‘Day of the Tentacle Remastered’ – Review

If I were to do the fair thing and disregard the Super Mario franchise, my two fondest memories of playing video games as an adorable whippersnapper also happened to be, in their own way, two of my biggest visual, creative and stylistic influences. This was doubtless because they themselves were inspired by the classic, manic era of animation that hit its stride in the forties and fifties. Following the much-lamented glut of merchandise-driven eighties IPs, The Simpsons had reminded the world that cartoons could be smart and dialogue-driven, while Ren & Stimpy had reminded the world that they could be insane and unrestrained. This renewed interest in animation during the early nineties bled into some video games that had, by good fortune, just about reached a level of technological sophistication that accommodated it. One such game was Doug TenNapel‘s Earthworm Jim, my fondness for which has been no secret. A preceding title that ever-so-slightly trumps it, however, was a revelation to a lot of console-oriented videogamers like myself at the time.

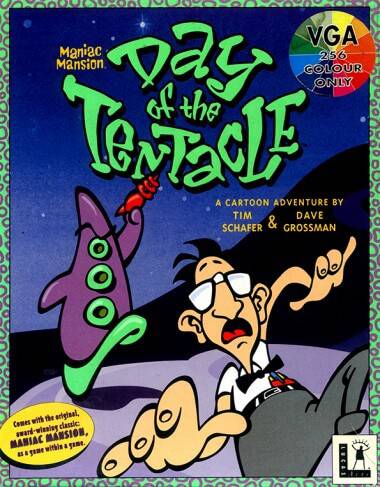

Day of the Tentacle (a 1993 sequel to the 1987 game Maniac Mansion which had already become an old chestnut) was one of the earliest examples of a point-and-click adventure that was, essentially, an interactive cartoon. Along with similarly engaging outings as Steve Purcell’s Sam and Max series, Ron Gilbert’s Monkey Island series and Tim Schafer’s Full Throttle, Tentacle (a product of Schafer and fellow Monkey Island vet Dave Grossman) handed young gamers an almost directorial set of reins as far as the order and manner in which events might play out. To a nine-year-old this was a truly wondrous concept, and in my quasi-adulthood it has dated surprisingly well, for a number of reasons:

- It isn’t easy, but that being said I have the entire walkthrough eerily memorised to this day. I say ‘eerily’ because I can’t even remember what I ate for breakfast yesterday.

- It’s still pretty funny, for not necessarily the same reasons, but lines like ‘Ted is red, see red Ted’ still keep me a-chucklin’ like the emotional-stunted fool that I am. At the time to just have the characters speak at all was brilliant enough.

- The excellent sprite animation, obviously the more pertinent aspect in the context of this review. Clearly a love letter to Tex Avery, Chuck Jones and that whole Termite Terrace rat pack, it featured superb character acting and some nice dashes of craziness. The background paintings were especially gorgeous to look at, even through a haze of a resolution so low you could probably count the pixels on sight.

The premise was fittingly nonsensical – referring to exposition set up in Maniac Mansion (which I never got through) the player switches between three college students who explore the same building in the past, present and future respectively. The gameplay involves using one, two or all three characters to solve a series of bizarre puzzles – an example of the abstract thinking required being: the guy in the past needs vinegar to help power a battery, so he has wine transported from the present which he then seals in a time capsule. The girl in the future then has to locate the capsule, open it and send the bottle of what-has-now-become vinegar back to the past. Seriously, you needed that walkthrough…

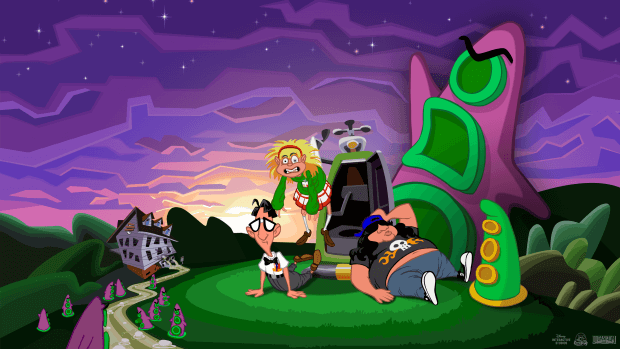

As with any successful cartoon, the characters were endearing and nicely developed – Bernard, a booksmart sort-of-leader; Hoagie, an overweight, hairy music enthusiast who I would one day morph into; and Laverne, a medical student who seems perpetually bewildered by the world around her and who every girl I dated throughout my teens and twenties would remind me a little of – I guess this game seeped into my life in many ways.

The supporting characters were also well-conceived. The Edison clan (originally a family of brainwashed villains from the previous game) are now semi-allies, although in Tentacle you cannot die, so pretty much all the characters have some function or other that you need to harness to move the story along; they are essentially props with well-written dialogue. The different time periods and connections between peripheral characters add a somewhat Blackadder-esque touch to the game, descendants of historical figures such as Ben Franklin and John Hancock identifiable as gag-gift salesmen in the present day, for example – not to mention the various generations of the Edisons themselves.

Another crucial contributor to the game’s overall environment – as, again, with any decent cartoon – was the music, which was expertly orchestrated and timed, and yet the factor that dates the game the most (it is a feast for the ears if you can get passed it being General MIDI).

It’s tempting to simply list all the quotable dialogue, ingeniously-crafted puzzles and twists that made the game such a work of art, but neither you nor I have that kind of time. Well, okay, you probably don’t. However, thanks to that ever-resourceful archive of pop-culture that is YouTube there are plenty of clips to be found, including creator Tim Schafer’s own revisitation:

So far everything you’ve read has been semi-plagiarised from a blog post I wrote nearly a decade ago, and I have to say that all these years later I agree with myself wholeheartedly. The reason for digging out these musings is that I’ve spent the past weekend immersed in the equally endearing world of Day of the Tentacle Remastered, a painstakingly detailed and faithful recreation of the original 1993 offering that will hopefully bring a retro classic to a new generation of gamers and animation enthusiasts.

So perhaps the most obvious aspect to address is – what’s new? Surprisingly little, as it turns out, though blessedly so. Oftentimes ‘remastered’ is synonymous with ‘we added a whole mess of arbitrary crap that we think improves the experience but actually makes the whole affair a bewildering and jarring mishmash of intentions’ – the original game’s association with the name Lucas alone should put people on their guard. Thankfully the tone and atmosphere of the game is 100% intact, in so much as the only immediately noticeable differences are the updating of the graphics to HD and a slight modernisation of the aforementioned soundtrack. I say ‘slight’ as, for the most part, the orchestrations remain gloriously inauthentic and cheesey, though they perhaps have a bit more dramatic impact in certain instances. They remain an assortment of wonderful compositions; the slow jazz and elevator muzak of Bernard’s present-day travails, the military marching-band infused backdrop to Hoagie’s post-colonial wanderings and the low-key sci-fi atmos of Laverne’s tentacle-populated future remain endearing, non-intrusive accompaniments to the increasingly bizarre puzzles the player will find themselves entertaining. When you’re slapping spaghetti and horse dentures onto a mummy so that a tentacle guard can take his wife out on the town leaving you free to throw a fake skunk into a jail cell, a nice tune or two may come in handy lest your brain explode.

As for the graphics themselves, it’s a genuine pleasure to see what was always delightful artwork smoothed over and afforded the detail they always deserved. Some reviewers have made the reasonable observation that enhancing the detail of the sprites themselves has cast a bit of a pall over the fluidity of the animation, which definitely came across as more impressive in its early-nineties, pixellated form. Personally I can concede that this is the case but don’t feel bothered by it – adding some additional frames would make the odd moment here and there a bit more fluid, certainly, but the fidelity to the game’s original warts-and-all limitations keeps everything familiar and truly nostalgic. That the lip sync alone remains just as unsynchronised as it ever was in this era of automation suggests that keeping things as they always were was a purposeful creative decision. This extends beyond the animation itself to some of the vocal performances, painstakingly retrieved from the original DAT tapes of the recording sessions; they are largely brilliant, yet certain instances of stilted delivery remain just as stilted as ever – Bernard’s lamentable Travis Bickle impersonation, for example, or Laverne’s bizarrely earnest plea to young players that they shouldn’t actually microwave a hamster in real life remain just as ingenuous yet, at the same time, just as wonderful for it.

The main treats for fans, and ones that make the price tag of a tenner or so more than worth the price of admission, are the inclusion of an unlockable concept art gallery that boasts some superb sketches and paintings created for the original game that would more than justify an Art Of tome, as well as a creator commentary that is sure to appeal to us old souls who have gone back to the mansion after all these years. Other extras will have varying appeal depending on what degree of gamer you are – the currency of Steam trading cards and unlocked achievements will doubtless have more value to some than others. Perhaps the niftiest inclusion, one that emulators struggled to accommodate during the interim period where retro-gamers struggled to find a means of running their old CD-Roms, is that of the original Maniac Mansion itself, which served as one of the earliest video game ‘easter eggs’ should you decide to kill some time on beleaguered stamp enthusiast Ed Edison’s old PC. As before, you can revel in what’s now an even larger visual disparity between the two and get your retro-game on within the retro-game itself. It’s full-on Inception up in here.

In short, if you’re expecting an all-out CG revamp extravaganza of a game that will sit inconspicuously alongside 2016’s most recent offerings, then you’ll be disappointed – but you’ll also be a bad person who should feel bad all of the time because you’ve completely missed the point. If, however, you’re up for an experience that encapsulates a classic era of gaming that only strives to modernise it to the extent that you won’t get MIDI-induced tinnitus or a 320×200 resolution migraine, then Day of the Tentacle Remastered is for you. Plus you’ll get some chuckles to boot.

In summation I’ll renew my own self-plagiarising: The original game was a huge influence on me, if for no other reason than it sparked a desire to create my own cartoon universes with my own characters. Eventually when I got my sea-legs, drawing-wise, a lot of visual derivations started to appear and, during my animation studies, had me wondering whether my generation would be the first to actually count the art of video games as a legitimate creative influence.

Thanks then to the team who took the time to bring it back to the public consciousness – I’d urge anyone with an interest in animation history to give it a whirl as I honestly consider it to be a frequently-overlooked milestone.

Day of the Tentacle Remastered is out now from Double Fine for PS4, PS Vita, Mac and PC