How to THINK When You Draw – An Interview with Lorenzo Etherington

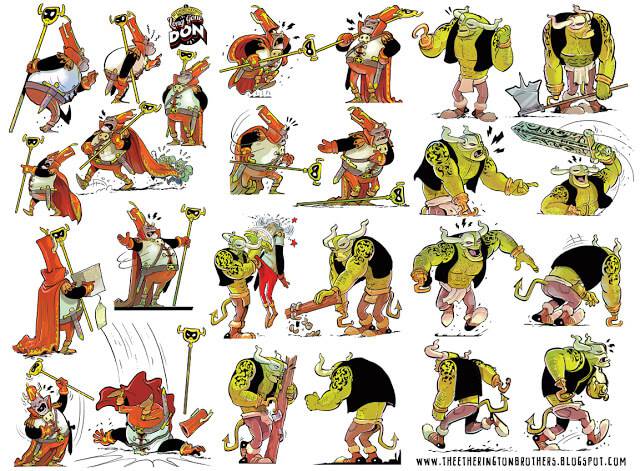

Lorenzo Etherington brothers is best known as the drawing half of UK comic superstars The Etherington Brothers. Alongside his writer brother Robin they have created work for comic clients such as Yore for The Dandy, Von Doogan for The Phoenix and Monkey Nuts for The DFC as well as working for Disney, Dreamworks, Aardman on their properties.

Lorenzo Etherington

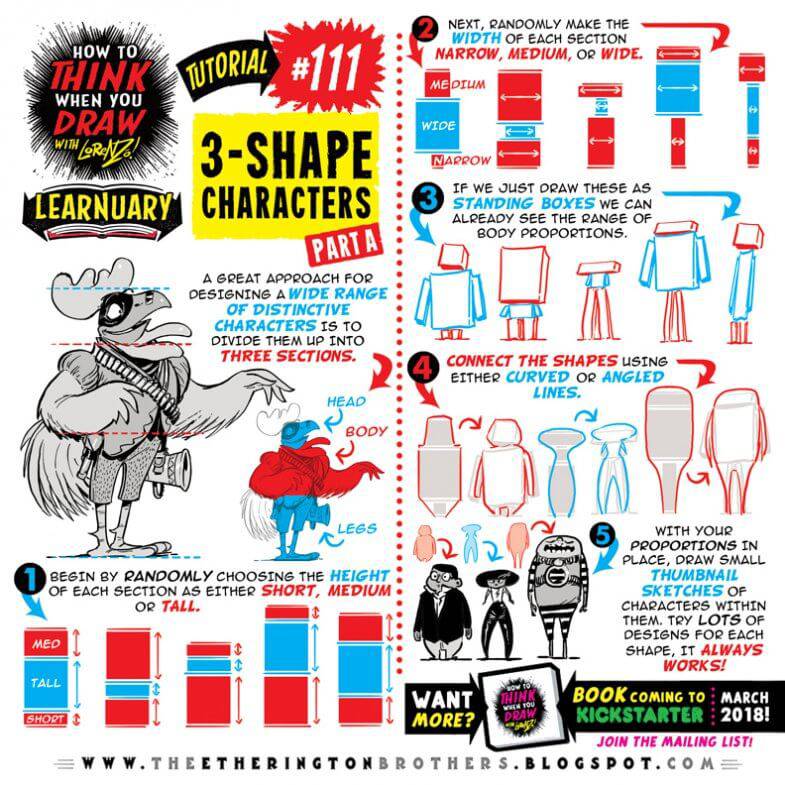

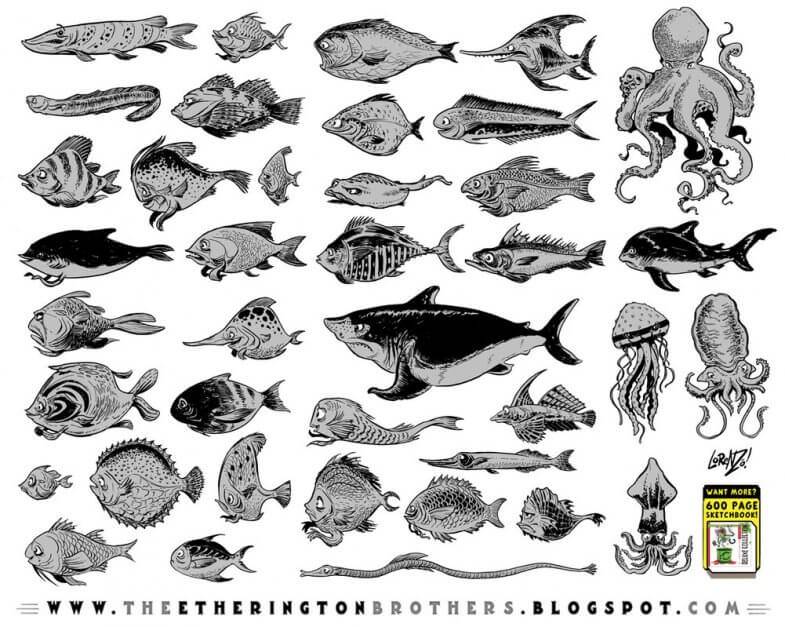

Keen to share his drawing tips and secrets with a wider community Lorenzo also produces a series of free online tutorials called How to THINK when you draw, an invaluable resource for comic artists and animators accessible to beginners and professionals alike and everyone in-between which gives those reading a chance to apply these principles to their own work. These lessons have recently been compiled into paper form for those who prefer a more tangible read which is available for a few days via kickstarter the campaign has already raised over a quarter of a million dollars, and finishes on Friday April 6.

We caught up with Lorenzo Etherington to find out more about his drawing habits, clients and how he thinks when he draws!

You’re primarily known as an illustrator alongside your brother Robin who writes, how do the Etherington Brothers work as a team?

We have a very clean divide between words and art – no crossover! One the most amazing things about working with my bro all these years is the shared experiences and interests we had when we were kids have given us an intuitive creative process – he knows what I love to draw, and I know what he loves to write! Robin begins all our stories with a screenplay-like script, which comes to me to rough the pages, and then back to him for lettering and editing, and then back to me for final art!

Your comic clients include UK mainstays The Dandy and The Pheonix, who influenced your comic creations growing up?

I was influenced by creators such as Bill Watterson (Calvin and Hobbes) and of course Albert Uderzo (Asterix), both of those artists gave such love and care and life and JOY to every frame of their comics. The tone, the endless feeling of movement and personality, it’s in every little detail of those series.

You’ve also worked on animated properties for Aardman, DreamWorks and Disney, can you tell us much about these projects?

We’ve actually created a lot of comics for Disney, Dreamworks and Aardman, working on franchises such as Transformers, Star Wars, How to Train Your Dragon, Kung Fu Panda, Wallage and Gromit, etc. We’re also working with studios developing our own series for animation, though we can’t talk about that stuff at the moment! The hardest thing for creators is always understanding when to compromise and when to stick to your vision. Understanding what the core ingredients of a story or world are, that HAVE to be in the animation, and which elements are open to adaptaiton as part of the creative transition from page to screen is key. Never be afraid to walk away if a studio or publisher is trying to push your creation to a place that doesn’t fit anymore. Your vision is your vision, value it.

Can you tell us more about your personal project Stranski?

Stranski is an art project based around a fictional “lost” animated film from the 1940s. All the artwork for the project is presented as promos and ephemera relating to the film, though the actual detail of what the film was, who created it, or just what it was about remain a mystery. It’s an on-going labour of love for me, and an experiment in telling a story through disconnected vignettes and moments. It’s certainly better seen than described!

Is there much of a crossover between the way you think whilst creating comics and the way you think when animating?

The two processes, in terms of storytelling, are almost identical. Framing, direction, character arcs, performance, sense of place, story timing, dialogue, it’s all the same set of skills. A comic is really just a set of key frames. When comics feel dead and lacking in movement it’s because the creators have forgotten to think as animators. A comic has the luxury of keeping our attention by jumping continuously to the important moments. Animators can learn from this process too, to help keep the pacing on-point with the plot and the central energy and movement of the world and story.

Is there a reason you’ve made these tutorials available for free?

I watched with disappointment as the advent of sites such as Patreon, Gumroad and paid online courses locked most of the very best online art teaching away behind paywalls. While I think it’s AWESOME that artists can make money from sharing their skills, that doesn’t help the millions of artists who can’t afford these services. I decided I’d create FREE drawing tutorial series so massive, and so diverse, that artists will never have to pay to learn to draw again. And with my #Learnuary initiative, I’m trying to encourage other creators to do the same, and start giving some skill sharing back for free. The response to the series has been incredible.

You’ve already created two 600 page sketchbooks and you’ve compiled another as part of this kickstarter campaign, that’s a lot of work, what’s your working day like and how many drawings do you usually get through?

My working day is all about discipline and routine, which sounds boring and unartistic, I suppose, but I’ve found that this is the way to tap into your most productive form of creativity. I get up and get to it, doing some warm up sketches and life drawing practice for the first 40 minutes, then into working on a tutorial, then some designs and concepts just to keep my imagination trying new things. Then I go into the work of the day, which is often something like Stranski or one of my other projects or comics. I do pretty long days, but by switching between projects throughout the day, it always stays fresh for me, which is the secret to keeping the joy in your creativity, I think!

You can keep up to date with The Etherington Brothers on their Blog, Website, Twitter and Instagram and donate to the Kickstarter campaign (until the 6th April 2018) here.