The Animated Worlds of David Lynch

The art world was dealt a pretty brutal gut punch last week, with the unexpected news of the incomparable David Lynch’s passing. While recent updates had indicated, with some sadness, that his filmmaking days were likely behind him due to an emphysema diagnosis, there was no indication that he’d be leaving us quite so soon (indeed, mere days before his death, discussions of the Greater Los Angeles wildfires saw close associates report that he was safe and well).

The heartening part of when someone as influential as Lynch passes away is seeing the wealth of incredible artists voicing how important to their own work and journey he was. It came as little surprise to see just how much the animation community has been affected, and while it may not be what he’s most remembered for, Lynch’s own enthusiasm for the medium of animation is a clear and recurring theme throughout the entirety of his career. Just a heads-up now, this piece won’t be an entirely spoiler-free affair – but I won’t reveal who killed Laura Palmer. Frankly, after this many decades, I’m still not entirely sure myself.

A whistle-stop tour (which, alas, is all that my current life and work demands determine this article must be) of Lynch’s more noteworthy dabblings in animation would, predictably, begin with his film student years. While studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, a desire to make his paintings move and a series of happy accidents ultimately resulted in the 1967 installation piece Six Figures Getting Sick (its correct title, as confirmed by Lynch to film writer David Hughes, although it is more often known as Six Men Getting Sick), in which a looped animation is projected onto a sculpture made from several plaster casts of his own head, abstract save for the promised deluge of vomit they all simultaneously succumb to. Good wholesome fun, though reportedly the pitfalls and tedium of it nearly put Lynch off filmmaking altogether.

Thankfully he persevered, and a more involved production that mixes its animation with live-action elements came shortly after in the form of 1968’s The Alphabet. Largely composed of straight-ahead, analogue animation that boasts curiously contemporary mograph sensibilities of a yet-to-come digital era (the formation of imagery, in particular a collage-constructed figure whose face seems borne of a blood-filled phallus, would feel at home alongside the experimental animation of the early 2000s), the piece is intercut with live-action footage of then-spouse Peggy Reavey cavorting in bed, reciting the alphabet and eventually vomiting blood. This same period would see him dabble in an assortment of experimental sketches employing an array of animation and scratch-on-film techniques that would eventually be compiled and released as a supplemental feature on the 2008 Lime Green DVD box-set, titled 16mm.

For The Alphabet‘s minimal production values, the stamp of the artist is immediately visible, and it is peppered with jarring moments that give it the unsettling edge he would grow to achieve mastery of. It would also be a significant stepping stone on the path to studying at the AFI and the beginnings of his feature film career. On that note, the nightmare masterpiece Eraserhead, his 1977 debut feature that would sometimes be paired with Suzan Pitt’s Asparagus during its theatrical run, even sprinkles in some cheerful stop-motion business in amongst its practical effects.

If that seems a little odd, rest assured it makes complete sense within the context of the film.

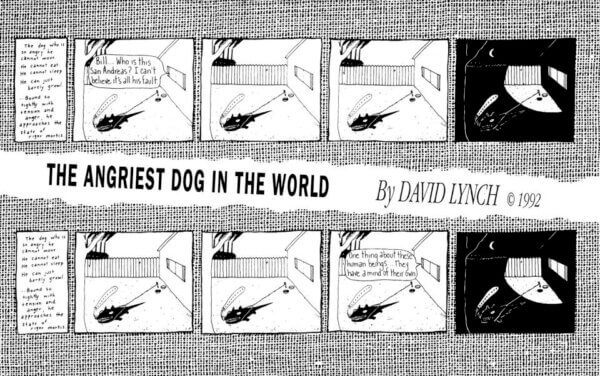

Although not animated, I’d be remis to not include mention of Lynch’s comic strip The Angriest Dog in the World. Making its debut in 1982 in The LA Reader and running, intermittently, for the better part of the decade, each four-panel strip would present the reader with the exploits of its titular canine – or would, if it wasn’t paralysed with rage. As such, every strip is basically identical, save for occasional musings coming from the nearby window. Such self-inversion of a project’s medium would similarly present itself in later endeavours, including his 2002 live-action “sitcom” Rabbits, in which a script ostensibly comprised of garbled non-sequiters (or are they? Eh? I don’t know, maybe) is met with raucous canned laughter.

While I could write all day on the cultural phenomenon of Twin Peaks and many of the audacious approaches taken during its production, its original iteration proved to be fairly devoid of animation save for the odd bit of charmingly-shonky 90s VFX and that bit where Joan Chen made a right knob of herself. I have to show some love, however, to the vanity card that would punch you in the face at the end of every episode’s credits sequence:

Presumably animated by Lynch himself, these few seconds of shrill, stop-mo brutalism were a consistent reminder throughout the series of the man behind it all, calling back to the rawness of his earlier work, the hands-on approach to his craft and the inscrutable role that electricity plays in his work, a theme that gave the world this glorious moment.

Around this time, Lynch would find himself taking on more commercial work, sidestepping the concern most artists have around compromising their artistic integrity by making ads that were just as out-there as his personal projects. One high-profile commission was an ident for Michael Jackson’s Dangerous album/tour. The short piece combines stop-motion with digital elements in a manner that sets up much of his later work, such as his various web projects and the highly stylised VFX of Twin Peaks: The Return, which we’ll get to in a minute.

Similarly augurous visuals would be seen in spots for Alka Seltzer and Adidas (1993), with 2000 seeing Lynch produce a spot for Playstation (a personal favourite) as part of their PS2: The Third Place campaign, in which Jason Scheunemann wanders, MacLachlan-illy, through a hallway of densely-packed Lynchian madness. While predominantly live-action, the one-minute spot warrants mention for its judicious use of animated VFX, topped off with a talking man-duck. Having never owned a PS2, I cannot speak to how it represented the experience of owning and playing one, but I’m gonna hazard a guess and say ‘not a lot’. The ad would be broadcast in both colour and black and white, the best online version of the latter I can find capping off this rather nifty making-of video:

As an animation-themed sidenote, other commercials in the same campaign are often still attributed, erroneously, to Lynch, including one that repurposed UK director Tim Hope’s fabulous The Wolfman.

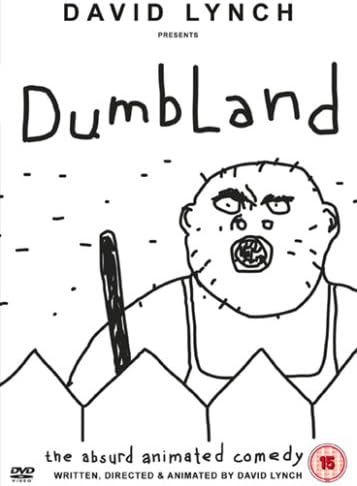

A credit to Lynch was his ability to go with the times in a way that meshed well with his artistic vision. For some years, exclusive content and merch was offered on his official website behind a paywall to ardent fans such as I, among them daughter Jennifer Lynch’s podcast (before ‘podcast’ was even a word) Oddio, the aforementioned Rabbits, music, interactive components, DV film experiments that would sew the seeds of his 2006 feature Inland Empire and – most germane to this piece – an entire eight-part Flash animated series titled Dumbland. Initially created for shockwave.com, back when acerbic animation was part of its manifesto, the series was described by Lynch himself as “crude”, “dumb” and “very bad quality” – and delivered on all those fronts.

With a similar energy to The Angriest Dog in the World, the series is centered on a man perpetually seething with rage, usually at his own cost. Tonally, it is at complete odds with Lynch’s outward facing persona as someone fairly tranquil (unless you try to get him to shorten a scene with Amy Shiels) and steeped in the practice and culture of transcendental meditation. As far as the visuals go…well, I’m guessing he didn’t read Survival Kit cover to cover. But whether or not it’s your cup of the 48-hour blend, it’s clear he’s having an enormous amount of fun with it.

With a similar energy to The Angriest Dog in the World, the series is centered on a man perpetually seething with rage, usually at his own cost. Tonally, it is at complete odds with Lynch’s outward facing persona as someone fairly tranquil (unless you try to get him to shorten a scene with Amy Shiels) and steeped in the practice and culture of transcendental meditation. As far as the visuals go…well, I’m guessing he didn’t read Survival Kit cover to cover. But whether or not it’s your cup of the 48-hour blend, it’s clear he’s having an enormous amount of fun with it.

Following Inland Empire, it felt as though things were a little quieter on the Lynch front, though one should mention both his live-action/animation hybrid short Absurda (a two-minute panic attack of a film, later released as Scissors) and his decidedly unexpected recurring role as Gus the bartender in Seth MacFarlane’s short-lived Family Guy spinoff The Cleveland Show; he’d later appear in Family Guy as himself in the 2016 seasonal segment How David Lynch Stole Christmas.

2017 saw the broadcast of his magnum opus – the divisive, confounding and bewilderingly brilliant Twin Peaks: The Return. Coming roughly 25 years after the original series’ run, it did the unthinkable by – horror of horrors – being its own thing and not a retread of what had come before. To be fair, if what you liked about the original show was its premise of a quirky FBI agent and a down-to-earth local Sheriff solving spooky mysteries, you’d be entitled to your disappointment when you tuned in to find one of them wandering around in a near-catatonic daze for most of this series and the other absent entirely. But if you were champing at the bit for something that would essentially amount to David Lynch: The Show, you were in hog’s heaven. I was in the second group. Phew.

One of the more popular critical reads of The Return is that it is a purposeful criticism of nostalgia, pointedly deciding to give the audience something contrary to any expectations they might have built up. For the average Twin Peaks fan, this theory holds water – to the Lynch fan, it falls apart completely; it’s a complete nostalgia fest, every episode brimming with callbacks to his prior films, artworks and experiments. Among its more unapologetic qualities is its approach to its animated VFX sequences, which truly stand out as not quite like anything that’s come before or since.

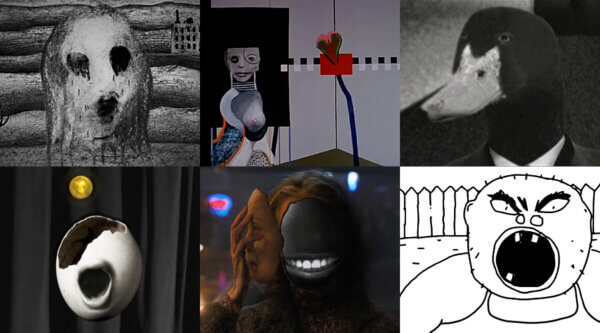

A fair percentage of its VFX is taken on by the enormously capable French studio BUF, handling – for lack of a better term – Lynch’s more ‘photorealistic’ demands that include complex CG animation, de-aging FX and one of the most audacious and extraordinary sequences in television history (more on that in a bit). Alongside these are instances of on-screen animation that give the notion of any suspension of disbelief a good kicking. Usually taking place in the show’s otherworldly Red Room – a fugue where time has no meaning and characters communicate in cryptic, reverse-phonetic riddles – the hyper-unreal, possibly faux-naive sequences are instantly identifiable as being hand-crafted by Lynch himself (though, given the similarity of their movement style to her other collaborations with the director, might have been crafted by animator Noriko Miyakawa, credited on the show as Assistant Editor), sometimes overlaid on top of shots BUF delivered initially. A standout example being a particularly WTF moment in which grieving mother/widow-turned vessel of cosmic evil Sarah Palmer rebuffs a gammon-ey trucker’s advances by peeling open her face before tearing out his throat (I said there’d be spoilers). BUF’s first pass, as per their FX reel, is pretty decent piece of business in its own right:

The version as broadcast, however, fills Sarah’s face-void with a veritable showreel of unabashed Lynchey After Effects insanity, one that nods to his 2013 artwork series Small Stories:

The starkness of the unblended assets and their jagged, unnatural motion paths would, by this episode, be a familiar sight to viewers. Series protagonist Agent Cooper’s visions – that guide him through several days where his brain function has been wiped – possess a similar flatness. Occasionally we would see the life cycle of a tulpa (a kind of clone, long story) come to an end in a manner reminiscent of the death animation at the end of a SNES boss battle:

While they perhaps come across as cheap to your common or garden variety TV watcher, to those who’d been following Lynch in the interim, they cheerily sit alongside the visuals of a slew of prior commercials and artistic projects, such as Rabbits, Inland Empire and Dream #7, a contribution to the 2010 anthology 42 One Dream Rush, later released on its own as The Mystery of the Seeing Hand:

Given Lynch could have easily charged BUF with a more conventional approach to these sequences, one would have to assume their absurd ‘fakeness’ is a deliberate style choice, one that wrenches you out of the action and slaps you with the message “this is not real” (or perhaps “we live inside a dream”). The visuals have confounded industry professionals and part-inspired enormously lengthy critical dissections of the show as a whole, and interpretations of their meaning remain a popular discussion point on forums some seven-plus years since their original broadcast.

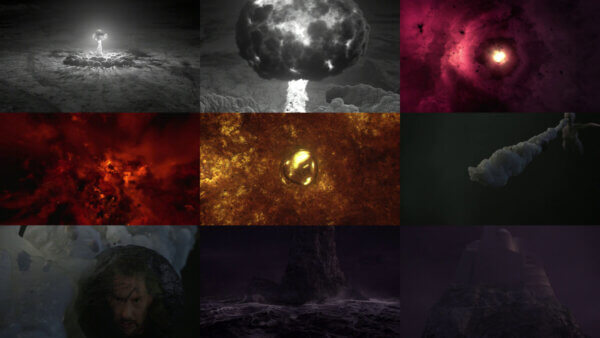

Back to BUF, the moment in Twin Peaks history that nobody saw coming was the flashback origin of its intangible villain BOB – either a supreme manifestation of ‘the evil that men do’ or the ghost of a really nasty twat in a jacket. Making a case for the former, episode 8 of The Return halts proceedings out of nowhere and takes us back to the Trinity nuclear test in 1945. In a sequence that flicks the Vs at Oppenheimer, we’re treated to a 10-minute showcase of some of the most lavish experimental animation a TV show has ever attempted (and not that many films have pulled off, frankly). While inviting comparisons to similarly audacious moments in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life, it perhaps most heavily calls back to Lynch’s own compilation of 1968 film experiments 16mm – right down to the musical accompaniment of Krzysztof Penderecki’s harsh string arrangements.

The sequence is a celebration of artistic chaos that TV critics either lauded or didn’t know what to make of. Described by OIAF’s Chris Robinson as “undoubtedly the greatest work of art [ever] made for a television (or computer) screen”, Liz Shannon Miller of IndieWire would liken it to “the sort of beautiful nonsense best enjoyed on a loop in an art gallery while sipping cheap red wine”. Whichever way you slice it, it makes for a damn good reel piece.

Amongst whispers of another long-form project on the horizon (that sadly never came to be), following The Return Lynch would continue to offer up shorts such as the absurdist Netflix offering What Did Jack Do?, web experiments, HD re-releases of earlier work and various spots tied in with his musical endeavours. 2020 would see the online release of what may be considered his final animated film, a short titled Fire (Pozar) from 2015. With assets and environments drawn by Lynch, the film is animated by frequent collaborator Noriko Miyakawa with music by Marek Zebrowski. Its intent typically mysterious, the piece doesn’t so much tell a story as offer up a series of turbulent imagery – a man forebodingly strikes a large match, seemingly setting off a chain events that include the arrival of a strange wormlike creature through a portal in the sky, a house and tree engulfed in flames, a parade of deer-like entities dancing on their hind legs and an onlooker weeping in despair. In a full-circle sense, it feels very much in line with Lynch’s intentions at the very start of his career in its uncanny infusion of life into his paintings.

While we’re unlikely to see the likes of David Lynch again (though I’m sure the steady stream of imitators won’t abate any time soon), it remains a blessing that he has left behind such a volume of work; that this article has barely touched upon his paintings, sculptures and music, not to mention some of the most significant films of his career, is testament to just how prolific the man was. It’s been a hard task indeed to reign in my impulse to Lynchsplain all of these strands of his brilliance and keep this to a 3000-worder just on the animation. But I hope this small glimpse at the man’s unfettered creativity and passion for his art prompts some of you to go down the Lynch rabbit hole. It is a place both wonderful and strange.