Harold Whitaker (5th June 1920 – 26th December 2013): Part 1

Walt Disney’s success was built not just on a mouse but also his “Nine Old Men”; a core group of animators who advanced their art form exponentially through a series of magical short and feature-length cartoons from the 1930s onwards. Britain has never really had a comparable industry for such films, certainly on the commercial front, but we have now lost our “One Old Man”, Harold Whitaker. If his name is unfamiliar to many, even within the animation field, it is partly because he was never a filmmaker himself. He wasn’t interested in directing, scripting, or character design, although he often had to turn his hand to many of those jobs. Harold was first and foremost an animator. His job was to bring life to drawings and bring drawings to life. In a career that spanned some fifty years, he animated some of the most memorable scenes of British animation history, including the downfall of Orwell’s drunken Farmer Jones in his country’s first feature-length cartoon Animal Farm (1954).

Harold Whitaker at Tilbury House, Stroud, c1952 home of Animation (Stroud) Ltd., a subsidiary of Halas and Batchelor

Harold Whitaker at Tilbury House, Stroud, c1952 home of Animation (Stroud) Ltd., a subsidiary of Halas and Batchelor

Harold was born in 1920 to a recently married pair of schoolteachers in Cottingham, East Yorkshire. His mother stopped teaching, and whilst his father worked as a maths teacher into the 1950s, his true passion was for music, playing a variety of instruments and conducting the school orchestra. Harold learnt the piano from the age of seven onwards, practising at least an hour a day diligently, but his passion for art also surfaced early. He remembered using the remains of school tear-off paper pads to make miniature flick books and he excelled in his art classes, graduating from Stretford Grammar School to Macclesfield School of Art.

His father encouraged him to fill in an application form for the local Midland Bank but through the efforts of his teachers he was offered a placement in London at one the country’s biggest commercial art studios, James Howarth and Brother in Soho Square. His duties were fairly menial, tearing out clippings of competitors work, buying materials, but occasionally he was asked to do lettering or touch-up work. At the same time he continued his studies part-time, taking illustration and life classes at an art school for printers at Bolt Court in Fleet Street. An equally key part of his continuing education were the seasonal selections of Disney shorts he would pay sixpence to see in London’s news theatre cinemas. When the programme of films such as Clock Cleaners and Pluto’s Quin-Puplets (both 1937) was finished he would often remain seated and watch them round again.

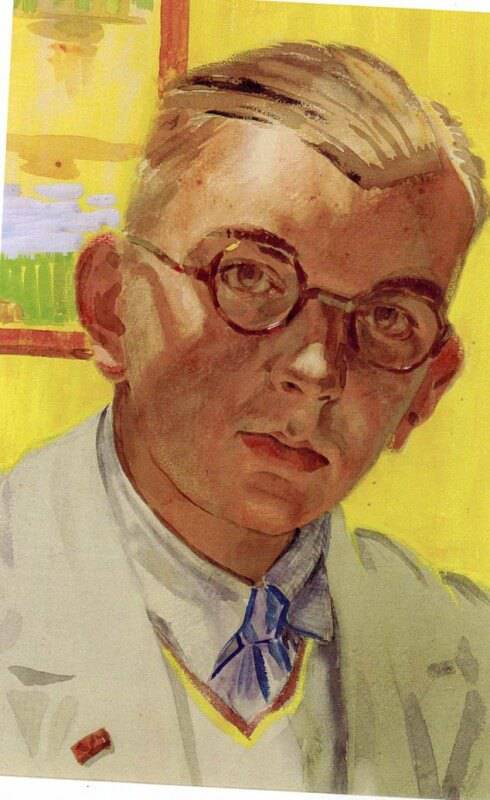

Harold Whitaker Self portrait (c1937)

Harold Whitaker Self portrait (c1937)

Although those who met Harold often describe him as a shy and rather retiring figure, he was not without confidence and ambition. He submitted some of his drawings to a competition ran by Punch and won a scholarship prize as a promising comic artist – he told me that the award ran for two years and the other winner was Ronald Searle, which is not bad company. This award proved important in two ways, as it got him a deferment from being called-up to the army, and it was a useful calling card for his newly acquired agent to bring in some freelance commercial illustration work.

Harold had experimented with animation whilst in Macclesfield and his agent showed his work to Bill Larkins and his assistant Alexander Mackendrick (later to come to fame as a director at the Ealing Studios) at the J Walter Thomson advertising agency. At that time JWT were producing a series of advertising cartoons for Rinso washing powder with Anson Dyer, Britain’s leading animation producer at that time. Dyer had been producing animation on and off since 1915 and was already in his mid-70s by the time Harold met him. He was not looking for animators at that time, particularly inexperienced ones, but he gave Harold a job painting backgrounds. At the same time the studio itself was being called up to the war effort and put to work making aircraft recognition films for the military. Producing such important work in a glass-roofed studio in central London proved incompatible with the nightly blitz and so in the autumn of 1940 the whole enterprise was moved to Stratford Abbey, a former girl’s school in Stroud, Gloucestershire. Only six weeks into the job, Harold went with them and found every opportunity he could to assist with the animation drawings. He remembered one particular sequence of an archer in a naturalistic pose that needed to be completed for a gunnery training film. None of his more experienced colleagues could get it right as their styles were too cartoony, but Harold took a stab at it and it worked. He borrowed Dyer’s book of Muybridge photographs and produced another successful sequence of a swan flying (he confessed that he never gave the book back and it remained on his shelves when I visited him).

Harold Whitaker posing for faces of Farmer Jones (c1953)

Harold Whitaker posing for faces of Farmer Jones (c1953)

Just as he was coming into his own, and being given the opportunity to develop his own instinctual flair for the form, his deferment ran out and he was called up in February 1941 – “a dreadful day, I could have just died when that happened. Leaving it all behind, just when it was beginning to take off, you know? But still… it turned out all right in the finish.”

After he was demobilised in December 1946 Harold returned to Stroud and found a job still open for him. Outside of a core few, the turnover at Dyer’s studio seems to have been high, possibly because most found the Stroud lifestyle a little too sedentary. Over the next few years Harold established himself as the lead (sometimes only) animator at the studio which at times struggled to keep work coming through the door. Anson Dyer was now in his eighties and had little or no creative input into the studio that bore his name. He benefitted greatly from the unpaid overtime that Harold would willingly put in on evenings and weekends as he learnt his trade. A short documentary profile of the studio called Cartoonland or Make Believe was made in 1948 and shows a rather energetic Harold at a story meeting, enthusiastically miming out ideas with colleagues, and happily at work at his animation desk. Barely featured in the film but a big part of the studio was Sid Griffiths, a mechanical wizard who had made his own cartoons for Pathé in the 1920s featuring a little dog called “Jerry the Troublesome Tyke”, but was now more involved in finding technical solutions to the problems caused by the company’s lack of financial means. Outside of work the two men shared an interest in astronomy and Sid built an intricate mount for Harold’s telescope.

Harold Whitaker at Anson Dyer’s studio c.1947, seated bottom right looking at the camera

Harold Whitaker at Anson Dyer’s studio c.1947, seated bottom right looking at the camera

Dyer was helping make ends meet by leasing parts of his studio to animation companies from overseas who needed to photograph their animation cels in the UK to take advantage of the only Technicolor processing plant in Western Europe. One of these companies involved a French producer, André Sarrut, who became very interested in Harold and began to give him work, involving trips to Paris to get direction, whilst still working for Dyer. At the same time he was producing a full colour cartoon page for the front of Mickey Mouse Weekly every week featuring comic strip versions of Disney features like The Wind in the Willows (1949), Cinderella (1950), and Alice in Wonderland – something that Harold kept up for three years and nine months without missing a deadline.

Sarrut was interested in taking over Dyer’s studio, looking ahead to the arrival of commercial television in Britain and the growing market for cartoon advertisements. At the same time, John Halas, now the leading animation producer in Britain, had also made it known to key members of Dyer’s team that he would be interested in taking over the studio to work on Animal Farm. Harold bashfully later speculated, probably correctly, that it was mainly him that the French company was interested in. Perhaps suspicious that they might be surplus to requirements for Sarrut, the staff resigned on mass to be reemployed as part of Halas & Batchelor Cartoon Films. Anson Dyer, who Harold remembered as a very charming, likeable man, but a figure of another age, was outraged but there was little he could do. Harold absented himself from the whole decision, returning when the dust settled, but was happy to go with John Halas, which almost certainly proved the right decision for him in the long term.

In what must have been a thrilling change of pace, Harold was now one of five lead animators on a feature film under the animation director John Reed, an American who had worked at Disney on films like Fantasia (1940). Reed had come across to Britain with David Hand, the supervising director on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), to build an animation studio to take on Disney as part of a financial folly by J. Arthur Rank. The other four lead animators had all been at the now folded Gaumont-British Animation and had benefited from three years of training there. Harold was something of an outsider, the only one based outside London in Stroud. Over the years, Harold built a kind of exhibition to his working life in his home and he treasured things like the “sweatbox notes” that John Reed produced in response to line tests of Harold’s animation drawings. Harold was handed the notoriously difficult human characters to animate in what attempted to be a more naturalistic, “non-Disney” style film. For those familiar with a seemingly shy and retiring Harold, photographs of him acting out key positions for a farmyard battle scene as a reference for his drawings are perhaps surprising. Constrained somewhat by the character design, particularly the unusual faces, his animation is one of the most successful parts of the film.

End of part 1…