‘Cochemare’ – A Conversation with Chris Lavis & Peter Bas

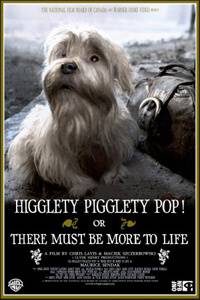

In 2007 Chris Lavis and Maciek Szczerbowski (aka Clyde Henry Productions) made tremendous strides in the art of stop-motion animation with their much-acclaimed NFB short Madame Tutli-Putli. The film’s positive notoriety largely stemming from the application of an inverse ‘uncanny-valley’ effect where human eyes were digitally composited over puppets, it received an Oscar nomination for Best Animated Short Film in 2007. Since then the duo have been actively producing commercial work and continued their relationship with the NFB with the live-action Maurice Sendak adaptation Higglety Pigglety Pop! in 2010. Their latest short Cochemare is a suspenseful, surreal and hypnotic departure for the duo, combining mythology, sci-fi and inexplicable explorations of sexuality. Shortly after the film (scheduled to screen this week at Encounters) debuted at Annecy we were able to chat to Chris Lavis and visual effects supervisor Peter Bas about their bold new direction.

You’ve been working together for a while, correct?

Chris Lavis: From the very beginning. Peter was a student intern on our first film, which was Madame Tutli-Putli. He showed us his reel which, at that point, was him and his friends doing effects from X-Men! It was hilarious enough that we started working together and he was the special effects supervisor on our next film Higglety Pigglety Pop and Cochemare.

Breaking down the oft-discussed ‘eyes’ effect (Madame Tutli-Putli, 2007)

Madame Tutli-Putli really was the talk of the town for a while, with the angle you guys took for the visual effects. Had that been the first time that marriage of techniques had been done?

Peter Bas: I believe so.

CL: The effect was largely the work of another artist we worked with named Jason Walker, who was a portrait painter dabbling in special effects. Then it turned out he was more than dabbling, what he’d learned as a portrait painter turned out to be perfect for that technique. I think it was the first time, the first and last – it’s horribly difficult to pull off.

To get it exactly right, frame-by-frame?

CL: Yeah, it’s basically key-frame animation, the time-mapping was done frame-for-frame, the blending was done frame-for-frame, it took the same time as the animation itself.

What was yours and Maciek’s history, pre-Tutli-Putli?

CL: We’ve worked together since 1997, we spent maybe two and a half years making a comic for Vice magazine, called The Untold Tales of Yuri Gagarin. We basically started as friends at university, shared a studio together and just enjoyed working together. The comic morphed into animation because it seemed like we were already doing sequential storytelling with puppets. To add that next element seemed like the natural step.

For Bas, what was your role on Tutli-Putli?

PB: Well, working with Jason Walker who was basically in charge of all the eye effects – I did everything other than the eye effects! Every shot was heavily manipulated, I would say. There’s a lot of other compositing that goes on, it isn’t just that one specific effect – all the puppet rig removals, backgrounds, green-screen compositing. I believe Chris did some compositing on it as well.

CL: I did a little bit.

PB: Chris is also a masterful compositor.

It’s a great thing to have in your back pocket if you’re an animator already, to know your way around compositing. I imagine it can help in planning shots, knowing what can be done down the line?

CL: Absolutely, yeah.

PB: It’s insanely useful for shortcuts in animation.

CL: I think generally our school of thinking for filmmaking from the beginning has always been to direct films knowing some piece of everything – lighting, building props – direct a thing that you at least have dabbled in. For us it just makes it so much easier, and it’s so much easier to tell if someone’s bullshitting you. In this business it’s so easy to tell a director something is impossible or “That’s not how it’s done” and there’s nothing like having done it yourself to say “Actually, it’s perfectly possible, we’ve done it before”. It makes a huge difference.

(Madame Tutli-Putli, 2007)

You mentioned “first and last” as far as the eye effects – I have seen it subsequently in at least one other film, I was curious as to if you were aware that other people are doing that effect?

CL: I think I saw it in a soap commercial!

PB: Yeah, I saw it recently, I think last year in some kind of a TV ad for something, for more of a comical effect.

CL: To me it also makes sense that, at the time we started making it in the early 2000s, CG eyes were not at its stage yet where they could compete with real eyes…

Which I think, to a degree, there’s still a big chasm between where we are now and getting it exactly right.

CL: And that’s your uncanny valley, which I think is why Pixar decide to not try to, they almost go for glass, puppet eyes as a way of solving that problem. So if you have the technology to do the Hulk in The Avengers, there’s no way you’re doing real eyes, it’s pointless. Whereas for us it was a sort of poor man’s way of creating puppet expression because we could never afford CG. We were always frustrated by that limitation of stop-motion, which is the eyes. You always had to do a certain stylised performance because you could never really look into the character’s brain.

In getting the people to perform the eyes, were they chosen based on the designs of the puppets or were the puppets designed to match the performers?

CL: With Tutli-Putli it all happened together, it was crucial that when we’d shoot reference for the animation it was always the same actor that would later have their eyes put in. There was always that connection.

Now that some years have passed, what’s your own interpretation of how Tutli-Putli ends?

CL: Generally what we noticed when we went to film festivals was people would say “That’s a very confusing ending, very strange. Did X and X happen?” And nine times out of ten that’s exactly what happened, it wasn’t nearly as complicated as some people thought. It ended up being less controversial than when we first showed it; In the first year it made a lot of people angry, and it’s funny how the perceived flaws and failures of a film over time just become less noticeable, whereas when we first showed it at Annecy and Cannes people were really angry! People would say things like “Did you run out of money?” But it’s funny to get that question, I haven’t even thought about either the eye technique or the ending in…six years?

I’ve found that a lot of the films that are most discussed are the ones that generate debate decades after they’ve come out, like stuff David Lynch did in the 80s people still debate about what that meant. And oftentimes there is a pretty simple explanation for everything that, if you like, you can subscribe to so your head doesn’t explode. But when you have a film or directorial technique or symbolism in visual motifs I think people do enjoy the debate and conjecture – “What if this was actually that…” I think it’s kind of nice to have a product that people can see in different ways, even if it’s not necessarily the way it was on paper or in your heads, perhaps.

CL: More and more you learn that that your film’s life has nothing to do with you, even your sense of what its failures are will never be the same as the person who watches it. You’ll find there’s a general consensus about things, and with Tutli-Putli it was the ending and the eyes. That was the theme of most discussion and we didn’t anticipate that. And seeing Cochemare for the first time in front of an audience of strangers I had the same feeling, the film itself becomes a stranger and that’s the moment that it leaves your life forever. That’s the moment you become just another member of the audience.

Are you nervous or excited about how Cochemare will be received?

PB: Well, we’re curious more than anything.

CL: We’re working with a producer in Canada called Phi Films, they’re new for us. They’ve done some very interesting, experimental work, they have a great track record in getting this kind of film out there. For us, even though we’re animators, animation festivals have always been a little bit like a watercolour festival; If you come in and say “Hey guys, don’t you also like oil painting? We can mix oils with our watercolours” They’re like “Eh, not so much”.

It brings to mind a point you brought up when Cochemare premiered, how it and Higglety-Pigglety-Pop had been perceived as being predominantly live-action puppetry when in fact the greater percent is actually stop-motion, is that right?

CL: No, not with Higglety – Cochemare has a ton of stop-motion animation. Higglety has two little stop-motion scenes but no, that’s a live-action movie.

It’s a funny thing, perception. I was in a meeting the other day for this production we’re art directing and one of the producers said “This is live-action, it’s not gonna take months – I bet you’re not used to that”. Actually at this point in our career we’ve made way more live-action that animation in terms of seconds. Even if we’re writing a new script that’s fully live-action we’ll get people saying “I just don’t see it as animated movie” – (laughs) it never was! You get stuck as one thing, it’s very interesting.

It’s one of those grey areas as far as puppets go, “Is live-action puppetry considered a type of animation or not?” and there are different schools of thought, that by making the inanimate animate by puppeteering it’s animation by definition…

CL: Well, they get to do it instantly, for them it’s more of a theatrical performance. You watch it and it’s amazing, but it’s a very different art, a very different craft. But it’s essentially the Frankenstein complex, as Harryhausen said, it’s essentially giving life to the inanimate. And the feeling people have, watching a puppet onscreen, whether it’s a Street of Crocodiles stop-motion puppet or one of the characters in Labyrinth, I think it engages that same part of the brain; The inanimate is alive and there’s something magical about that. What’s interesting is that the culture is completely different, when you work with puppeteers they don’t know animators, they’re not as interested in animation, they have their own culture where they know each other and have a very different sense of puppets on film and what that means. We showed Higglety in front of an audience in Brooklyn – including Heather Henson, Jim Henson’s daughter – who embraced the film in an amazing way and brought us to Brooklyn for a puppet festival. And it’s like I say, they do abstract paintings, we do wildlife paintings, somehow we do not mix, it’s very strange. For me, I’m a decent animator, I can’t puppeteer at all but I like working with those people, it’s extraordinary, so different, really interesting.

We worked with a puppeteer named Marcelle Hudon who was brilliant – in fact, in the latest movie we worked with her again to workshop the scene with the actress. So we had a puppet of the monkey and rehearsed it with Marcelle and I used that as my stop-motion animation reference. We couldn’t use the puppet because it was just technically impossible with greenscreen, also we wanted the monkeys to move in a stop-motion way, that was the proper way of moving them. But the dynamic you have of a puppeteer working with an actor was unbeatable, and just the movements she did and the way that she embodied the character, the way that I as a director could say “Let’s try the monkey doing something like this, why don’t you guys work together and play and improvise with this scene” was really interesting. All of which is to say I think when those cultures combine you can do interesting things, you’re better for it. It’s actually fascinating.PB: When those two mediums collide, as with Cochemare, it makes for some very interesting cinema.

And certainly very different as far as story and theme goes. Although as innocuous as I expect the source material was, there’s a certain tone I found with Higglety that really sold it in an old-timey fairytale way, almost a sinister undercurrent. Was that intentional?

CL: Well, it’s very much in the book. We felt that from Maurice Sendak’s work and were, to a fault, probably too respectful of the source material in terms of our structure and design. You’re right, there’s something creepy as if you don’t want to know the people who made it! (Laughs) Which was strange because the set was a lot of fun and we had a lot of pretty normal people on it. There was something even about showing up sometimes and seeing that cat in his costume, where our puppeteer would be like “I’ve been waiting to see this, I’ve had this as a dream since I was ten to be in a room with this kind of character!” Maybe it was darker than we meant it to be.

Behind the scenes of ‘Higglety Pigglety Pop’ (2010)

Was Maurice Sendak still around when you made it?

CL: He was, absolutely.

Was he involved, or did he see it at least?

CL: When we began the project, Maciek, myself and Spike Jonze traveled to Maurice’s house and spent the day with him. Spike had been working with him obviously for a few years on Where The Wild Things Are, we had a day where we were just there to talk about Higglety Pigglety Pop, what it meant for him and where it came from. Maybe that’s what infused the darkness in it, because Maurice was at a point there too where I think he knew he was running out of racetrack; He was far more cynical and dark about his own work than he had probably been when he wrote it.

So going from that film to Cochemare…how does that happen?

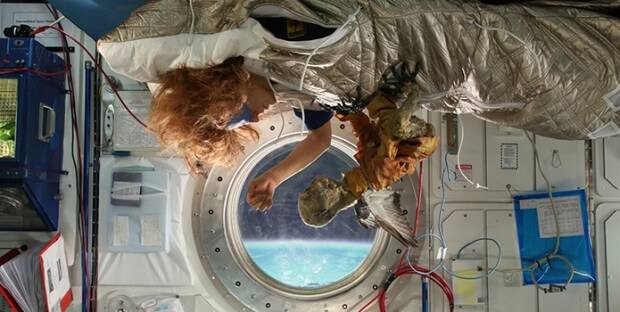

CL: Well, it’s a perfectly reasonable reaction to making a children’s story (laughs) and it was also largely based on the producer Pheobe Greenberg who was the mastermind behind Phi Films. We knew that we would be proposing to someone who would let us go places no-one else ever would and we wrote the story accordingly. We wrote the story for a company where the sky’s the limit, what could that possibly look like? International space station, a forest with storms, strange sexuality – it was the perfect marriage.

Where there any particular influences for the designs of the monkey creatures?

CL: I think before we wrote the story Maciek built the puppet of the monkey, it came from him going to stay in London with Stephen and Timothy, the Quay Brothers. He came back with his mind blown, matched with a depression that we were wasting our lives, that we weren’t being as interesting as we could be. That puppet that came out of that inspiration. It was based on some photos we found of preserved Victorian monkeys and the clothes they were wearing. We based their fur and their whole look on the way they had dried up and mummified and I think from there we thought “What movie do you see this monkey in?”. There was something about them where somehow a film about sexual obsession would be the perfect way to use those, we didn’t see them starring in something for kids. I think because the original impetus has come from the Quays’ studio we wanted to collide that with something completely different, and we came up with the international space station. Suddenly that collision started to be interesting.

Was there any female input in the development of the story?

CL: Very much, we worked very closely and respectfully with the actress who plays our astronaut. We workshopped and rehearsed the scene with a vague idea of where it was going – we knew that she was an astronaut on this space station and that she would be visited by this creature, but we very much wanted her reactions to that situation to be something she as a performer and a writer worked out herself. Of course, as always happens, she took it someplace far stranger and dirtier than we ever originally thought, y’know? Something that was much more psychologically f*cked up than we were willing to go! (Laughs) We really didn’t want the movie to be Emmanuelle In Space, so it was important that it be done in a way that there was some authenticity to the performance, as ridiculous as it was: An astronaut being visited by a demon monkey as she’s sleeping on the international space station!

Was it the same actress in the forest scene? It’s hard to tell with the inverted colours…

CL: No, completely different, we were going for two completely different kind of archetypes. With the astronaut it was kind of based on the paintings of Gustave Courbet, we wanted this sort of voluptuous, golden light, a more maternal beauty. With the forest we were going with that sort of sexless, ageless Dutch renaissance body. We were very much playing with those two, part of the idea was these collisions, and that was very much it, the Courbet with…I forget the Dutch painter, one of the ‘Vans’!

Was your (Bas) role on the film largely the same as with the other films you’ve worked on together?

PB: I would say largely the same as the other films – mainly Higglety. Then you add that other layer on top, which is the 3D stereoscopic element of it.

CL: The 3D was not a possibility without Pete, no question.

PB: It was a whole amalgamation of different elements on this, we had stop-motion, live-action, some CG and heavy compositing all done in stereo, so we went back and forth quite a bit, I feel. I try to help the guys get their vision as much as possible but I think I brought an area of some knowledge in the 3D department on this. And you know, stereo compositing can lead you down a road that is dark, my friend! That being said, I think it worked out pretty well.

Have you done much in terms of 3D before?

PB: Yeah, when I’m not working with the fellas here I’ve worked on some full-length stereoscopic documentaries, a few shot in 70mm IMAX format, so that was amazing. I also did a bunch of conversion work, which I’m not a huge fan of but it was great to bring back some of those tricks on this project as well. I go back and forth with some feature films as well.

So as a viewing experience is it important for this film to be seen in 3D?

CL: I would say so. We were talking with our friend Ron Diamond about how filmmakers can get very myopic about making their 3D film – they get so excited at the beginning they think that’s the only way anyone should ever see it, but it tends to be not nearly as much as the filmmaker thinks. But we really did design this from the ground up as 3D. The slow pacing is so that you can actually explore that space a little bit, it’s as much about you immersing yourself in this world and feeling a part of it as it was plot.

PB: I think the film is a trip, it’s a way out of your head, the 2D and the 3D, I think they’re driven by a great, amazing soundtrack done by Patrick Watson and some sound design by Amon Tobin and I think that’s just a trip unto itself.

CL: The plot is so ridiculously simple and virtually non-existent that basically we thought “You’re a real asshole if you think you could’ve spent ten minutes of your life better than that. You went on a ten-minute vacation!”

Cochemare screens at the Late Lounge this Friday (9pm Watershed C1) and Saturday (9:30pm Watershed C1) as part of the Encounters Festival in Bristol. For more information on the film you can visit the official website. To find out more about the work of Chris Lavis, Maciek Szczerbowski and Peter Bas check out Clyde Henry Productions.