CG Book Reviews: “Moving Innovation: A History of Computer Animation” & “The CG Story: Computer Generated Animation and Special Effects”

As someone who is attempting a history of American animation covering the period from 1970 to the present, I can confidently say there are any number of serious gaps in our knowledge and understanding of what went on. This is especially evident in regards to computer animation, where most of what’s been written tends to be in the nature of who did what first chronologies. Two rather ambitious books — Tom Sito’s Moving Innovation: A History of Computer Animation (MIT Press) and Christopher Finch’s The CG Story: Computer Generated Animation and Special Effects (Monacelli Press) — have now tried to fill that gap with some success.

The authors come at the topic from different perspectives. Sito is an animation industry veteran (The Lion King and Shrek), labor leader and professor (University of Southern California), who initially turned his passion for history into Drawing the Line: The Untold Story of the Animation Unions from Bosko to Bart Simpson, out of which his current opus emerged (his editor suggested he turn a chapter on computer animation into a separate book). As an insider, he was sensitive to the impact digital technology was having on animation artists, and I clearly remember his warning in The Animation Guild newsletter that its impact would be as great as the coming of sound was in the late 1920s, which is an underlying theme of Moving Innovation.

On the other hand, Finch is a prolific writer of coffee-table books best known to animation fans for his Disney-related works, including The Art of Walt Disney: From Mickey Mouse to the Magic Kingdom and Beyond and The Art of the Lion King. He’s also written on Norman Rockwell, Jim Henson and the history of financial markets. The CG Story seems to be a follow-up to his Special Effects: Creating Movie Magic (1984), written at the dawn of the digital age and one of the earliest popular works on the subject.

Though nominally an academic work, Moving Innovation is written in a popular style of the “It was a dark and stormy night” variety, which I have something of an affinity for myself. (Thus, in describing how abstract animator Oskar Fischinger left Nazi Germany for Hollywood, Sito writes: “Berlin. A cold, gray day in February 1936. A balding man and his wife sat smoking heavily in their chilly studio.”) This style fits in well with his heavy reliance on a voluminous number of interviews with many of the major and minor players in his tale. On the other hand, Finch, whose interviews are much fewer, has a tendency to go for the bigger picture and focuses more on the key players; he does this in a style familiar to readers of making of books (I’ve done one myself) and in some ways not that different from Sito’s. For instance, in discussing the production of Toy Story, Finch rather portentously notes, “Central to this challenge was coming up with a story that could carry a feature-length movie.”

Sito, realizing the intricacies of his story, breaks up his narrative into separate but related threads, including sections on experimental filmmakers such as John Whitney, Sr. (a disciple of Fischinger), US government involvement the New York Institute of Technology’s Computer Graphics Lab. For the most part, he manages to juggle his facts and stories in a very readable fashion; however; while he is good at showing how early computer games drove the early f digital animation, this is not the case with his chapter on the emergence of the video game industry, which doesn’t really connect with the rest of the book.

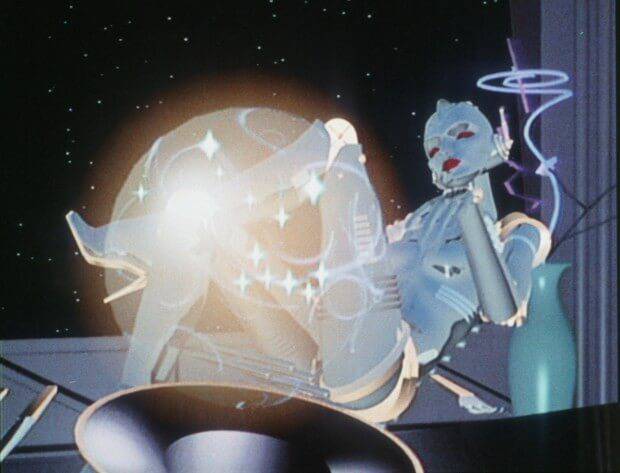

Finch takes a more straightforward approach, settling into a pattern of alternating between chapters on computer animation and those on special effects, supplemented by the heavy use of some spectacular color imagery. Sito has to settle for simpler black-and-white photos, though I enjoyed the many shots of the men and women behind the creation of digital animation at work.

In terms of factual accuracy, Sito manages fairly well given the scope of his enterprise; the errors I did spot relating to his narrative are, for the most part, not major. For instance, computer animation pioneer Rebecca Allen graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design not Brown University, where she only took one class. However, when he tries to embellish his narrative with tidbits of film and animation history, he can be way off. At one point, he notes, “[John Randolph] Bray…made everyone, even Walt Disney, pay for the rights to use [his patents] until his death in 1977 at the age 107”; actually, the Bray-Hurd patents expired in the early 1930s and Bray died in 1978 at the age of 99.

Finch doesn’t seem as error-prone, but there is one point where he and Sito disagree on a point that is worth discussing. Finch repeats the conventional wisdom that Steven Lisberger’s original idea for Tron was to use “backlit animation with CG imagery.” Sito, on the other hand claims, “The original idea was to do Tron all hand-animated with back-lit effects”; and it was only after Allen Kay offered his service after reading about this plan in Variety that Lisberger seriously started to consider digital animation.” Sito’s source is Tron’s animation director Bill Kroyer, who has repeated this version over the years; but one wonders if Sito bothered to double check this by, for instance, finding the Variety story Kroyer refers to ? Where Finch got his information from is often unknown, as unlike Sito, he doesn’t usually cite his sources. This bit of nitpicking unveils how much more work needs to be done beyond relying on personal recollections and studio publicity if a really reliable history of computer animation and special effects is ever to be written.

The CG Story is more limited in scope and seems at times more approachable; in fact, after discussing the pioneering years, it essentially becomes a history of (mostly) American and British animated and special effects films, which is where it deviates from Moving Innovation (and becomes a bit more predictable). Both try to include developments outside of North America, though neither really does a good job of it. Both also ignore the increasing role of digital technology in stop-motion animation in films like ParaNorman, though Finch readily acknowledges the marionette-like aspects of computer animation.

If you want a more scholarly and comprehensive approach, Sito’s your man; one might wish he took a bit more rigorous approach, but it’s evident Moving Innovation will be very helpful to future scholars in the field. However, if you want a less discursive, but still reliable approach, with a greater emphasis on visual effects along with lovely illustrations, then go with Finch.

All Images: Courtesy: The Monacelli Press

Items mentioned in this article: