An Interview with Claude Cloutier

Claude Cloutier, whose filmography includes the Genie Award-winning Sleeping Betty (2007) and The Trenches (2010), has recently finished Carface (French title: Autos-Portraits), a new animated short that will be beginning its festival journey as part of the Annecy Festival‘s official 2015 selection this week. Produced at the NFB by Julie Roy, whose recent credits include Tali’s Bus Story, Priit and Olga Pärn’s Pilots on the Way Home and Patrick Bouchard’s Bydlo, Carface continues the tradition of exemplary artistic talent paired with insightful and thought-provoking storytelling. In anticipation of the film’s Annecy debut, we interviewed Claude about his path to animated storytelling from his beginnings as an artist and cartoonist.

For the benefit of some of our UK readers who may not have encountered it, can you talk a bit about your work as a comic artist and cartoonist prior to animation (some of which has been recently reissued), and how this has informed your work today?

I worked as an illustrator and cartoonist for Croc, a satirical monthly that was published in Quebec in the eighties and nineties. I was producing two to four pages of cartoons a month. The editors gave the artists a lot of creative freedom, and that allowed me to explore different styles and formats of bande dessinée. Sometimes brief stories told in two pages, sometimes longer narratives, which were later collected into two volumes published in the early nineties: Gilles la Jungle and La légende des Jean-Guy, which have just been reissued by Éditions de la Pastèque.

What was the catalyst for broadening your work to include animation and directing?

To tell you the truth, making animated films was always my end goal, and drawing cartoons was the means that I hoped would lead me there. And that’s what happened, when Yves Leduc, a producer with the French Animation Studio at the National Film Board of Canada, invited me to direct my first film, Le Colporteur (called The Persistent Peddler in English).

Did your prior artistic knowledge make the transition into animation easier?

Making animated films and drawing cartoons and graphic novels are very similar enterprises. Comics use the language of film: different framings, storyboarding, the notion of elapsed time in the narration… Plus, every graphic style can be used in both media.

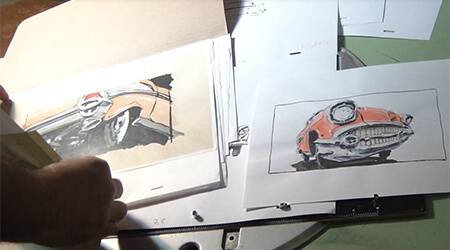

Production art for Carface/Autos-Portraits

At what point did the initial idea for Carface come about, and was it your intention from the get-go to produce it with the NFB?

Along with the films I was making in recent years, I had done a series of surrealist drawings, depicting fossilised characters made up of bones and parts of scrap automobiles. I wanted to use that graphic universe in an animated film, and naturally I thought of making it at the NFB. I knew I wanted the story to be told in song, like an opera or a musical. I was attracted by the idea of an anthropomorphised car, and I had already hit on the idea of lip-syncing with the radiator grilles.

Is there any special significance to Que Sera Sera as the song choice for the film?

I’d searched for years for the piece of music that would lend some meaning to my project; a message. Que Sera Sera struck me as conveying the meaning that I was looking for. It’s full of naïveté, embodying that enthusiastic mindset of the late fifties, with its carefree attitude about the future.

As the film goes on it expands from a simply twist on a musical number to a rather elaborate condemnation of Big Oil. What motivated you to tackle this subject?

I wanted to make a work that would prompt the viewer to think about their social responsibility. To me the automobile is THE symbol of the industrial society we live in, and it reflects the conflicted relationship we have between the joys of consumerism and its devastating consequences on the environment.

Carface/Autos-Portraits (Claude Cloutier/NFB)

On reflection of the completed film do you feel you achieved what you set out to as far as putting the message across?

Well, I hope so!

In terms of the technical execution of the film itself, I understand it’s a blend of traditional line animation with digital colours. Can you expand a bit on the production process and how it benefited the film?

I drew the film using a brush and India ink on paper. The drawings were then scanned and coloured using mask tools in Photoshop, Toon Boom Studio and After Effects. For a long time while making the film, I was hesitant about using colour. I really loved how my images looked in black & white. In the end I went with colour because it’s an element that’s especially evocative of fifties and sixties automobiles and the whole optimistic spirit of that era.

The strength of draughtsmanship and loving attention to detail when it comes to the automobiles and machinery really gives the film a lot of visual weight. Have you always been fond of this subject matter visually?

I’ve always been attracted by science and technology. With this film the main challenge was to make the metallic elements of the subject warmer, more ‘human’. I chose a very gestural, organic graphic style, to try to lend a degree of sensitivity to these objects that are by definition hard and cold.

Carface/Autos-Portraits (Claude Cloutier/NFB)

In anthropomorphising the cars through their movements did you look to any actual dance and choreography footage for reference?

I drew inspiration from a lot of musicals, especially those of Busby Berkeley. I didn’t directly copy any scenes; rather, I tried to recreate the general feel of that genre.

Whilst there is a common mainstay of absurdist humour in much of your other work, films such as Sleeping Betty have also been more narrative-based. Looking back on your filmography from a writing/story perspective do you have a preference for abstract over narrative, or vice versa?

I like exploring styles and genres. I think it’s difficult for me not to incorporate humour into my films. But having said that, I believe that it’s harder to create a comedy film than a drama, and there’s a compromising aspect: a comedy has to be funny, so there’s pressure there…

A film that stands out amongst your recent work as being more sombre is The Trenches. Can you talk through how that film came to be?

At the start, it was a commissioned film, which was supposed to be part of a collection of 11 films about the Great War. I really enjoyed working on that film and, paradoxically considering the subject matter, it was a good deal more fun to make than my comedies.

Sleeping Betty is a prime example of how animation in and of itself can be integral to comedic subversion. Are there any other primary benefits (in satire, for example) of animation as a filmmaking medium you’ve found?

Animation allows you to express anything you want to the viewer by proposing, regardless of the visual style, a novel approach that stands out from live-action shooting. I really enjoy tackling any new project with the idea that I have total freedom: that’s the positive side of blank-page syndrome!

What would you say are the biggest challenges of being a humourist using animation as the medium (and are they different to the challenges of a cartoonist)?

Being pigeonholed as a humourist filmmaker or cartoonist can be difficult sometimes. Audiences always expect you to produce comedic works and some people are disappointed when you do something more serious. The great challenge for the humourist will always be to make people laugh—and, if possible, to do it with originality.

Carface is playing at Annecy this week as part of the Short Films in Competition 2 screening (alongside such films as Robertino Zambrano and Melissa Johnson‘s Love in the Time of March Madness), which takes place today (Tuesday 16th) at the Pathé Annecy: Pathé 1 (10am and 8:30pm) and the Bonlieu Grande Salle (2pm and 6pm); Wednesday 17th at La Turbine (4pm) and Friday 19th at the at the Pathé Annecy: Pathé 3 (2pm). To learn more about the work of Claude Cloutier you can visit his NFB director page.