Fantasia: 80 Years of High Tunes and Low Melodies of Disney’s Musical

Fantasia, the third feature length film from Walt Disney Studios, celebrates this year with its diamond anniversary and has remained one of the most experimental and unique pieces of animation produced by the iconic studio throughout the past eighty years. This orchestral-filled musical would also be one of the most ambitious films that Walt Disney himself would helm, collaborating with a famed composer, a team of technicians who would develop new sound technology and test his talented animators to their limits. So let’s dive into the history behind this classic title and the lengths that everyone involved put in to push the theatrical experience of the time and paved the way for future releases to come.

The film originally started as an idea for a short film to boost the popularity for Mickey Mouse after his fame fell from competing with other characters introduced from the late twenties to the thirties, including Popeye, Betty Boop and Disney’s very own Donald Duck. In 1936, Walt Disney started to work on the film, which was then going to be part of the Silly Symphony musical short films that his studio produced at the time.

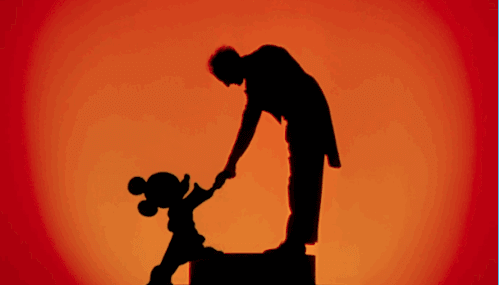

The following year, Disney encountered a famed composer named Leopold Stokowski at a restaurant. Disney discussed the concept of Silly Symphony to Stokowski and how he was going to use music from Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice as the basis of the film. After trying to pitch him on the idea, the composer expressed an interest on collaborating on a feature film instead. But as Walt Disney was still producing the short film, he didn’t want to change his project then to work on this collaboration.

When the budget of the short film exceeded over one hundred and twenty five thousand dollars and with little chance of it to earn back the money, he considered Stokowski’s idea to make the film a feature length production. Disney invited the composer to come on board on the film in February of 1938 and was the start of the experimental feature that became more than just a project to reignite Mickey Mouse’s popularity.

After Disney, his writers and Stokowski picked seven pieces of classical musical that would be included in the film, the collaboration of Stokowski conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra and Disney’s technical department paved the way for the future of surround sound technology. Disney instructed Bill Garity, the Head of the Technical Department at Walt Disney Studios, to experiment with the film’s soundtrack and be able to surround the audience to immerse them in the orchestral tunes and melodies that Stokowski and his orchestra would produce. Garity and his team of technicians created Fantasound, which used ninety nine speakers in a total of fourteen theatres, costing each establishment forty five thousand dollars. The team’s efforts did earn them a special honour from the Academy Awards in 1941 for this advancement in sound, while Stokowski also received one for his contribution in the film.

Mickey Mouse shaking hands with conductor Leopold Stokowski

But as much as the technical department and the orchestra put into the film, the animators involved were responsible for creating some of the most iconic scenes and sequences in the nearly one hundred years of Walt Disney Studios’ library.

With the focus on experimenting for this production, they hired German animator Oskar Fischinger after he produced his own abstract animated short films that were a popular trend in Europe at the time. But after nine months trying to collaborate with the other animators, he left the team as his work was too abstract for what Disney was hoping to achieve and thought it might not appeal to the American audience.

But unlike Fischinger, not everyone who came on board were originally trained as animators. Jules Engel was originally a painter who Disney hired to do choreography as well as colour keying, particularly on The Nutcracker Suite; the sequence set in a magical forest that played with colour and light. After Engel completed his contributions to the film, he was hired from the studio once more to work on Bambi, paving his career in the animation industry.

Bill Tytla, who previously worked on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Pinocchio, became one of the key animators on Fantasia. Arguably one of his greatest achievements on the film would continue to live on long after the film’s release as he was responsible for animating the Chernabog in the Night on Bald Mountain scene. This towering and menacing demonic figure would become one of the most recognisable and fearful of the villains in Disney’s vault, even appearing as recently as the Kingdom Hearts video games, attractions at the Disney World theme park, and the Mickey Mouse television series from 2013 to 2019.

Fantasia was finally released in November in 1940, but as the film also turned into an expensive project and ended up with a budget of over two million dollars (a lot at the time), it unfortunately didn’t earn back the costs. Its loss of money continued as the European market was cut off due to World War Two, which was forty percent of the studio’s income revenue back then.

All of these elements put the nail in the coffin for what Walt Disney hoped to do; make Fantasia a permanent release in theatres. By adding new songs and animated sequences, he hoped to edit the film once every so often for audiences to be enticed to return to see it again and again, gaining something new at each screening.

But much like Pinocchio, which also didn’t receive good results at the box office earlier that same year, it did earn back its money and gained popularity from audiences with its re-releases over the next few decades. Irwin Kostal, an Academy Award winning composer who worked on West Side Story and The Sound of Music, re-scored the film with the then state of the art digital sound in 1982 for it’s return to theatres. And with the numerous home video and DVD collections, it could be enjoyed again and again before the film’s move to the Disney+ streaming service.

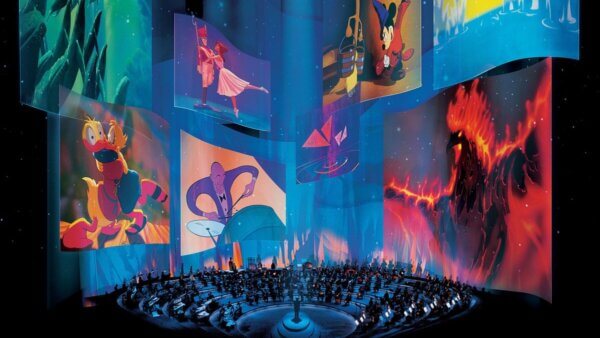

For the arrival of the millennium, Walt Disney Studios created a sequel titled Fantasia 2000 and while it may not be as talked about as much as its predecessor, it did win several film awards and was the first animated feature length film to be screened on Imax, trying to push the boundaries of sound and sight in theatres.

Whether you have seen the film or never dived into this unique piece of cinematic history, I hope that you celebrate it’s eightieth anniversary and watch Fantasia. It truly was, and still remains, one of the most uniquely experimental films that Walt Disney Studios, or any other animation studio, have released over the past century.