Ari Folman’s “The Congress” – Review

As mentioned in yesterday’s overview of Les Sommets du Cinéma d’Animation, which took place in Montreal last week, the opening film was the subject of much discussion in the days that followed. Directed by Israeli filmmaker Ari Folman, whose prior feature Waltz With Bashir was a deservedly lauded piecing-together of his forgotten experiences during the Lebanon War, The Congress marks a significant shift in artistic direction. While Waltz drew upon autobiographical elements that effectively spun into an animated biopic/documentary fusion, this film is the latest of a long string of hypothetical dystopian visions cinema has been offering up at an increasing rate, though its basis seems more the weakness of humanity than our greed or lack of resourcefulness.

Set in the US with a cast led by Robin Wright, the metaphysical storyline seems familiar and strangely alien all at once – tonally the film is rather reminiscent of Cold Souls, a modestly-distributed film by Sophie Barthes in which Paul Giamatti (who also appears in The Congress as the paediatrician examining Wright’s afflicted son) plays a version of himself keen to enlist the services of a ‘soul-storage’ company and improve as an actor. That film was seemingly an attempt to capture the vibe of screenwriter Charlie Kaufman during his collaborative days with Spike Jonze and Michel Gondry roughly a decade ago; Though not universal crowd-pleasers, efforts such as Being John Malkovich and Adaptation took meta-storytelling to an accessible place without completely alienating their audience. What Cold Souls also drew upon were elements of the ripple effect that led to the Kaufman/Gondry collaboration Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (which demonstrated a new breed of informal, laissez-faire sci-fi), Gondry’s solo effort The Science of Sleep (exploring the blurred lines between fantasy and reality through combining animation and live-action) and the distinctly less-penetrable Kaufman endeavour Synecdoche, New York (an exploration of limbo and death through a bleak, psychological fugue). In many respects The Congress draws on these same elements – the invented technology which sets up the first act, the struggles of a performing/creative artist as a case study midst a devolving society, the increasingly hypnagogic narrative – though its overall agenda seems bound to a greater cause.

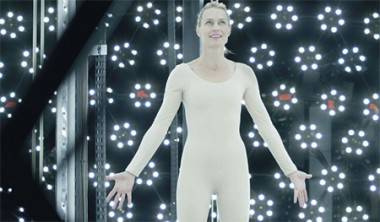

The film’s first act sets up the premise in live-action, wherein a fictionalised incarnation of Forrest Gump/House of Cards actress Robin Wright is castigated for her fickle reputation and unwillingness to play ball within the studio system. Her final offer before being blacklisted is to buy her life of relative obscurity back and have herself digitally replicated as computer data for the studio (dubbed Miramount, a little on-the-nose) to essentially use as a CGI puppet, indistinguishable from the genuine article. These live-action scenes are patchy, boasting many accomplished players such as Wright herself, the aforementioned Giamatti, Kodi Smit-McPhee (who keen-of-ear animation enthusiasts may recognise as the lead in Laika’s ParaNorman) and Harvey Keitel, yet there’s an oddly stilted quality to their performances. The expositional dialogue suffers also from same-writer syndrome, in the sense that all characters regardless of age, gender or background speak with an identical degree of verboseness. Standing out from the crowd in this respect is Danny Huston as Jeff, the wonderfully repugnant studio exec who proposes Wright’s final contract – in both real and animated form, his is a particularly authentic brand of villainy.

In spite of the kinks, whatever their cause may be, there are plenty of appealing and successful elements that, for their sparsity, are appreciated all the more; two in particular are monologues from a mostly-offscreen Keitel, which bookend the first act before the action jumps forward twenty years. With her contract about to expire, Wright accepts an invitation to Miramount’s Futurological Congress where a new technological/pharmaceutical development is in effect; In this world people have the option of living in a self-induced hallucinatory state where people can become whoever they want (albeit as a Fleischer-style cartoon character). Meeting again with Miramount CEO Jeff, Wright is offered a contract extension to sell her very essence so that the general public can use her as an avatar, of sorts. Having entered the same ‘animated’ world, the delineation of the fantasy/reality border becomes a lot more vague from this point on, for both Wright and the audience.  It’s difficult to say which of the characters introduced after this point are real or imagined, or whether or not that should even be a concern; What little investigation I’ve managed of the credited source material, Stanisław Lem’s The Futurological Congress, would suggest not. There is definitely a cautionary tale buried amongst the unrelenting parade of colours, shapes and shouting, one decrying an eventual cultural dependence on pharmaceuticals, but it seems almost tacked-on. Least explicable of all is the introduction of Dylan (Jon Hamm), a man claiming to be Wright’s CG alter-ego’s animator who has become obsessed with her, prompting a bizarre love story that doesn’t quite land. Additionally there’s an undercurrent of hostility and foreboding, even during the rare moments of placidity, cultivating an atmosphere most reminiscent of Ralph Bakshi’s maligned Cool World.

It’s difficult to say which of the characters introduced after this point are real or imagined, or whether or not that should even be a concern; What little investigation I’ve managed of the credited source material, Stanisław Lem’s The Futurological Congress, would suggest not. There is definitely a cautionary tale buried amongst the unrelenting parade of colours, shapes and shouting, one decrying an eventual cultural dependence on pharmaceuticals, but it seems almost tacked-on. Least explicable of all is the introduction of Dylan (Jon Hamm), a man claiming to be Wright’s CG alter-ego’s animator who has become obsessed with her, prompting a bizarre love story that doesn’t quite land. Additionally there’s an undercurrent of hostility and foreboding, even during the rare moments of placidity, cultivating an atmosphere most reminiscent of Ralph Bakshi’s maligned Cool World.

On that note, the animation itself is certainly impressive for its sense of spectacle – there’s little by way of subtlety. Tipping its cap to the fluidity and design style of 1930s animation, the movement is constant, the crowd scenes are bursting and the colour palette would give the most garish CBeebies production’s art department a headache. I’m reminded of an old Frasier line “If less is more, imagine how much more more will be”, and while the length of the average Fleischer short matches up pretty much exactly with the tolerability of such excess, when faced with it for the better part of an hour it becomes almost an endurance exercise.

None of this is to say it’s a film to avoid – on the contrary, I’m rather enthusiastic for more people to see it, as whether or not it succeeds as a longform, narrative endeavour comes second to the dissection and debate it has the potential to prompt. Midst a sea of mainstream animated features that, for all their technological progression and artistic skill, wind up as either ‘kind of good’ or ‘kind of bad’, The Congress will swirl around in your head for a good long while which, in and of itself, elevates it somewhat.

For more on Ari Folman’s The Congress you can visit the film’s official website and Facebook page