Interview with artist and ‘Howl’ Animation Designer Eric Drooker

When we reviewed Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman’s Alan Ginsberg biopic Howl last month we were, as one might suspect, particularly drawn to the film’s enchanting animated sequences that brought a new and exciting life to the iconic, titular poem. Today on Skwigly we meet Eric Drooker, the acclaimed artist, illustrator and graphic novelist behind these stunning visuals.

What sort of artistic background did you have when you first started making a name for yourself?

Although I’d won a scholarship to a prestigious art school in Manhattan (where I studied sculpture), I’m basically self-taught, because no one can actually teach you Art. A good school can teach you technique, and a very good teacher can inspire you. But true Art comes from within. So, It wasn’t until after I graduated school that my real education began.

Before you eventually met, how familiar were you with Ginsberg growing up and did you feel any sense of identification with his work back then?

I was only slightly familiar with his work. At the age of twelve, I’d heard a record of him reading his poem Kaddish. Though most of it went over my head, I was intrigued by the rhythm and cadence of his voice.

Are you a fan of poetry in general?

Most poetry (like most art in general) leaves me cold. It’s mostly cookie-cutter technique, boring, and uninspired. The poet (or artist) hides behind seductive forms, and rarely communicates who they actually are.

Eric Drooker’s sequences for the movie were adapted into a graphic novel, following on from his original works Flood! A Novel in Pictures and Blood Song

How were you originally approached by the filmmakers to produce the animation for Howl?

Initially, the filmmakers wanted to use my images for their upcoming documentary about “Howl.” But when I showed them my graphic novels, and they realized how much sequential art I’d created, they hired me to animate the compete poem. Next thing I knew, they’d hired Hollywood actors to play Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and Neil Cassady. So, the film morphed from being a documentary about the famous poem, Howl, to being a drama of the poem itself; and the subsequent obscenity trial, which the poem set in motion.

For the most part you’ve created visuals using razorblade-on-scratchboard, what is it about this process that appeals to you most?

Drawing with a razor blade feels infinitely more visceral than gliding over the surface with a pen or brush. Like woodcut, it’s a subtractive process; the ink is already there and I’m scratching it off with a knife. The hand-carved aesthetic lends itself well to extreme emotional states, passionate visions, and social criticism.

Having produced work traditionally for so long, did you have any reservations about the digital animation process?

I’m always curious to try new ways of expressing myself in various media; be it traditional oil on canvas, or pixels on an electronic screen.

Had you ever been interested/involved in animation beforehand?

Bugs Bunny has been one of my major role models since early childhood. (He never starts shit, have you noticed? He’s always minding his own business when some white guy with a gun starts fucking with him. After that, he plays by his own rules, with maximum retaliation.) But aside from a few flip-books I made as a kid, I’d never animated anything. And I never actively pursued a career in animation (it’s far too tedious). But when the directors of Howl hired me to animate Ginsberg’s poem (told me I’d have a team of animators who would follow my storyboard and bring my art to life), I couldn’t resist.

What was the scale of your involvement as the animation designer, and what level of control did you have over the end result?

I designed all the characters, created the key frames, and original storyboard. A veteran animator from San Francisco, John Hays, developed the storyboard further, and directed the animation team at The Monk Studio in Bangkok.

In making this film, were there any specific artistic influences drawn upon for the first time, possibly within the world of animation itself?

I didn’t draw much from the world of animation. But my artistic influences on this project included the work of William Blake, the German Expressionists, the American Magic Realists, and Film Noir.

Music and performance have appeared as themes in some of your work, do you feel a connection with the world of visual storytelling and music composition?

Since visual art is silent, I try to infuse my images with as much rhythm as possible. It’s been said that all art forms aspire to that of music. Animation certainly has a close affinity with music. Being a temporal medium, like dance, it must be carefully choreographed.

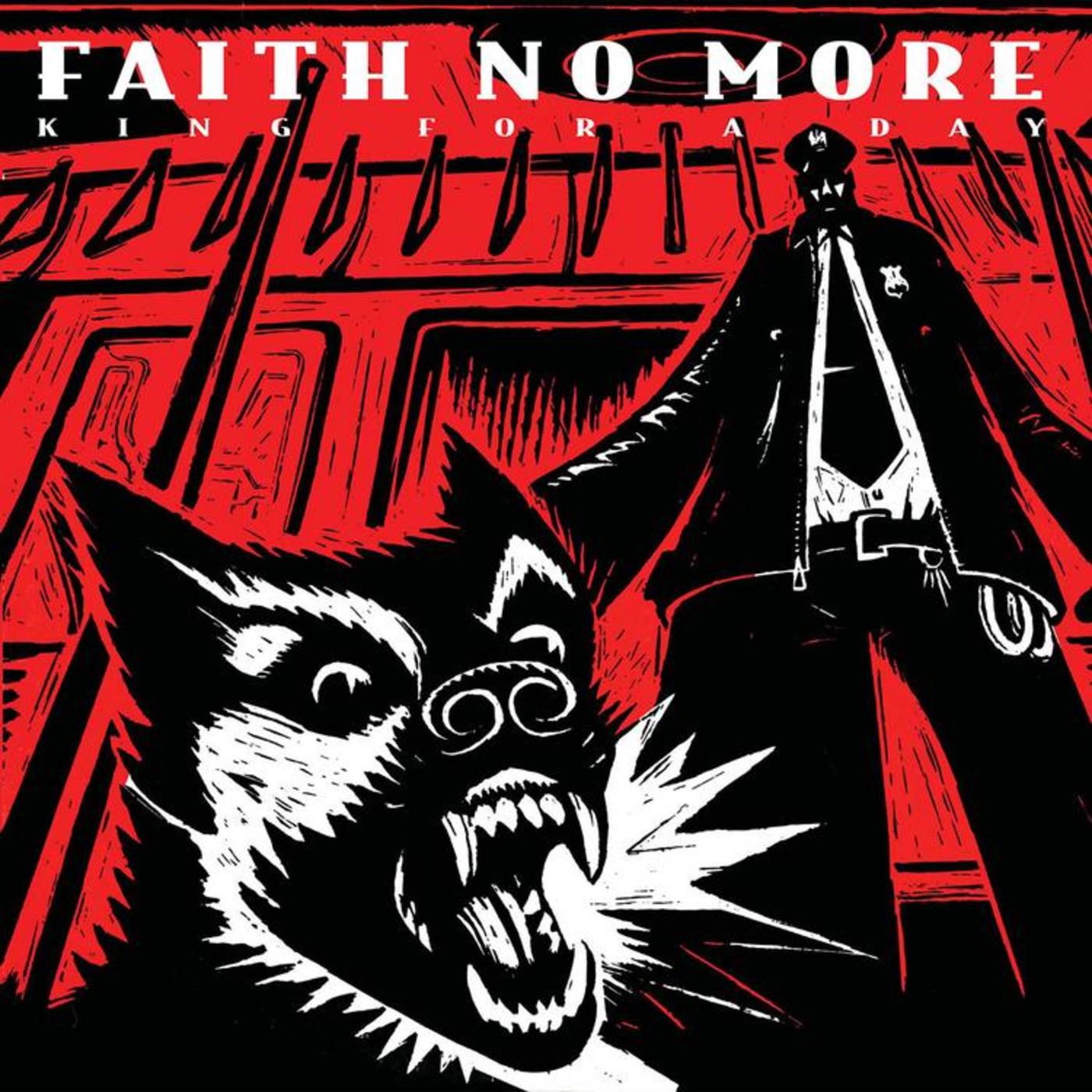

Bands such as Faith No More and Rage Against The Machine have drawn on Drooker’s distinct work for their album covers

Following on from that, do you have any opinion on the musical associations with your work (whether they are a successful fit and/or juxtaposition), e.g. bands using your imagery for album covers, and Carter Burwell’s score for Howl that accompanies much of the animation?

Countless bands have approached me about creating album covers. Punk, Hip Hop, and Jazz bands often feel a mystic connection to my work, which is cool. Though I’m often listening to folk music while making art.

How did your initial collaboration with Ginsberg’s Illuminated Poems come about?

I knew Allen Ginsberg from the streets of lower Manhattan, where I’d created a series of protest posters on a range of urgent local issues. The poet had seen my posters around the neighborhood, and had been collecting them. One day he suggested we collaborate on a poster together. Ultimately, we published a volume of dozens of his poems (and songs), which I illustrated with paintings and drawings. This book, Illuminated Poems, became an underground classic, and eventually caught the attention of the directors of Howl.

Did your work on that book lay the groundwork for creating the visuals with Howl or did you start with a completely blank canvass?

Many images in the book inspired animated scenes in the film, but the poem Howl is so long that I needed to spend a couple of years creating all-new imagery for the film’s numerous animated sequences.

As with your graphic novel work, the Howl animation features a lone character on a journey of sorts. Does this character purely represent Ginsberg, or are there other facets to it (e.g., fictional or autobiographical)?

The “lone character” seen throughout the film is a composite of the many desperate, creative souls I’d known over the years. He’s stark, raving mad . . . but it’s divine madness.

One of the more striking parts of the film is the “Moloch” sequence, and it’s been brought up that in writing it Ginsberg was influenced by Lynd Ward, who subsequently created his own visual interpretation of the passage. Was that a contributing factor to your own visualization for the film?

No, but I was enormously influenced by Lynd Ward’s wordless novels of the 1930s, which inspired my first two graphic novels, Flood! A Novel in Pictures, and Blood Song: A Silent Ballad.

A visual motif prominent in your novels that appears in Howl, are moments where the characters become translucent with their skeletons illuminated. Does this concept have any specific meaning or conveyance, and does the idea come from anywhere in particular?

The X-Ray motif, which I use frequently, is my way of depicting moments of emotional vulnerability, impending mortality, and a general sense of impermanence.

Visit the artist’s site at drooker.com

Howl (Dir. Rob Epstein/Jeffrey Friedman) is available to buy on DVD and Blu-Ray from Soda Pictures in the UK and Oscilloscope Laboratories in the US.

Howl: A Graphic Novel by Allen Ginsberg and Eric Drooker is available through Penguin Classics