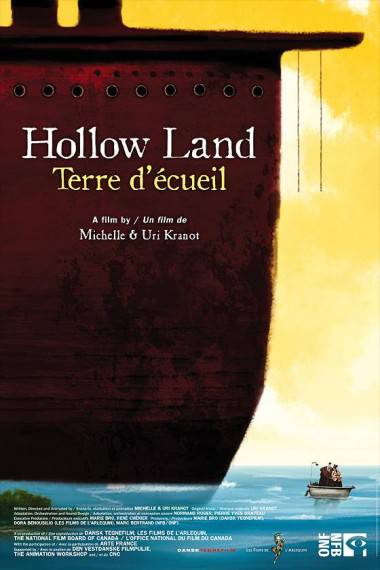

Interview with ‘Hollow Land’ co-director Michelle Kranot

An international co-production between Denmark, France and Canada, Michelle and Uri Kranot‘s Hollow Land stood out as one of 2013’s more thought-provoking animated shorts, for both its unique stop-motion approach and compelling tale of a wandering couple eager to call the strange land in which they’ve wound up ‘home’. Despite the promise of an idyllic way of life, Solomon and the heavily-pregnant Berta soon find that the regimented environment they now inhabit is far from comfortable; Beneath the surface it is oppressive, claustrophobic and hostile.

An international co-production between Denmark, France and Canada, Michelle and Uri Kranot‘s Hollow Land stood out as one of 2013’s more thought-provoking animated shorts, for both its unique stop-motion approach and compelling tale of a wandering couple eager to call the strange land in which they’ve wound up ‘home’. Despite the promise of an idyllic way of life, Solomon and the heavily-pregnant Berta soon find that the regimented environment they now inhabit is far from comfortable; Beneath the surface it is oppressive, claustrophobic and hostile.

The film marks the fourth collaborative project between Michelle and Uri, themselves a married couple who have striven to maintain their work as sympatico creatives, following on from 2005’s God On Our Side, 2008’s The Heart of Amos Klein and 2010’s White Tape. Venturing into puppet animation while holding onto their 2D roots has given Hollow Land a particularly endearing visual style which lends itself perfectly to a narrative both surreal and foreboding, yet ultimately accessible, relatable and peppered with moments of levity. Recently co-director Michelle Kranot took some time to discuss the film with Skwigly.

The film’s production was impressively spread over three countries. Did you find that the international approach of spreading the film’s production over three countries served the film well?

Uri and I are based in Denmark and most of our success has been in Europe rather than North America, so we’ve been very lucky to work with the NFB. Marc (Bertrand) has been our NFB producer and had a lot of input as far as both the script and the technique were concerned, he’s been really supportive when there were issues between countries, so as far as I’m concerned Marc’s the man, he really took care of us and our production. So in that sense it’s been an NFB film, though not a strictly NFB film because it’s this international co-production. We have made a number of films with our French producer Dora Benousilio who has always supported our artistic vision. Our Danish Producer, Marie Bro has worked and continues to work hard on behalf of our film. We enjoy the co-production collaboration very much and plan to continue to work together in the future.

Did most of the animation take place in one country?

We physically made most of the animation in Denmark as part of the Animation Workshop, which is an artist in residence programme (where we’ve been residing) and also a school where we both teach.

The Animation Workshop has a pretty strong reputation for high-quality output, does it have a particular approach that sets it apart from other institutions?

I think so, for many reasons. First of all there’s a guest teacher system, potentially what happens is you get a teacher coming in for two weeks at a time, doing a single project with the students. Then they get top professionals from around the world who leave their job and their families for two weeks and come and teach. So you get very engaged teachers who are at the top of their game and are actively doing what it is they’re teaching. The other thing is that it’s a very warm, vibrant, international community, so people are very dedicated to it. Obviously there’s a lot of focus on the quality of the work and as it’s small-town, middle-of-nowhere Denmark basically all they can do is work! There’s also a lot of focus on what kind of people they are. It’s a very holistic education but they’re training people for the industry, some filmmakers who are directors are encouraged to do what they do, but really they’re training people to work in studios. I think they do that very well. The thing that makes it unique are the internship placements, people in their final year get really good internships and often get hired, so it’s not just another school that teaches you things, it’s actually a part an industry. The Animation Workshop is a school, but it’s also a small business cluster, so people are encouraged to leave school and set up their own companies. I think that’s what makes it special, that and they’ve got great parties!

Hollow Land (Michelle & Uri Kranot, 2013)

Another thing which is quite nice about the film being produced internationally is, in a way, the theme of the film itself and the potential hostilities associated with immigration and cultural clashes. Was that a component of the story that helped sell it as an international co-production?

That’s a good question, I think that in the beginning, in terms of selling it, when we were pitching it as a story about immigration our producer loved it, it was that first pitch that sold it. But it evolved to be a story that isn’t necessarily about immigration, and I think that what makes it strong is that it’s not a story about relocation, it’s a story about displacement in general, about a relationship; It’s a very human story that isn’t necessarily categorised as political or geopolitical, which many of our previous films are. Where I come from I’m considered an extreme political filmmaker, but this one is different. I don’t think we’re using immigration as a selling point and I don’t think that’s why it’s successful, I think it’s successful because it speaks to people on a human level and also, to be perfectly honest, I think the technique is refreshing. I think it stands out in that sense. And yes, our personal experience of moving country to country has a lot to do with the story, and we were moving from country to country as we were making the film.

Had there ever been friction or opposition when travelling to different places, either for yourselves or your family histories?

Well, every generation in our families – as far back as anybody can remember – has immigrated, so no-one ends up where they were born. Our families came from Eastern Europe but every generation’s had to pack up and leave and start a new life. I don’t know what’s going to happen with my kids, but I find it rather hard to believe they’re gonna spend the rest of their lives in small-town, middle-of-nowhere Denmark.

Hollow Land (Michelle & Uri Kranot, 2013)

With the way the film begins where the couple arrives in this new land, there’s the suggestion of hope, or at least “this’ll do” before they have to face all the compromises that come with their new way of life. Was the theme of hope a major consideration in writing the story?

I think we all have hope, but more specifically we were very much inspired by immigrants to Israel who were told that they were going to be located in Tel Aviv or Jerusalem or someplace wonderful that looks like a postcard. That was what everyone was selling them, “Leave wherever you are and come to Utopia” where they found that it was just sand and desert, and they were mistreated. It wasn’t the life they wanted, necessarily, or better than where they left. So that was a direct inspiration, that this couple come looking for Utopia and find themselves up to their necks in sand. But everyone, when they make a change in their life, hopes for the best, and makes adjustments. Nothing’s perfect but, hopefully, nothing’s horrific either. I mean, we’re not portraying a holocaust, we’re not portraying people who are going through atrocities, they’re not escaping from something so horrific that they don’t have a choice, they made the choice to not stay where they were, but it’s not an easy choice to make.

What I’m also curious to know about is how Uri and yourself came together, having worked on so many projects together in the last few years…

We met at Annecy where we both had films in the student competition – we’d gone to school together but didn’t actually know each other. Then we stayed together and we’ve been together for twelve years since. I always knew that if I was going to be with anybody he’d need to understand that I make films and that’s a priority, and I think that he felt the same and the connection that we could make films together was kind of ideal, because animators move around, we go where the funding is or where there’s another opportunity. We’ve never had conflict over where should we live, or how should we live, we don’t have clashes of our priorities – I think we’re pretty lucky!

It’s especially good that you’re able to function as a creative partnership also.

Well, one thing we can avoid is stagnation; It never gets boring, we never stop working and there’s always somebody to tell you “This is good, you can move ahead” or “You’ve gotta do this again, because it’s not as good as it can be”. So we trust each other and we’re very critical towards each other but it’s always in a constructive way because we move forward, we’re constantly progressing. Even though it can takes years to make a film it’s always interesting, it’s always challenging, because we’ve got each other.

Are there areas of production one of you will gravitate toward more than the other?

Most of the films we work completely together, as with Hollow Land – we wrote the script together, we directed the film together, we did the storyboard together. But when we finished the storyboard Uri did the actual layouts, we designed the characters together but I painted them, we really shared the work between us, and we also share our lives. I think today we don’t know who animated what, which is true about our previous films as well; We did it all together, it’s very symbiotic. But there’s always a lot of space for doing our own thing – I pushed for some things that were a lot more experimental, while Uri has a very cinematic approach, and is very good at things like perspective, which is something that I don’t really get. Uri has his own realm where he writes the music for our films, he plays all the instruments himself but when they do the final mix he gets all kinds of other musician friends to come and play. He composed the music but Normand Roger arranged it, I think they had a beautiful thing going there. Just the other day when he was editing a ‘making-of’ I got to see them in action and it was obviously an outstanding experience. Another thing that’s very lucky about the Animation Workshop is that they have the facilities but also the talent, so the tech guy is also a master musician who can play the piano; You can pull all sorts of people out of their little holes and you get a band, eventually.

A big issue for filmmakers is getting the right music for their work, so if a director also has that musical ability and approach it’s a big help, I’m sure. From your perspective does Uri approach making music from a similar angle to animating, as a creative process?

First of all, the music for all our films isn’t something that comes later, it’s part of the same creative process as writing the story, designing the backgrounds and timing it. Another thing that’s important about animation is that if you get the timing right, one of the hardest things is to put the music on top after. The music is an integral part of the piece, in our case we usually do it before, at the animatic stage, so before we actually animate it we already have a good reference guide for what the music is going to be like.

As you were saying earlier, it’s refreshing to see something in an established medium that feels different. The unique take on stop-motion Hollow Land makes use of seems as though you’ve taken the layering approach used with most modern 2D animation and applied it to stop-motion puppets.

That’s exactly what it is, yeah.

How did you hit upon that technique?

Well, we’re traditionally 2D animators. We’ve worked with cut-outs before and we knew we wanted the immediacy of that medium, but not to work with so many layers under the camera. So in Hollow Land they’re all flat puppets shot on glass. There was a blue screen behind them which we keyed out and composited all the background elements digitally. We were both very much inspired by puppet theatre and shadow puppets and to me what was important was to play with the illusion of depth. We wanted to create a space that would be challenging, to work with totally flat pieces composited as though it was 2D to give it an edge. This is sort of a new technique as far as I’m concerned, but it’s really based on traditional animation and traditional fine arts. So we were making a 2½D film where every shot was important. You need to keep yourself interested in actually making it once the script and animatic is done, so the making of it was challenging because every shot was tackled afresh, “How do I play with this illusion of depth?”

For the film’s epic Colosseum sequence the animation switches to a more conventional 2D hand-drawn animation. Why did you choose such an extreme style shift for that particular scene?

In all our films we’ve experimented with different techniques within the same film, I think in this case we actually wanted to create a scene that was surreal and have it be out of time and space. The normal environment of what you’ve learned to accept is this 2½D puppetry, then the hallucinatory state or the subconsciousness is something that is actually a technique that you’re used to seeing. It’s 2D, pencil-on-paper, a medium I feel very comfortable with, it allowed a lot of freedom in terms of what kind of movements it could make, how the water was gushing and all kinds of things that this type of animation really allows you to do. While puppet animation is so restricted by the puppets – which is something I found interesting – 2D animation has no restrictions in terms of what kind of movements you can make. I wanted it to be in-depth but also approachable, to me this Colosseum sequence is this vital moment where this couple are battling it out, they’ve been struggling with each other and this is when it explodes, and they’ve been pushed to that. It’s the most political sequence to me and is the essence of the film. If I had to describe the film in one word it would depend on who I spoke to, but to my Mother I would say “Conformism – and all you have to do is watch this sequence to know why”. You conform to the expectations of society in general, and women are subjected to losing control over their bodies, they’ve been culturally conditioned to do so. It doesn’t have to be bands of men screaming at you but sometimes it is.

Hollow Land (Michelle & Uri Kranot, 2013)

Now we’re at the stage of the film being out there and quite visible, being shortlisted for the Oscar nominations…

We’re in the top ten!

It’s a pretty good place to be.

To me it’s shocking and wonderful at the same time, especially wonderful because everybody who doesn’t know anything about animation knows what the Academy Awards are. It’s a big deal, especially in North America. It’s less of a big deal in Europe, actually, but it means an awful lot to our family and our producers. I’m very proud to be among those people listed because there are some fantastic films up there, some of my favourite films I’ve seen are up there so we’re in very good company. I’m feeling very humble by the whole thing, actually.

Are you busy with other projects at the moment or has the success of Hollow Land taken over for the time being?

We shot a ‘making-of’ for Hollow Land, so we’ve been editing that and reviewing the pieces and putting it back together. Something we’ve kind of toured with it a little bit and now are taking further is a Hollow Land Experience. It’s an installation performance that’s based on the film, basically we’ve extracted the characters from the backgrounds and environments, we give our audience masks of the main characters and we put them in the same situations. It’s not necessarily linear, we put them through Berta and Solomon’s journey and they get to watch the film having been in the middle of that Colosseum with all those people screaming at them. It’s also an exhibition installation where bits of the film are projected on objects, from within objects, the elements from the films. We had thousands and thousands of pieces, so we decided to do something constructive with them, make it beautiful and show it to the public.

We’re also doing a lot of other projects, Uri and I both teach and are running a course starting soon for EU participants called AniDox that puts together animation and documentary filmmakers to work on collaborative projects. Participants come with projects or ideas which they wish to develop into an animated documentary. We do ‘matchmaking’ with fellow participants, tutors, consultants and eventually attach animation artist to the project, in order to create a trailer for pitching at our prestigious partner platforms. For our first run we’ve partnered with CPH:DOX and Doc. Leipzig, we’re releasing an open call for that soon. Teaching brings us a lot of inspiration for our own personal work as well; We’ve been teaching and working a lot with animated documentaries for the past ten years, I’d say.

For more information on Hollow Land and the work of Michelle and Uri Kranot you can visit their website at tindrumanimation.com/

To find out more about AniDox visit anidox.com. The deadline for applications is Feb 17th, 2014.