Interview with Elliot Dear, director of ‘Love Death + Robots: All Through the House’

Elliot Dear is an innovative and creatively potent director currently represented by BLINKINK. He has carved a name for himself owing largely to his innate ability to combine the digital and analogue realms of animation production into a fresh new direction for his clients. a long-lasting inquisitive mind, that originated in his childhood, has promoted Dear to one of the most exciting and interesting commercial animation directors working in the UK today. From his hugely successful ad for John Lewis at Christmas in 2013 The Bear & The Hare that received millions of views not only on tv but online, to the 2017 BBC Christmas ident The Supporting Act. Both of which combined classic animation process with cutting edge technology and production methods to lend a nostalgic charm to the creatively and commercially sort after annual campaigns.

Along with his blend of new and old technology, the rather unusual claim to Christmassy subject matter made him the ideal fit for the first stop-motion Christmas episode for Netflix’s animated sci-fi anthology series Love Death + Robots, the brainchild of American director Tim Miller. We took this opportunity to talk to Dear, to discuss his humble origins, to work on a range of project scales, his thoughts on bringing different modes of production together and what value this has brought to both him as a director and to the audience at home.

(Image courtesy of BlinkInk)

Could you tell me a little bit about how you started in animation?

I’ve been making films since I was about 12, through making models, painting and being in the family shed using tools. My parents also saved up for a PC when I was 15. It was quite low spec, but it could run Corel Draw and a very early version of flash, which is now essentially animate in the Adobe Suite. I did a lot of stuff in that – bearing in mind there was no YouTube, there were no online tutorials. It was just kind of pressing buttons until it does the thing you want it to do which takes you fifty times as long because you don’t know the shortcut keys. It was just really fun. I actually wanted to go into special effects and animatronics. I wanted to be a model maker, that was my plan, but I couldn’t find a course that would do it. So, I went for illustration, it’s such a good broad base for any visual pursuit, in terms of colour, tone, composition, storytelling and life drawing, not that I was any good at that. In fact, I dismally failed my life drawing module but it’s fine, I always just own up and say I can’t draw people very well.

So, I did illustration but was always drawn to moving images. I ended up teaching myself After Effects. Again, we’re still pre-YouTube tutorials. Which was a very long-winded way of doing things, I didn’t even discover that ease function for a long time. So, I was doing it frame by frame, like you would in stop motion, it was really impractical, but I learned loads. When I left university, I got a job as a junior compositor at Arthur Cox which was great. It was the fastest learning I’ve ever, I learned from some really good senior compositors. University is great as you have luxurious amounts of time but there’s nothing like getting in the studio and working for someone else to teach you really, really quick. I was doing commercial work as an After Effects composer and then by night or over weekends I was directing music videos, but for like a hundred quid, it was essentially an excuse to try out new processes or tools. Any ideas I had, I want to put them into something, it was more about the experience. I started to get my work seen as a director, I was showing people my reels or getting up on the internet. YouTube was a thing by this point, I’m pleased to say and it kind of went from there. I ended up in London, a friend said there was a job going at an ad agency, then someone else saw my reel, then Blink spotted it and eventually signed me as a director where I am today.

I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. I never really thought I’d be an animation director. I was lucky enough to get onto the set of Fantastic Mr Fox when I was 24 as an intern for a few weeks. It was amazing, they were very welcoming, and I got to meet lots of people there. By the end of it, I just wanted to do all of it. I wanted to be in control of all of it. I thought it was fantastic. I still feel very grateful for the experience and all the people that I got to work with. I just wanted to oversee all of it because I’m a bit of a control freak. I like that. I’m an animation director, I can control everything. It’s not even like being a live-action director where there’s the possibility for happy accidents. There’s none of those in animation. It’s all in my control,

That’s great. So, you’ve forged quite a reputation for your use of innovative techniques with different kinds of production and performance to tell, phenomenal stories, but can you tell me what draws you to this mixed media approach to your work? And what do you feel it brings to the audience both emotionally and visually?

It’s an interesting conversation to have. I’ll be wandering around the house asking myself the same question because I also think why? Is it selfish? Is it just because I want to do it? It’s a few things, really, I was looking at some comments on Instagram that somebody left on one of the love death and robots clips and it’s the same question that I get a lot of the time, which is, why bother doing it in stop motion when you can achieve the same quality in CG? Which was one of maybe 500 comments most of which are saying ‘wow! it was stop motion?’. I don’t know what value that has exactly, but it seems to strike a chord with people, it’s tangible. I like objects with stories, that people have had their hands on. I don’t want to say there’s imperfection, because some of the artists that we work with are making their work look perfect, but it’s got a life beyond the screen. There are these artefacts of the film, with imperfection and human error, which is a great thing. I find it easier to connect, I like practical effects, I like knowing that there were people behind the scenes with their hands-on stuff.

Even in the beginning, I would animate on the computer but still make things in the shed. There is of course software for digital painting with digital brushes that look fantastic, and you could say to an oil painter, why would you bother? But they like the feel of the medium, they understand it, how it moves and how it works. I’ve done CG jobs, I’ve done full 2D jobs and I’m always impressed with the artists involved. I’m always fascinated with how it works. But I love being in a studio. My dad’s a carpenter, very wise, he’s just retired. So, I’m used to being in a shed with things being made all the time, I would go to work with him when I was a teenager. It’s an environment I like, I like being on a film set, which is kind of like a building site. Not quite as wild but there are wires, there’s scaffolding, there are people overhead, pulling up, changing things. I really like the energy of that environment. I like working with carpenters, painters, people that work with their hands and watching them make things it’s a real treat for me.

That’s not to say that people that work in CG aren’t – it’s an incredible craft, and it’s the same deal. It’s that level of detail going into it. I like being in that space. I like that being the way I spend my day. And it’s a fascinating place to be and I think that comes through in the work. There’s definitely a place for stop motion. There are definitely projects where it’s not suitable, a lot of the time I get jobs to come in, might be an advert or music video and people say we want to do stop-motion, but I think it should be done on the computer honestly. You don’t need it to be in stop motion. It’s not really an appropriate way of telling this story. I think it’s got to be used for the right reasons. I don’t like the idea of old ways dying out. I think keeping the tradition alive is good – just because there are new ways of doing things, doesn’t mean that you need to shut out the old ones.

Are there any other kind of considerations you have when you’re looking at a potentially new way of working when pitching?

You’ve already identified that I’m not a purist some people believe there shouldn’t be a lot of technologies. I remember when I worked on Fantastic Mr Fox, that was one of the things I found really interesting. An animator called Dan Gill, who actually ended up being one of our lead animators on ‘All through the House’, he’s fantastic. On Fantastic Mr Fox, it was his job to come up with the practical in-camera special effects, such as when the characters were being electrocuted when they go over a fence, these are things you could do in aftereffects or CG really easily. But Wes Anderson wanted solutions that happened in camera. I guess he wanted that kind of 1970s stop motion feel to it. Hence, smoking clouds and explosions made of fluff which looks great, it looks tangible. It looks like stop motion. What’s interesting, is that the reason they were done like that in the first place, would have been because that’s the only way they could do it. If you had given them a computer they probably would have done it that way instead. A lot of people working in practical effects would have loved the option to make something that looked more realistic. So, when people use practical in-camera effects now it’s because they like the aesthetic. It harks back to a time gone by and there’s some romance in that, a sense of nostalgia because it looks charming. It’s lovely, it’s not flashy, it’s quite a humble way to do things. I think that’s the reason for using stop motion a lot of the time.

(Image courtesy of BlinkInk)

I’m not a purist, there are elements of stop-motion that I really appreciate, like the tangibility, the being on set working with animators who work with their hands. I think there’s a lot that comes through in the final footage, that whether you know about filmmaking or animation or not, you appreciate as a viewer, there’s just a quantity to the footage, which is hard to emulate. At the same time, people can and should do whatever they like. But if there’s a bit of fire or mist from breath because it’s cold, I’m more than happy to do that in CG. For example, the monster in ‘All Through the House’ has drool that comes out when he opens his mouth, to that in-camera would have tripled the length of the shoot. The CG team in Norway did an incredible job of making it look real and they put it on twos wherever is necessary. I’m all for that. I think that’s fantastic and enchanting. But at the very base of the footage, it is stop motion. So, it’s still got that heart, stop-motion is the foundation of the footage but then it’s augmented with other things, which makes it more believable, which makes for a better viewing experience. Again, it’s not the best way of doing it, it’s our way of doing it. I think it’s just trying to naturally find that balance. Where do I stop and just make it on the computer? When does the stop motion part become pointless? Where did I start wasting everyone’s time? So, it’s just making sure that I’m, keep asking myself that question.

I think when you’re building a world, it’s about creating those rules and which roles you’re going to apply to different things, is everything going to be stop motion? Or are you going to have elemental things that wouldn’t be tangible and real life, are those going to be digital? it’s all rules and preferences as a Director. It’s your choice to decipher that line.

I think there are absolutely rules to the way that I do things, but they do change. It depends on what it is, for ‘All through the House’ it’s set in a house. We didn’t need any digital set extension; we didn’t need to be doing big digital matt painting for the sky or CG city on the horizon. So, it’s just picking the right tools for the job.

When you are bringing all of these various elements into production, does that affect your control as a director? when you don’t necessarily have that specific skill set, how does that alter your control over the production?

I just make sure that I learn about it as quickly as possible. Again, going back to what I said about learning on the job being the fastest way to possibly learn. I’ll ask a lot of questions, do a lot of research. I would never walk into a CG studio and say I understand all of this. If I don’t understand I will ask and try to have some humility and ask them to explain bits to me or ask how does this work? And more often than not, people are perfectly happy to give me a bit of a brief on what’s going on. But working in commercials jobs can be quite short. Again, like when I was starting out making music videos, I could try out a bit of kit or try a new technique. When we do a commercial, we may go, alright, how about stop motion with CG faces because that will be really good, and work it out on that short job. Then that’s another string to your bow, you get control back when you keep learning. It does mean that you have to work with a team that is willing to bear with you a little bit.

This constant need for re-skilling is a big part of filmmaking especially in animation because there’s just so many possible pipelines and ways to do things?

Absolutely, it’s a tricky one with the CG work, I know if I said, I’m not going to learn anything about CG, just make it work, it would still get done, but probably not as well, because I wouldn’t have the vocabulary to have those discussions and the person doing the CG would have a terrible time. It would be such a chore, to have to work with somebody who didn’t know what they were talking about, I think. You see that loads, people refusing to learn. When people ask for animation in advertising, they’ll say, we want this, but they don’t want to know how animation works and it would really help if you did, because then when they ask questions, they would know the answer is we need more time or, even that it can’t be done. I think it’s important for that reason, you just don’t want people you’re working with to be having a terrible time. So, it’s worth trying to learn as much as possible so that you have that vocabulary.

I always think it comes down to respect really.

Yeah, it absolutely does. Also, the skill in this industry is unbelievably high, you can’t help have respect. But you know, having the title Director, for some people I think it makes them feel like they’re at the top of the pile and whilst there is a lot of responsibility, you have to acknowledge that you can’t do it on your own. I tried for years, that’s what I did all through my 20s, made stuff on my own, and you just need other people if you want stuff to be that much better, that much bigger and have to recognise that. Which keeps you levelheaded and on the same level as the entire team.

For Love, Death and Robots, which was really beautiful. It was the first use of practical puppets in that series. How were you first approach to work on the project? And what was the experience like?

The job came in for blink industries, they had seen the ‘The Supporting Act’ at an expo or showcase in LA and traced it back to us. It was the first project we used CG face tracked on to stop-motion puppets successfully, which at the time I was a bit of Hail Mary, but it worked, which showed us the potential for that technique. So, we pitched on the jobs in the same way we do for commercials. We spoke to Tim Miller and Jennifer Yu Nelson, about the process. Tim runs a CG studio, amongst other things, and fully embraces technology. They are at the top of their game with what that they do. He wanted to make sure that this wasn’t just going to be a novelty film in the anthology, it needed to still be cutting edge and fit in with the rest of the films. He didn’t want in-camera practical effects, he wanted it to feel slick, but for it to still look like a stop motion film. We were quite a good choice because we could get that hybrid look.

We put together a really good pitch document, which I was really pleased with. It was super intense but a really good learning experience. I’ve been making commercials for over 10 years now, so had become accustomed to having a certain level of authority in my work. But suddenly I was bottom of the pile again, I’m working with Tim Miller and Jennifer Yu Nelson, incredibly successful feature directors who I really respected. We did an initial storyboard and added loads of ideas to the script because, in advertising, there’s usually an unspoken invitation to make changes, which is almost always necessary. I chucked things in, took out lines of dialogue, and gave them this animatic. They were alarmed about the quality of the animatic, it was one of the best animatics that I’d had to work from, but these are people that work in Hollywood. They are used to banks of people at desks doing storyboards, on staff in their studio. Whilst our borders work for us for a week then there often gone on to another job. I don’t normally require that, I’ve gotten things done with a lot less, even no storyboards, they understandably wanted changes. We were also not allowed to change the script, Tim spends a long time working on those scripts and the stories are very close to him. It was a very different industry almost a different world. I think half the job was actually showing them that they could trust us. I was learning so much from them because there so experienced and talented.

What was the biggest challenge in the project?

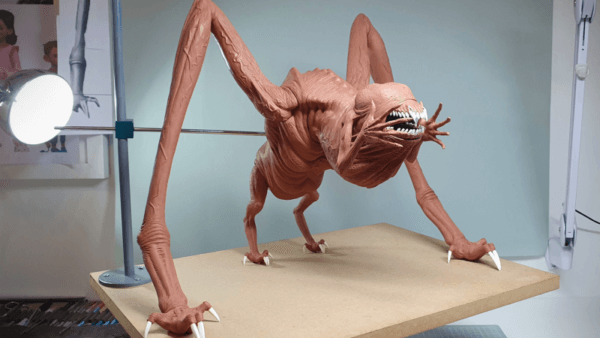

The creature design was one of them. I worked more directly with Jennifer, Tim being as busy as he was, but there was a point where we had a creature design that we’ve been working on for weeks and weeks. It was signed off and sculpt double who had started to build it. Then I got an email saying Tim’s not happy with the monster, he doesn’t feel like it’s frightening enough and doesn’t look enough like a predator. So not only did we have to stop, but also find the money for the re-design, what actually happened was, I ended up doing the creature design. I put a questionnaire together for Tim with things like; do you like the claws on this? Do you like the teeth of this? with loads of reference images and he also sent a lot of great references. Eventually, we got to what he wanted which was loads of fun. I think the biggest challenge was just how big and professional they are in regarding the standards they were looking for – Hollywood quality animation and whilst I’m confident in both my and the people I work with skills, it is still daunting. We also had about half the budget we would normally have for a commercial for the length. We really had to be resourceful, there were points on set where we tried to get two story beats into one shot rather than two, to consolidate shots and lighting setups -that’s how tight it was.

When you work in stop motion, it can take days to set up a shot. When you’ve only hired out the studio for four weeks, there’s no dilly-dallying. These are the things people don’t realize when they watch the film. We had a performer who did all the acting for both the kids so that the animators had references to work from, but when we got on set, we only had like four hours to get the shot, so we would try and get the shot in 75 frames instead of 150 frames. So, I’d be working with the animator shooting stuff on a phone, trying to get that performance down, I’d be running around in the car park or hiding behind the sofa, trying to see if I could get that performance down into a shorter time. Which was possible a lot of the time, it was just tough to shoot it 50 times stick it in the edit, time remap it and go alright, there’s your reference. We were putting out loads of fires on set, not literally, of course, there was a lot of problem-solving but if you didn’t directly ask me, I would have forgotten how tough it was because it was so much fun. And because of what we got out of it. I feel it came out really, really well.

That’s one of the nice things about stop-motion, it really is a medium that calls for great problem-solving and if you have that kind of mind where you really enjoy problem-solving, then stop motion is the medium for you.

It’s quite intoxicating, actually solving those problems. I think being on set having a deadline, having all those great minds together. It’s just really exhilarating. Working with the people that you get to work with and that kind of collaborative problem solving, when you nail it or solve it, and then it gets signed off, you think that was probably better than if it had gone smoothly. Having challenges, just get your brain working if nothing else it’s good exercise, good brain exercise.

How do you feel your film sits within the rest of the series?

I mean, it’s much shorter. Which makes it different. I’m never going to be able to really answer that objectively or watch it objectively, that partly why I like to read comment sections, and partly because it’s nice to see that people are enjoying it, it’s quite entertaining. Most of the comments from people are that the whole series is too short, there are eight episodes. I think people have forgotten that they were being made during the pandemic, there’s so much work involved and you can’t make it in the same room as anyone but you know I think it does sit well with the others in the series-people do assume it is CG. I think as a Christmas film within the anthology, there’s a legacy between stop-motion and Christmas specials. Which we kind of hinted at in the film, which perhaps makes the use of stop motion make more sense. So even if people did find it jarring for that reason, it would be for a good reason. The fact that it got signed off and Tim and Jennifer were really pleased with it tell me that it did the trick.

As you mentioned earlier, the puppet faces are CG composited. What does the use of digitalized mouths on the real puppets offer you as a director?

Nuance, I think anyone who works in stop motion will know that puppets have their limits and I think lots of people embrace that. Depending on the design choices that you make, it doesn’t always matter. Especially if movements are allowed to be bigger, more stylized, and cartoony. Aesthetically, what I like is just shy of realistic. Stop motion puppets that have dots for eyes and mouth shapes that snap into place are obviously going to work perfectly in camera but I’m yet to see a puppet that has a mechanism that can do the things that I wanted them to do. 3D printing is interesting and everyone’s entitled to make things the way they want, like doing it in-camera if they want. To me, it seems like quite a complicated process. You work in CG, you print out a lot of faces, then you put them on the puppets, but then the jobs not finished because then you need to paint out the seams before it ends up back on the computer again. We couldn’t have afforded to do that if we wanted to. Also, there is still an element of stylization in the movement because those face shapes are going to snap a little bit, from one to another, there are going to be texture variations. LAIKA obviously do incredible work with their cleanup, it’s very finely tuned. But what I want is even smaller, really little facial expressions and things because that’s the types of performances that I like and it’s not until you get on the computer and you start moving things around in CG and the difference between the eyelid being moved is a fraction but changes the whole expression.

You can go from uncanny to charming, or the movement of eyebrows can be worried or not, through these tiny, tiny little movements. I would say it’s about control, I love the control. We had good reference footage. I was doing some facial expressions videos for the guys. The animators onset and stop motion animators had what they needed in terms of body language and performance, and they had the footage with expressions to let them know the intention of the shot that they were going to make. Obviously, they didn’t have any control over the face, except the eyes, which they could get a pin in them and move them which helped them with performance.

Was that the same for The Supporting Act film?

No, they were completely locked masks. The faces were blank, and the eyes couldn’t go anywhere. So that one difference with ‘All Through the House’ the animators had, eyeline’s to work with, it just meant that afterwards, I could absolutely fine-tune those facial expressions. It really was fine, I would get shot back from Storyline in Oslo and I would take a screengrab of it run it through Photoshop and use liquify. Then I could move things around – move eyelids up, nudge, just tiny little, minuscule things with the eyes and eyebrows mostly and then they would fix it in CG. Again, people don’t see this part, it really is such a layered process in order to get that believability and not fall into the uncanny. I look at the work of Disney and Pixar and all you’ve got to do is watch the facial animation in their movies, and you think that’s what we need, for that emotional connection. That nuance and detail.

Were you aware of any kind of like feelings in terms of the division of labour between the animators working on set with the real puppets and the animators behind the computer in regard to performance and how that changed their ability to perform?

If there was, they never expressed it. We had the same guys, Stan, and Andy, on the BBC job. They understood how it worked. It does make their job a lot quicker when they don’t have to do the faces. I don’t think they were concerned over any kind of ownership over the performance, they seemed excited to see the CG go into it. It made it a lot quicker, they were able to focus on the body language, there’s still loads of detail and nuance in those performances. So, they had more time to dedicate to that and because we also had specific live-action references too. They had a lot of work to do as they weren’t super-stylized movements that you could perhaps use shortcuts with, with the live-action video references it really needed to be right. I think the CG team in Norway also enjoyed it. I think again, on the one side you don’t have full control over a character. But on the other side, you only have to concentrate on one aspect of the character and maybe that’s nice, I don’t know. But they seem to enjoy themselves. They were very pleased with the results. It made the whole process better for me, it did just mean that I had to keep everything in my head, if I had dropped the ball and the communication wasn’t there the whole thing wouldn’t fit together, between the two processes. It could have gone really wrong, I think.

Love Death + Robots: All Through the House (dir. Elliot Dear, image courtesy of BlinkInk)

You have such a diverse range of talents. You’ve worked with live-action, CG, 2D and Stop-motion, and often combine them all to such a high quality. Is there anything you’re particularly excited about trying out next?

No, not anymore. I think there was a point where I wanted to try out everything. So I’d try it out for a music video or on this commercial. I feel I’ve gotten to the bottom of a lot of the things that I was wondering about, like the CG faces. I imagined there will be other things that come up eventually, but I’m not going to say I’ve done everything in animation now. I’ve just worked on such a variety of things which has allowed me to build my knowledge and skills in various areas. What I’m able to do now is to respond well, to a brief, I won’t say every brief.

Now we use the right tools for the job, it might be to get that stop motion feel, that tangibility, that nostalgia – that you get from a Rankin Bass Christmas special. But we still want the faces to be really detailed so we will combine these things and put them together. I think I’m better at responding to briefs now and able to do the people want, rather than kind of shoehorning in a process because I wanted to try it out. I feel like as I get older and more experienced, there’s less of that. Now it’s more about what do you need? What does this project need? What does this story require? In order for it to be told in the best possible way. So, I think that’s how I work now.

You can find out more about Eliots Dear’s other work on his directorial page at BLINKINK here. Or follow him on Twitter or Instagram. You can also watch the interview as part of our animation one-to-ones here or listen below: