Mars Express | Interview with Jérémie Périn

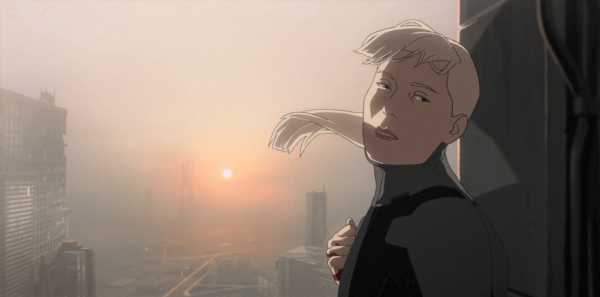

We need more films like Mars Express. Jérémie Périn’s debut feature is an original sci-fi animated feature with a complete view of a future where humanity and technology have begun to fuse into one. Unlike the droplets of original sci-fi we get from Hollywood, Mars Express has a consciousness of the political and existential responsibility of sci-fi storytelling. This dystopian view of a future Martian society is a stone’s throw from our current landscape of human rights infringements and culture wars that are stoked to fuel corporate agendas.

Resting upon the inherently cinematic detective story, Mars Express embeds us in a moral quandary surrounding the freedoms of robots. When a girl known for illegally jailbreaking machines – giving them a chance to overcome their programming – goes missing, it falls on PI Aline Ruby to solve the case. While many detective stories act as a way to reinforce the virtues of the law, Mars Express sees its protagonists forced to question their morality. This is especially true for Ruby’s cyborg partner, Carlos Rivera, a robot with the consciousness of a late human, who has to question a society that represses his own kind.

Skwigly caught up with Périn over Zoom to discuss the political foundation of his film, the technological design of this society and making animation on a budget.

Could you talk about where the idea for Mars Express came from?

I always wanted to do a sci-fi movie one day. I tried to create a sci-fi TV show first and then pitched some movies, but every time it failed. Some producers were interested but in the end it didn’t happen. It was a different time. Adult animation was not a thing in France, it was more difficult to do and it’s still difficult today. But I directed a TV adaptation of comic books called LastMan, which was for teenagers and adults and it became a success in France. This brought me the opportunity to do whatever I wanted after that, so I finally made a sci-fi movie. In the field of science fiction, you have many possibilities and we wanted to do some hard sci-fi, something more logical, more scientific, more pragmatic, more realistic. Sci-fi movies at the time were more focused on something I would call magical sci fi, like, Star Wars or in those Marvel movies and stuff like that.

What I like in sci-fi is the opportunity to talk about our present. To talk about political ideas but in a metaphorical way, to push the boundaries of the technologies to talk about the technologies already around us and what they say about us. At the time there were also those tech billionaires talking about leaving Earth to live on Mars or in a space station. I won’t hide it, I’m on the opposite end of the political spectrum to those tech billionaires. So, I wanted to be a bit satirical about that way of ruling society that they have in mind. I, alongside my co-writer Laurent Sarfati, wanted to imagine what it could be like to live on Mars in a society built by that kind of libertarian billionaire. That’s why in the movie you have no trace of any political people. There’s no mayor, there’s no president, it’s just corporations.

How did you go about designing the technology of the film? There’s laptops and phones but also more unfamiliar pieces of tech.

We wanted to have different kinds of technology living all together. We wanted to express that some robots are older than others, so I hired different designers for the robots, just to feel that it’s not the same person who built everything. Also, when you’re out in the street, every car around you comes from a different company, so we try to replicate that on a smaller scale, of course. All those mixed technologies are also there to express this feeling of a more natural society organised with different companies and possibilities of design. And the fact that Carlos’ head is a hologram comes from that. It was something we had in the script that Carlos’ body is an older model compared to many other robots in the movie, and so I had this idea of making him a standard body and his only originality is in his face. It’s like your profile picture on your Facebook page, you know, all Facebook pages look the same except for your own picture. Also, usually in movies, when you use a hologram, after five seconds the hologram is glitching for the audience to understand, it’s a hologram. And I was like “No, it has to actually work!” There’s no glitch. It’s a little bit transparent, and he has a head separated from his body, it’s like a ghost. So, it’s a way of telling his own story visually.

The film takes in a lot of influences from classic sci-fi and video games and anime. How do you balance absorbing those influences and avoiding tropes?

I try to trust my feelings. Some tropes are really interesting because you can use the expectation of the audience. If you succeed in using a trope, but right after you’re twisting it, it’s okay to me. So it depends on the effect you need to have in your sequence. But sometimes I know I’m in a cliche but I don’t have a better idea. Sometimes you let it go. I try to think about the tropes as an audience member, like, if I watched that in a movie, would I be annoyed by it? It’s more of a feeling.

There’s a warmth from that familiarity and sometimes you rely on those tropes for worldbuilding.

Yes. I don’t really like to wink at the audience, it has to mean something when you do some references. In the movie, there are some quotes, but they are more for the audience to understand the situation.

People often talk about the limits of 2D animation, but Mars Express feels uncompromising in its dynamism. How did you achieve that?

Well, sometimes the background is in 3D, so we mixed the techniques. And in the beginning, it was more to express having, on one side, humans that are hand-drawn, and, on the other, robots that are made by machine. There are still people behind the computer to model them and to animate them, but the rendering is manmade for the humans, and the robots are rendered by machine. I thought that idea was funny. At the same time, I knew we would have cars and robots in 3d, I was like, yeah, sometimes we could have the background in 3d. As an example, in the car crash scene, all the background is in 3D because there were so many cars in it, it was more simple to do it all in 3D, just to have the cars in the right perspectives. As I knew I would have a 3D background, I knew I could do some camera movement and play with depth. I knew while reading the script that a 3D background would be more efficient.

What’s the secret to maximising a small budget to tell a grand story?

We had to cut some scenes, we had to shorten some sequences and stuff like that. In general, animation is expensive, let’s say that the minimum of an animation movie budget is higher than live action movies. But at some level, it’s the same to tell a story in a kitchen as in a spaceship, because it’s just drawings. It’s not exactly true, because you have to design most sci-fi movies, but in live action, the movie would have been way more expensive, especially in France, it would never have been possible to make it. Also, I grew up with Japanese animation which was full of tricks to make it bigger than it is. So I used a lot of the tricks I analysed on those animated features. And also, the way we are making our movies in France, and I guess it’s the same in Japan, but we have this ‘poor people methodology.’ We know that we won’t have a big budget, so we structure our way of making movies differently than you would for DreamWorks or Pixar or Disney movies etc. I think when you have a big budget, I think you can easily throw away some shots or make them twice or three times and go back to script while some shots are already rendered and stuff like that. We can’t do that. We have to be very sure about ourselves before going to the next step.

Mars Express is out in cinemas across the US today, for info and tickets visit gkids.com and keep your eyes on Skwigly for future news of the film’s international distribution.