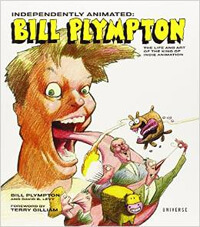

Independently Animated: Bill Plympton – The Life and Art of the King of Indie Animation

Animation, like many creative industries, is one plagued by procrastination – it seems everyone has a film in them, one about which they will talk endlessly yet never put the energy into making a reality. Against that backdrop, Bill Plympton should be everyone’s hero. What makes his success so deserved is that his story, as told in “Independently Animated”, is a perfect case study of the consequences when an individual puts the same amount of energy into doing as most do into merely pondering the possibilities.

Animation, like many creative industries, is one plagued by procrastination – it seems everyone has a film in them, one about which they will talk endlessly yet never put the energy into making a reality. Against that backdrop, Bill Plympton should be everyone’s hero. What makes his success so deserved is that his story, as told in “Independently Animated”, is a perfect case study of the consequences when an individual puts the same amount of energy into doing as most do into merely pondering the possibilities.

In all likelihood you’ve encountered Plympton’s work in some form or other, from his frequently-aired shorts such as “Your Face”, “How To Kiss”, the “Dog Days” series et al – which casually incorporate shameless carnality, violence and unexplainable visuals reminiscent only of hypnagogia and drug/fever- induced hallucinations – to his commercial work on music videos and television adverts (mine is a generation plagued by nightmares of two corpulent businessmen debating the more endearing characteristics of Nik Naks). Animation enthusiasts may even know him for his feature films, or as ‘the guy who turned down Disney’. Whichever it may be, his style, knack for timing and sense of humour is instantly identifiable.

A book which systematically covered his filmography would have been satisfying enough in itself – where the real heart of this lies is its autobiographical nature and sense of humour, going into enough detail on his geographical and stylistic origins to be enlightening while steering well clear of ponderous or self-indulgent. Worth noting is David B. Levy’s co-author credit, which likely contributed significantly to the structure of the writing; having established himself as an author on many aspects of animation by this point, his similar attitude, ethos and pro-activity both within the industry and as an independent make him an ideal co-scribe (also warranting a nod is the introduction by Terry Gilliam, which in its purposeful redundancy sets the tone perfectly).

Having hailed from Oregon, Plympton warmly documents the trajectory of a career that begins, naturally enough, in childhood doodling, to illustration and comic strips in his early adulthood, making do in an era where the animation industry was hopelessly stagnant. By the time the book reaches the familiar territory of his more widely known work, we’ve already learned considerably more about his motivations and influences – artistic, familial and political.

The inside information on his films and industry work is, to the Plympton fan, a joy, and it would be hard to imagine it as much less to the uninitiated. Told with surprising candour are the stresses and satisfactions of making animation with minimal resources, budget and crew, while remaining consistently inspiring. Recounted celebrations and career milestones are balanced out with recollections of nightmare screenings and lamented missed opportunities. Any illusion that it’s an easy life is permanently extinguished, but in terms of personal contentment it makes a compelling case.

The presentation of the book itself is fantastic, bulked out by beautifully reproduced artwork spanning examples of his early artistic endeavours, paintings and satirical comic strips to storyboards, character designs, layouts and film cels. One could take it equally as a thoroughly annotated art book or as a definitive illustrated biography; either way it delivers. Its flaws are largely superficial, in that the text could have benefited from a more thorough comb-through in the proofreading stage, or that possibly some of the longer sections of artwork-only pages seem to be thrown in randomly, interrupting the flow – one might be in the thick of a particularly engaging anecdote only to find they can’t help but be suddenly distracted by the meticulously-sketched opening act of one of his films for twenty-odd pages.

To a reader unfamiliar with Plympton’s full body of work, there are passages that could conceivably come off as vainglorious when referring to the positive responses, accolades and income his successful films have garnered. What counters this, however, is his humility and respect for his peers and contemporaries alike, acknowledging the wealth of genius the independent scene has to offer and taking inspiration from it. For instance, he reveals that it was the work of PES among others that motivated him to up his game with the Oscar-nominated “Guard Dog” and not settle for a creative plateau.

Equally appealing is his affection for projects that did nothing to enhance his career, sometimes even stymieing it such as a string of live-action features – previously unbeknownst to this reader – which led to financial and commercial dead-ends. As easy as it might be for some filmmakers to recount these setbacks bitterly, this is a man clearly more driven by the impulse to acknowledge that failures and successes are equally as critical to creative growth.

What’s most encouraging is that we’re left with the distinct impression that these aren’t the remembrances of a man at the end of his career, or even at the midway point. He speaks with the same caution-tinged enthusiasm for what lies ahead as what’s already come to pass. As laudable as his back-catalogue is for quantity and quality, it’s entirely possible that his magnum opus is yet to come.

Items mentioned in this article: