Japanese Animation: East Asian Perspectives – Book Review By Harvey Deneroff

Japanese animation, with its huge worldwide fan base, does not exactly seem to be crying out for yet another book. But Japanese Animation: East Asian Perspectives, edited by Masao Yokata and Tze-yue G. Hu (University of Mississippi Press) attempts to explore new and unexpected territory, at least in English. The essays, by East Asian scholars, grew out of Tze-yue’s preparations for her book, Frames of Anime: Culture and Image-Building (2010) and the activities of the Japanese Society for Animation Studies. (I should admit I wrote an endorsement for Frames of Anime and Tze-yue also mentions me in Japanese Animation for my role in starting the Society for Animation Studies.)

Like many anthologies, it’s something of a mixed bag and the quality of the writing and translations are occasionally wanting. Nevertheless, I found a number of the articles fascinating, sometimes surprisingly so. For instance, Dong-Yeon Koh’s “Growing Up with Astro Boy and Mazinger Z,” is an exploration of how anime was received in South Korea, where it was officially banned for many years; for instance, she argues that the Korean government used Astro Boy to further its policies in the 1970s and 1980s, including promoting rapid industrialization and technological innovation, as well as anti-North Korean propaganda; the latter was not intended by Tezuka, but, Dong-Yeon couldn’t resist pointing out that in the second Astro Boy series (in colour), the evil “Count Walpurgis … was depicted in red … [and] the color red must have been perceived as the unmistakable symbolism of communism to most South Korean viewers….”

Tezuka is the focus of several other essays, including Makiko Yamanashi’s “Tezuka, Takarazuka: Intertwined Roots of Japanese Popular Culture.” In it, Makiko explores how the God of Manga found inspiration in his home town’s all-female theatrical revues, which she argues was the inspiration for Tezuka’s coming up with the shōjo manga (manga for girls) genre with Princess Knight, and the anime series that followed.

Another paper dealing with gender issues is Akiko Sugawa-Shimada’s “Grotesque Cuteness of Shōjo: Representation of Goth-Loll in Japanese Contemporary TV Anime,” which examines gothic-Lolita girls in Jigoku Shōjo (Hell Girls) and Death Note. Sugawa-Shimada’s discourse on this odd (to Western eyes) combination of masculinity and femininity are “linked to postfeminist gender-free (gender-equality) movements.”

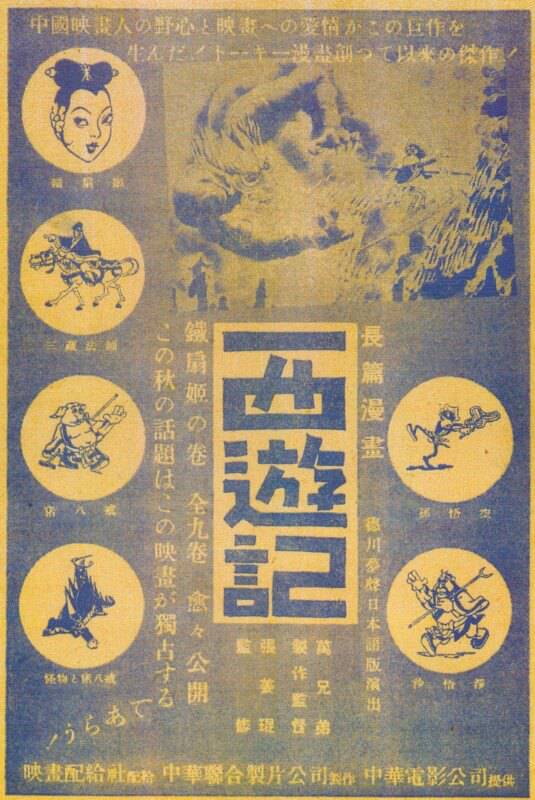

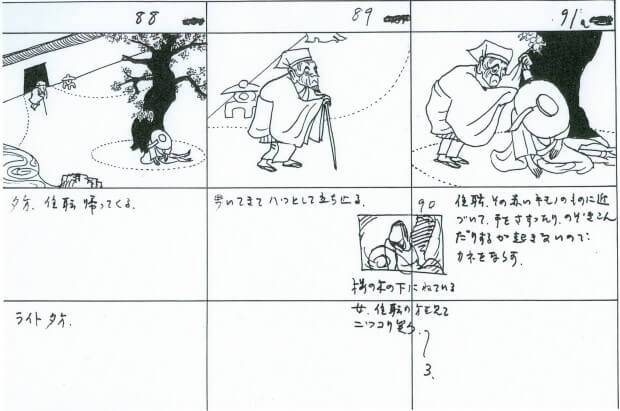

In “Reflections on the Wan Brothers’ Letter to Japan: The Making of Princess Iron Fan,” Tze-yue expands on her exploration of the first Chinese animated feature in Frames of Anime. Iron Fan (based on Journey to the West) was obviously made as a rallying cry for China’s warring factions to unite against the Japanese invaders; yet it was successfully imported to Japan, where the film was a “dai shokku (big shock). They found it unbelievable that a war-torn and occupied China … could complete such a dedicated film project.” It also seems to have had a major impact on Japanese animation. (The letter, in which the Wan Brothers explain how they made their film, was published in the December 1942 issue of Japan’s Eiga Hyōron.)

Masao Yokata, a professor of psychology, provides a discourse on “Animation and Psychology: The Midlife Crisis of Kawamoto Kihachiro,” Japan’s best known puppet filmmaker. Yokata asserts that Kawamoto’s decision to give up his career to study with legendary Czech animator Jiri Trnka, so he could begin a career as an independent filmmaker, is a classic case of a midlife crisis in action. He also points out that a number of other directors, including “Takahata Isao, Miyazaki and Oshii Mamoru … [changed] their themes in animation according to their life cycle.” However, most of the essay is devoted to analyses of Kawamoto’s films, including some unfinished ones.

Then there is Hiroshi Ikeda’s “The Background of the Making of Flying Phantom Ship,” in which the director discusses the context in which he made the film. He talks about the influence of Italian Neorealist films on postwar Japanese live-action films, especially those produced by Toei Film Company, whose animation unit made Flying Phantom Ship (1969). The latter, along with the earlier Prince of the Sun: The Great Adventure of Hols (aka The Little Norse Prince) (Takahata Isao, 1968) “had … strong sociopolitical message[s],” which were not well received at the box office; thus, his attempt to turn Animal Treasure Planet (1971) into a commentary on international political issues was abandoned. However, the drive to make animated movies more socially relevant and more appealing to an older audience would be continued by Takahata, as well as Miyazaki, who were “the key production members” on Phantom Ship when they subsequently left Toei “to make animated works with social messages and aspirations, this time bringing critical value to the medium of animation in Japan and worldwide.”

These and other articles in Japanese Animation help elucidate some of the little known nooks and crannies of anime, which I suspect will interest more than just the most dedicated otaku.

Items mentioned in this article: