Danny Elfman’s Music From the Films of Tim Burton – Review

Birmingham NIA, 10/10/2013

In all likelihood, a live music event is not the most expected review subject for Skwigly readers to be presented with. Though given that so many great films – from student and auteur shorts to major motion pictures – owe a sizable percentage of their success to the music that bolsters the emotion behind them, it’s perhaps not so surprising.

If there’s one composer of note that justifies coverage from an animation magazine it’s Danny Elfman, the man whose work is being celebrated throughout October in a series of live performances focusing on his nearly 30-year creative union with Tim Burton.

On the offchance that you’re not aware of Elfman’s work – actually, I’m going to stop myself there; You most definitely are. Between his staggeringly prolific output, the multitudinous commercial outlets his various film scores have been licensed for and the fact that he’s written the most well-known TV theme song next to a certain, now-unbearable Rembrandts number, the statistical probability of being exposed to the man’s music in some form or other is through the roof. An active film music composer since the early 80s (and a highly-coveted one since not long after), the film genres he’s tackled run the full gamut, from oddball comedy to psychological thriller, fantasy to romantic drama, sci-fi to horror and pretty much everything that comes between. Yet despite making his mark on over ninety films and counting, it’s the work produced when paired up with Burton – a comparatively small percentage of his output – that he’s perhaps best known for. Aside from a brief separation during the 90s, the two have notoriously interwoven their respective crafts to tremendous, humorous, macabre and, at times, quite moving effect.

A similarly gushing intro to the one above from BBC Concert Orchestra conductor John Mauceri begins proceedings, which predominantly entail live performances of specially-arranged suites representing all of Burton and Elfman’s major film projects, set at times to a backdrop of clips and concept art. As soon as the music plays I’m reminded of the opening scene of Red Dragon – a movie coincidentally scored by Elfman, though not directed by Burton – in which Anthony Hopkins as the cannibalistic sociopath Hannibal Lecter stares, enraptured, amongst the audience of a classical music performance, until a flautist botches a crucial note; In the subsequent scene the offending musician is being served to symphony board members as an hors-d’oeuvre.

Not to be too grim about it, but this sequence best represents my mindset as, at his best, Elfman is to me as Mendelssohn was to Lecter. In short, if any of the BBC Concert Orchestra botches one goddamn note, they’re going in a quiche.

Worries of this nature quickly prove themselves unfounded, to the extent that the mistakes are so nonexistent and the musicianship so finely executed that at times it doesn’t seem like a live performance at all. The keen of ear can, however, pick up a variety of reconfigured arrangements and instrumental change-ups to keep things interesting, though the more celebrated cues remain largely untampered with.

For the most part, the films being showcased are live-action, combining the highs and not-so-highs of Burton’s cinematic endeavor. There’s the obvious – his two commendable stabs at the Batman franchise are conveniently rolled into one extended suite which makes judicious use of Elfman’s signature brass riff, one that became synonymous with the titular superhero for many a year – along with his notorious penchant for gothic adolescent-bait such as Sleepy Hollow and Dark Shadows.

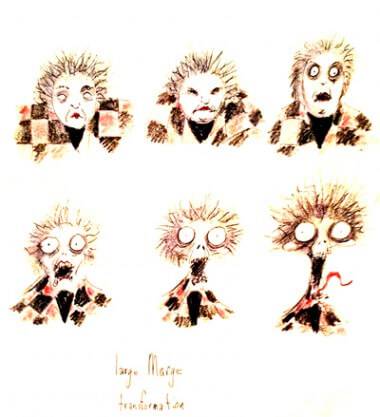

Earlier work such as Pee Wee’s Big Adventure (during which we’re treated to Burton’s early sketches of Large Marge, a woman who ruined an entire generation’s worth of children’s underpants including my own) and Beetlejuice are given fleeting consideration, a tad disappointingly in the case of the latter as it serves as a standout example of an early, somewhat staccato-dependent style and Danse Macabre-esque string sections that would later be built upon. Also given mere nods are films that weren’t quite so well-received, such as Mars Attacks which offers a fabulous theremin (an instrument described with farcical inaccuracy as “some kind of xylophone” by the young lady seated behind me to her companion) performance from Lydia Kavina. Also representing the mildly lambasted is Burton’s misjudged 2001 Planet of the Apes remake whose fabulous, percussion-driven Elfman score surprisingly doesn’t gel quite so well with the NIA’s acoustics.

Of course it’s the animated features that warrant special Skwigly consideration, and the arrangements put together for both Corpse Bride and Frankenweenie are predictably harmonious and playful, though irrefutably the work of an older, more sophisticated and mature composer. Despite not being nearly as infused with Thomas Newman degrees of melancholia as, say, Big Fish, they’re sadly missing the childlike frivolity of his late 80s/early 90s work which had yet to fully shake off the carefree goofiness of his Oingo Boingo days. As charming as that combination could prove to be, the most crowd-pleasing reminder of how his earlier work could be both haunting and beautiful comes, naturally, with Edward Scissorhands. Though boasting perhaps the most recognisable works of Elfman’s career, what makes it such a masterful soundtrack is its simplicity. The opening credits suite and grand finale that bookend the bizarrely charming events of the film itself are made up of fairly basic chord progressions and orchestral arrangements – strings and choir lead the way for the most part – so when both hit their respective crescendos it is entirely dependent on the pure, human passion of the musicians behind it.

With that, the true highlight of the evening unfolds, met instantly with excited murmurs of approval. An extended selection of musical numbers from The Nightmare Before Christmas (the one film of the night to have been only produced, not directed, by Burton) is clearly what the evening has been building towards, and with the film celebrating its 20th anniversary concertgoers have been promised an onstage appearance by Elfman himself.  Said appearance does, in fact, extend to not merely treating us to a song from the film, but every song led by the movie’s nearsighted protagonist Jack Skellington, for whom Elfman provided the singing voice. From the strained, aching yearnings of Jack’s Lament to his post-failure redemption anthem Poor Jack, the audience is left giddy with enthusiasm. Twenty years on, his vocal performance remains so identifiable as that in the film itself that the whole experience seems a little bit unreal. It’s perhaps for this reason that, when the evening’s single hiccup comes in the form of his enthusiastically coming in on What’s This? a half-bar early, the audience responds with joyful cheers and rapt applause that almost suggests relief; His fallibility is welcome as, without it, the evening would come off so perfect as to be vaguely unsettling. All told it is a truly magical show, one that might only have been topped had Catherine O’Hara been brought out to perform Sally’s Song (something Helena Bonham-Carter was reportedly coerced into when appearing alongside Tim Burton for the tour’s opening London show – neither made an appearance tonight). Instead we’re treated to an encore performance, including the soprano-led theme from Alice In Wonderland and an unabashedly gamesome rendition of Oogie Boogie’s Song, with Elfman taking up Ken Page’s role as Oogie and conductor Mauceri, bedecked in the appropriate headwear, as the plaintive Santa.

Said appearance does, in fact, extend to not merely treating us to a song from the film, but every song led by the movie’s nearsighted protagonist Jack Skellington, for whom Elfman provided the singing voice. From the strained, aching yearnings of Jack’s Lament to his post-failure redemption anthem Poor Jack, the audience is left giddy with enthusiasm. Twenty years on, his vocal performance remains so identifiable as that in the film itself that the whole experience seems a little bit unreal. It’s perhaps for this reason that, when the evening’s single hiccup comes in the form of his enthusiastically coming in on What’s This? a half-bar early, the audience responds with joyful cheers and rapt applause that almost suggests relief; His fallibility is welcome as, without it, the evening would come off so perfect as to be vaguely unsettling. All told it is a truly magical show, one that might only have been topped had Catherine O’Hara been brought out to perform Sally’s Song (something Helena Bonham-Carter was reportedly coerced into when appearing alongside Tim Burton for the tour’s opening London show – neither made an appearance tonight). Instead we’re treated to an encore performance, including the soprano-led theme from Alice In Wonderland and an unabashedly gamesome rendition of Oogie Boogie’s Song, with Elfman taking up Ken Page’s role as Oogie and conductor Mauceri, bedecked in the appropriate headwear, as the plaintive Santa.

What this evening and those in the tour that preceded it managed to achieve perfectly was a marriage of past and present, a glimpse of a spectacular creative journey that will surely have as many peaks and valleys ahead of it as are behind it already. The Burton and Elfman of old are no longer with us, having been replaced by older, wiser, considered craftsmen, less cut-and-dry, arguably more divisive; But while the past – as L.P. Hartley famously opined – is no doubt a foreign country, it’s well worth the ticket price to go back and visit it every once in a while.