.

Discovering Animation

Born and raised in Oregon, Joanna Priestley began experimenting with animation very early in her life. “One of the first toys I was ever given,” she recalls, “was a zoetrope, which worked on a little turntable and it had little zoetrope strips with it. I loved it! I’m sure I became an animator because of that toy. Then I started drawing on the corners of my textbooks in grade school, and later studied art in high school and college, where I specializing in painting and printmaking.”

After college, she moved to Paris “to study printmaking with intaglio master Bill Hayter at Atelier 17.” Returning to Oregon, she settled in Sisters, “a little tiny cowboy town in the center of the state, where there was almost nothing to do in the evenings.” With no commercial cinema around, she helped start a film society, which became a huge success.

“We then had some money left over and decided to invite Bob Gardiner, who had won an Oscar for Closed Mondays with Will Vinton. He was funny and charming and showed a whole program of animation; and that was when I really discovered animation. I immediately saw the possibilities of transferring over [from painting and printmaking] to animation. So, I went to a store, bought a pack of index cards and started experimenting with them.” It was a very inexpensive way to work which she continues to use.

Working as a film librarian for the Northwest Film Center, in Portland, enabled her to see new work and meet filmmakers like independent animator George Griffin, whose work Priestley “just fell in love with” and who became a big influence. Other animators who have had a great influence include Norman McLaren, Len Lye and Jane Aaron.

“However,” she says, “the one film that’s influenced me the most is La Jetée by Chris Marker, [which consists entirely of still photos]. I saw it in college in 16mm; I was so astounded by it that I insisted I be able to take the film and look at it myself, and was able to look at it four times in a row. At that point, I was supporting myself doing commercial slide shows with three or six projectors. And there’s such an interesting overlap between slide shows and La Jetée and animation, because movement occurs between the dissolves between these still images.”

Rubber Stamps & CalArts

In the late 70s, Priestley began work on her first film, The Rubber Stamp Film. She recalls, “It took me five years to do it. I literally knew absolutely nothing about filmmaking. I bought my own equipment from flea markets.”

The first festival she entered the film in was Telluride, where she met André Tarkovsky, “one of the directors I most admired in the world, and I just thought I died and gone to heaven. And I got a very good response to the film, including positive notices from several major film critics such as Leonard Maltin and Roger Ebert.”

Despite this success, she decided to go back to college and enrolled in the Experimental Animation Program at CalArts. “The time I spent at CalArts,” she says, “was one of the most exciting times in my life. I was worked incredibly hard and did four or five films. I was able to collaborate with my mentor, Jules Engel, on a couple of films done on the computer. It was a time when computers first arrived at CalArts, so we were the first people doing computer animation there. My desk was next to the wall adjoining the Indonesian Music Room, so all day long I would hear the gamelan rehearsing. I was also able to take African dance, study acting and stage design, helped live-action filmmakers with their projects, and did lots of wild experiments.”

“After I left CalArts,” she says, “I went back to what I had been doing. And that turned out to be extremely helpful, because what I was doing was sitting with a pile of index cards and animating away. I think sometimes when people are at a school like CalArts, which has wonderful equipment, they become paralyzed after they leave because they don’t have access to the equipment. So, lots of people don’t continue on in filmmaking or in animation. But I just went back to my studio and started working.”

On Her Own

Since then, Priestley has largely made her living making independent short films, usually depending on government funding or foundation grants to support her efforts — supplemented by workshops and teaching at the Art Institute of Portland. One of her more creative efforts at fund raising was for Pro and Con (1993), an animated documentary on prison life she did with Joan Gratz , that took advantage of a law allocating a small percentage of money for public projects to arts funding.

She had worked together with Gratz several years earlier on the joyful Candyjam, an anijam in which 10 filmmakers from around the world did segments featuring animated candy. (The filmmakers included David Anderson, Karen Aqua, Craig Bartlett, Elizabeth Buttler, Paul Driessen, Tom Gasek. Marv Newland, and Christine Panushka, as well as Gratz and herself.)

“It was very thrilling to organize a film like that,” she said, “because what you do is put an idea out there. Joan and I had just traveled in Japan and seen all this amazing candy, which I thought, I’ve got to animate this, it’s so incredibly beautiful. But I couldn’t imagine doing an entire film with candy all by myself. So, I talked to Joan about it and the more we talked the more we thought, Wouldn’t it be amazing to ask different people from all around the world to do something with the candy from their area? So, we did and they said yes. That’s one of the really amazing things about our international community. People are very open. They’re very willing to share their talent and their time and, in this case, their money, to work together.”

In regards to Andaluz, her most recent collaboration, she says, “Karen Aqua and I started working on it when we were both, by coincidence, residents at an artists colony in Southern Spain, in the village of Mojacar. We fell in love with the place and decided to do a film about it. We had no idea what we were going to do. So, the first thing we did was go outside in a field and do a ritual, where we called to the four directions. And amazingly both of us seemed to know how to do this. It was like a miracle. You couldn’t know that about each other.”

“Out of that ritual came the idea of doing a film that would honor the landscape and the architecture and the plants and the culture of this area. That gave us the opportunity to do drawings outside and wander around the town and draw the architecture, study the plants, study the sky, go swimming and study the water. We did about 1200 drawings together.” The wonderful Moorish design motifs that populate the film, she notes, were based on tile patterns and architectural details of the Alhambra.

“The film took about four or five years to make, as a lot of things intervened: Karen was diagnosed with cancer and underwent chemo a few times, so there were a lot of emotional challenges.(She is doing fine right now.) We finished Andaluz at the end of 2003 and released it at beginning of 2004.”

Dew Line, Priestley notes, was “based on mechanical studies I did on a trip to Alaska for the Oregon Zoo. I was impressed by an abandoned dew line station in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. All the things that were there are still there, rotting in the tundra, including thousands of rusty barrels. In photographing many of the tiny little plants found there, I began thinking of about all the species we are losing. It was also the beginning of my current interest in botany and in being a medicinal herbalist.”

Currently, Priestley has two projects she is exploring. “One,” she reports, “is a very traditional character animation about menopause. The other is experimenting with complicated collages, and putting skwigly drawings on top. I don’t know if either will result in a film. But I love experimenting and seeing where it will go. I hope the menopause film will be funny. My husband [animator Paul Harrod] thought it was a terrible idea, which made me want to do it all the more. It’s an odd subject and have been working on it for six months, I’m not sure if a film is going to happen or not out of it, but I will stay with it another six months before making a decision.”

“But,” she says, “I’ve never done it for the money. I absolutely love what I do. I love coming to my studio and am never as happy as I am when I’m working on my films.”

Relative Orbits and Fighting Gravity can be ordered directly from Priestley Motion Pictures at http://www.primopix.com/.