Harold Whitaker (5th June 1920 – 26th December 2013): Part 2

By the time Animal Farm was released Halas & Batchelor was gearing up for the start of commercial television in Great Britain in September 1955, and Harold and the Stroud studio were a big part of that planning. Significantly, all four of the other named animators on Animal Farm left the company shortly after that film was completed, and whilst many others came and went in the coming years, Harold was one of the very few constants in the department.

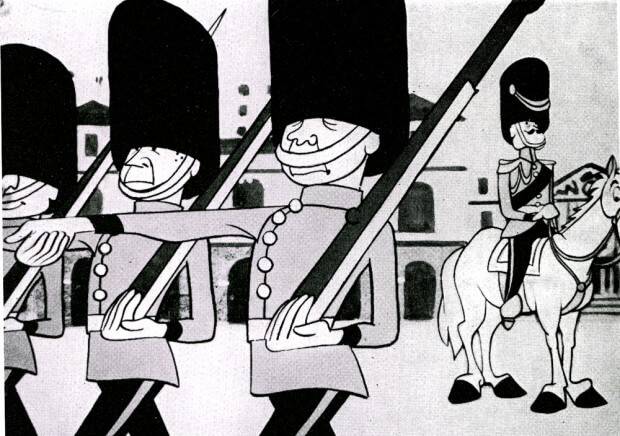

After the split with Anson Dyer, the Stroud team had worked out of a hastily converted domestic property, Tilbury House. Although pleasant, the space was inadequate, and in 1955 they moved to an old vicarage in Cainscross, a little further out of Stroud, where they had more room to breath. One of the first productions to come out of their new surroundings was a television commercial featuring cartoon guardsman singing the virtues of Murray Mints (“The too good to hurry mints”) which was animated by Harold. It was voted the favourite commercial in a Gallup poll on the first months of ITV and became a touchstone for such works.

For a Canada Dry commercial Harold experimented with drawing directly onto animation cels with wax pencils to recreate the style of children’s drawings, and found that he could produce effective animation at speed, eliminating the process of tracing pencil drawings from paper. This “cellgraph” technique was used by John Halas in an attempt to make animation for television financially viable. First came a series of six HaBa Tales in 1959, geared at adults as much as children, with simple moral stories such as that of the Cultured Ape (1959): a musical monkey who proved to be more civilised than the human society he was brought into. Harold animated four of the six films, revelling in a technique that demanded a swift, intuitive approach, because if the cels spent too long on the animator’s lightbox the wax from the pencils would melt and stick them together.

In 1960 thirty-three films featuring the character Foo-foo were produced for television using the same technique, in a series that eschewed dialogue in an attempt to find an international marketplace. Foo-foo was somewhat reminiscent of Chaplin’s tramp, forever falling in love with the voluptuous Mimi and falling foul of the nefarious attentions of the brutish Gogo. Watched in succession the episodes vary greatly, from Warner Brothers-style madcap energy, to a gentler, more considered pace. Harold animated at least five of the Foo-Foo films which bridge these different styles, suggesting that the tone was set more by the script and storyboard. And yet his animation is often instantly recognisable, even before the credits roll. Though able to turn his skills to whatever was required, when given free rein his preferred style of animation was a highly expressive, energetic, comic cartooning that is a joy to watch. His work is fluid and dynamic, stretching the boundaries of the character model sheet but remaining consistent and in character.

Alongside commercial television jobs, Harold was also working on sponsored industrial films, and the independent shorts that Halas & Batchelor produced with more artistic endeavour. Establishing a precise filmography for his work is difficult as so much commercial work is uncredited, and the details on the BFI National Archive’s database should be considered a work in progress, but his growing importance to the company is clear. In 1985 John Halas wrote a profile of Harold for Animator magazine in which he picked his own personal highlights from Harold’s work:

The extremely expressive “Keystone Cops” chase in “History of the Cinema”. The brilliant fluidity of the Matador and the comic shortsighted bull in “The Insolent Matador” (in the Habatales series). The charming characterization of Santa Clause in “Christmas Visitor”. The smooth and agile character of Foo Foo in the series of the same name. The musicians in the musical satire “Symphony Orchestra” for “Tales of Hoffnung”. The bouncy, dynamic wedding dance of Lord Ruddigore and the Bridesmaids in “Ruddigore”. The mischievous movement of Max and Moritz in the feature “Max and Moritz”. The regal gestures of Caesar in the feature film “Asterix” which was subcontracted to me by Idefix Studios. All these benefitted from Whitaker’s special skills in character animation. The tender gestures of the little girl and the abstract reactions of the skeleton in “Heavy Metal” were also examples of his art.

Interestingly, Harold himself was completely unaware of this article, and I had the great pleasure of sending a copy to him in 2010 (I also asked him what his own personal highlights were):

The J.H. article leaves me gobsmacked! I might add “Automania” and “Butterfly Ball” to his list of p.2. On the other hand “Max + Moritz” was flogging a dead horse. It might sound trite if I say I enjoyed them all, but animation is, or was, a fascinating pursuit. Tight deadlines were sometimes a problem, but we survived.

Harold was right to highlight Automania 2000 (1964), Halas & Batchelor’s best film and Britain’s first nomination for an Oscar in animation. Directed by John Halas from a script by Joy Batchelor, the film was realised through the creative efforts of Harold – the sole credited animator – and the fantastic design work of Tom Bailey, an H&B regular. The characters are made up of blocks of shape and colour rather than Harold’s more familiar line work, but still move in his distinctive sprightly, expressive fashion. The mountains of self-reproducing cars which take over the landscape were achieved through an intelligent combination of cel and paper cut-out work, demonstrating his excellence in thinking through the mechanics of economical but effective animation. He benefited from working closely with the camera units based at Stroud, and his relationship with the technicians behind them like Sid Griffiths (mentioned in part 1) and Len Kirley.

My own personal favourite piece of animation by Harold is further evidence of his logical but playful mind. In the 1969 film Topology Harold directed and animated a 9-minute exploration of this mathematical concept of shape and space, based on Stan Hayward’s storyboard. The shapes covered in the film become increasingly complex, graduating to the Klein bottle which is problematic enough to draw, let alone animate. Harold revels in a particular animation sequence in which a character repeatedly pulls a complex shape inside-out through a hole in itself without looping or repeating a single drawing. The scene does little to advance the educational narrative, but is clear evidence of an animator revelling in a complex test of his craftsmanship – one which he passes with flying colours.

For two years in the mid-70s The Old Vicarage became an animation school, with Harold inducted as the perfect candidate to give a group of art school graduates a crash course in animation. The first year saw 6 students, the second year 12, with graduates like Brian Larkin and Graham Ralph becoming an important part of Halas & Batchelor in the late 70s, before going on to found their own companies.

John Halas and Joy Batchelor sold part, and then all of their interest in the company that carried their name from 1968 onwards, but in 1975 they bought the company back and Harold was made a director of the company in recognition of his contribution. It also meant a move for the Stroud unit to “The Acre” a large C19th house, a very short walk from Harold’s home for his final years. For much of the sixties and the early seventies Halas & Batchelor had looked to the United States for much of its work, producing television series such as The Lone Ranger (1966-1969), The Tomfoolery Show (1970) and The Jackson 5ive (1971-1973). In its later years the company was more involved in European co-productions such as The Twelve Tasks of Asterix (1976) and adaptations of the works of Wilhelm Busch. The company did produce sequences for the Canadian sci-fi fantasy feature Heavy Metal (1981), with Harold directing the framing “Grimaldi” sequence and animating on “So Beautiful, So Dangerous”. His ability to work on all of the above and bridge every style from limited to full animation without fuss or distraction reveal what a model employee he must have been.

Most importantly 1981 also saw the release of a book based on Harold’s animation experience “Timing for Animation”, still in print today through a 2009 edition updated by Tom Sito to encompass digital animation. Co-authored with John Halas, this is really Harold’s book but he admitted that he probably would have kept tinkering away at it endlessly without result if it had not been for John’s encouragement and focus. It is an important legacy for Harold’s work and a mainstay of many an animator’s bookshelf.

The ownership of Halas & Batchelor again ran into choppy waters in the mid-80s, but Harold continues to provide work for John Halas’ other projects such as the Great Masters series looking at the work of Botticelli and Toulouse-Lautrec. In 1987 The Acre was sold off and demolished with a block of flats built in its place but Harold continued to work at an animation desk in the attic of his home. He was also employed by one of his old students, Brian Larkin as part of the company Animation People, as well as freelancing on When the Wind Blows (1986) and other films before finally retiring the mid-1990s.

Harold did have interests outside of animation, and his home had displays of pottery fragments and other archaeological finds that he had found in the surrounding area. He painted watercolours, and the lack of a new Christmas card produced by Harold for his friends and former colleagues last year was a sign to many that his health was failing. Often labelled as shy and retiring, he was perhaps better described as reserved. His work is a legacy of his sense of humour and keen observation of people, and the scenes of him larking about in the 1948 film Cartoonland or modelling poses for the farmyard battle scene in Animal Farm reveal his playful side. He compiled an informal history of animation in Stroud which he shared with interested animation historians who sought him out in later years and was proud of his own part in British animation history – a history that would be much poorer without him.

Author’s afterword: I visited Harold three times between 2010 and 2013 and always found him a charming, friendly and hospitable host, with extreme patience in answering my often imprecise questions. But a mixture of not wanting to outstay my welcome, and letting other things overtake me meant that I didn’t ask all the questions I would have liked, and those I did ask tended to focus more on the beginnings of his career. Therefore this second, concluding article on his life and contribution to the art form he loved is less precise than I would like. I hope to continue exploring and writing about his work in the coming years.