The Café at the Edge of the Woods | Interview with Mikey Please

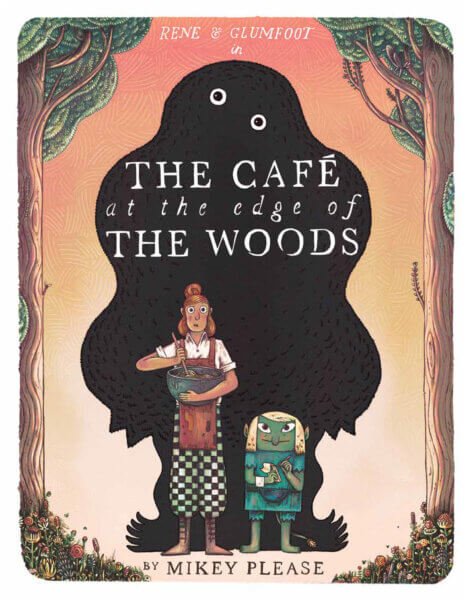

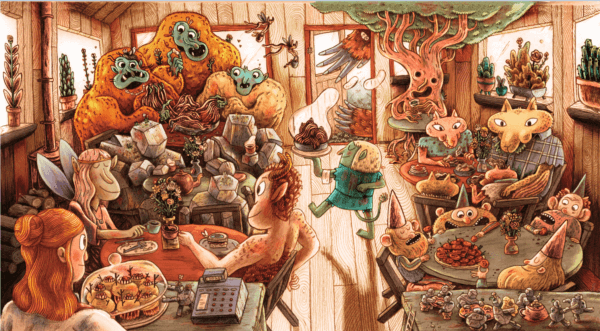

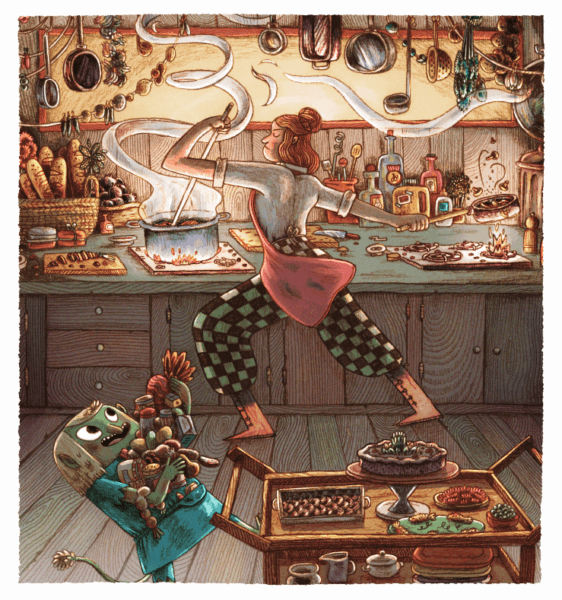

From the talented mind behind The Eagleman Stag, Robin Robin, and Alan The Infinite, long-time pal of Skwigly Mikey Please has unleashed his new children’s book The Café at the Edge of the Woods. A beautifully crafted tale of café owner Rene, who opens up her dream establishment on the border of a magical forest full of folkloric creatures, her desire to serve up the most delicious food is scuppered somewhat by her less-than-refined new clientele, but with the help of newly recruited co-worker Glumfoot a thriving business seems possible.

Inspired by a game Mikey and his wife played with their son over lockdown, the characters have a warmth that comes from living in their creator’s mind, growing over time until they are ready to be released into the hands of others to make their own. There’s a sense of fun and energy to the illustrations, that deliver deliciously textured designs, drenched in autumnal colours. The story has all the hallmarks of a children’s favourite, with cheeky humour and rhythmic storytelling, whilst for adults it holds a contemporary charm that hearkens back to those fantasy-filled games of childhood. The book brings together the talented visual and conceptual skills of this BAFTA award-winning storyteller and takes his passion for the sequential arts into children’s literature. Similar to animated short films, the art of picture books brings together the most nuanced and efficient form of storytelling, and whether through paper or screen, Please can turn his distinct talent to create a wholly intriguing original narrative both succinct and utterly captivating. We were fortunate enough to grab some time with Mikey to learn more about his new foray into visual storytelling.The story of the book is centred around mythical creatures and food, which are my favourite things in graphic novels and illustrations, so it’s totally up my alley. But what was the inspiration for you for the characters and the story?

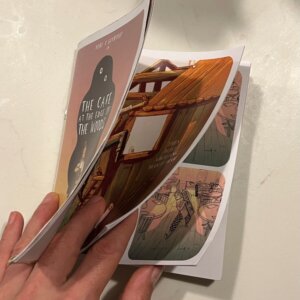

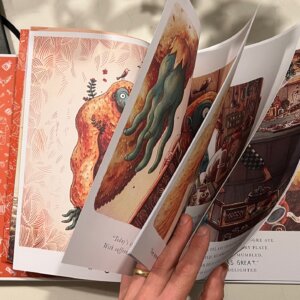

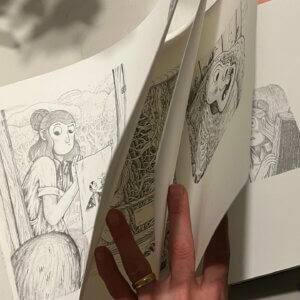

So the the story grew out of this game that, over lockdown, me, my wife and my son would play in the park. My wife would play this pretentious chef who only wanted to serve caviar and frangipanes, and my son would be the downtrodden waiter, like Manuel from Fawlty Towers, while I would play a variety of disgusting or mythical creatures – sometimes a fairy demanding a thimble of morning dew from the grass, or a witch requesting moonlight trapped inside a vase, or sometimes an ogre. It was just a really fun little game that we would play – or a fun game that they would play, and I would interrupt. But that dynamic of pomposity and grotesqueness, and someone trying to communicate between the two was really fun, and there was something really rich there. Then, over quite a long period of time, this little poem grew and grew. It got sort of ridiculously long, so then I kind of chopped it all down and just focused on one customer, who seemed the most fun, or most extreme, which was the ogre. Then I built it up again to really get Rene’s reactions and dig into who she was and why she would feel this way, and treat it more like how I’d create a scripted story. So that’s how it grew over a very, very long period of time of about three years of chewing over it, from playing the game to making a dummy copy (pictured below) which looks pretty similar and the bones of it are there. Working closely with my literary agent Luke, it was about another year or so before officially working with HarperCollins and then another year of making it. I finished it last summer, so it’s been almost a year between me actually finishing the book and it coming out.

- Dummy Book [Image Mikey Please]

- Dummy Book [Image Mikey Please]

- Final Book Dummy Book [Image Mikey Please]

What drew you to want to write a children’s book? Because this isn’t your first children’s book, is it?

Do you think that was because the idea came first and then you realised it would make a good children’s book? Rather than starting with “I want to write a children’s book”?No, Dan [Ojari], I and Briony May Smith made the Robin, Robin picture book adaptation. But that was a different thing. It’s a lovely book, which came out of a story that Dan and I had written, but because it was tied into the film and it was something else already, there was a very different journey with it. I’ve been wanting, trying and failing to write books for probably longer than I’ve been trying to make animation. The Eagleman Stag was a book, it was like a little diary with someone’s last diary entry, that had been scribbled over by what you think is a child, but at the end you realise that it’s actually the main character after he’s had the operation. I did that as a book when I was about 20 or something, so a long time ago, and I thought that’s what I’d be going on to do. Then I realised that animation is a really fun way to translate those stories. But I’ve had lots of various stop-start projects. Dan and I were working on a graphic novel called Dead Rock for a really long time, which we still want to do, we just haven’t finished it. Things have just got in the way, which is madness, because it’s like 300 full A4 coloured pages, which is just an insane volume of work. We’ve just never fully finished it to the point where we could submit it anywhere. But for some reason, I think because of the simplicity and directness of The Café At The Edge Of The Woods, it’s just kind of cut through in a way that the others didn’t. Perhaps because there’s a really clear audience for it as well, whereas lots of my other book projects are a little more idiosyncratic.

Maybe. I think it did come about in a very natural way. I wasn’t necessarily hunting for a children’s book idea. It was just a nice situation. But I do really love children’s books and there’s something about them that is very akin to making a short film, in that they’ve got to be really economically put together, there’s no fat on them and there’s no room for waffling. You’ve just got to go straight to the meat of the thing, you’ve got to get your idea across really quickly, like in a short film. There’s a beautiful succinctness about children’s books when they’re good.

The book is for Axel and Jessica, who are your son and wife. And they were a big influence on on the idea, what do they think of the book?

I think they like it. It’s a lovely thing because, at the moment, Axel is seven and is just the right age to appreciate it. So, I’ve gone to his school to read it to his class which has been really nice. I have wondered, what he’ll think about it when he’s, like, 17, and this depiction of him as Glumfoot. He might not appreciate it so much then! But for now, I think it’s going down well.

The style of the book is unmistakably you. But can you tell me a little bit about how the style has developed and some inspirations that have affected that over the years?

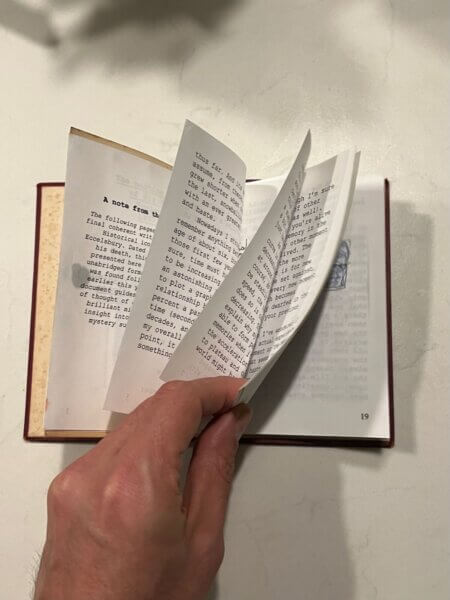

I didn’t really know how I was going to do it, to be honest. Even after I’d signed the deal with HarperCollins, I’d done this rough version, which was just pencil on paper, and then coloured digitally. But I thought, ‘Oh, well, I won’t do it like that. For the final thing, I’ll do paintings’. And I did lots of painting tests, and I did various ink things. I did half a dozen finished style explorations. Then the one I liked best was my rough one, the first sort of scrappy one that I did because it had this direct rawness to it that I loved. It was very important for me that I had an analogue process in there, I knew that I definitely wasn’t going to do it all digitally. I wanted it to have a strong grounding in painting or collage or drawing. Drawing is my favourite thing, so I guess that is why it is in pencil.

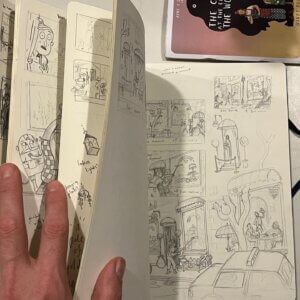

So the roughs were all done in these sketchbooks, and by doing everything in a sketchbook it meant that I could just take it anywhere and do it. As an activity, there was something really attractive about doing that. Recently I’ve come to the opinion that I want to really enjoy the actual minutiae of making the work; I’ve done a lot of projects where I’m like, ‘It’s okay, go through the suffering of this project with the idea that I’ll really be happy at the end of it’. And that’s not a very good way to spend the hours of your life. So it was really important to actually enjoy the process of doing it. That’s why I didn’t do paintings. I would need so many paints, I’d have to set myself up, and there’d be this time stress of the paints drying. It might have looked better, but I wouldn’t have liked doing it as much. I might have gotten very precious or been afraid to make a mistake, whereas having a process that was really direct meant that I could throw it away if I didn’t like it.

- Sketchbook for The Café at the Edge of the Woods [Image Mikey Please]

- Sketchbook page for The Café at the Edge of the Woods [Image Mikey Please]

- Sketchbook page for The Café at the Edge of the Woods [Image Mikey Please]

There are some great testimonials for the book from Jon Klassen and Daniel Kwan, what was it like to receive these compliments from such talented colleagues?

As is often the case with children’s books, it’s quite open, which lets kids sort of build their own stories and ideas about the characters. But as someone who is used to creating these quite expansive worlds for characters to live in through animation, do you feel you have more to tell from Rene and Glumfoot’s point of view, or in a potential sequel or a spin-off project?Those were great. Jon also gave me a brilliant breakdown of the book early on, probably around the draft stage when I made the dummy version of the book. We’d been in communication a little bit about something else, and I was like, ‘Oh, and by the way, I’m doing this children’s book’. He said ‘Oh, cool send it and I’ll have a look’. And I thought he’d just say something nice, but then he sent me this huge breakdown of every page and how to sort of restructure it so it kind of works a bit better, and I followed some of his advice. It was wonderful, such a kind thing of him to do, and somewhere along the way he said that nice thing and let me put it on the back of the book, which is great. Daniel Kwan’s quote is actually from an article in a Netherlands newspaper, which was based on a bunch of talks we and some other friends did for a festival called Playground. Within that was this very lovely thing that Daniel said. I was very touched and he was very happy for me to put it on the back of this book.

Yes, I do. The sequel to the book has already been announced. It’s called The Cave Downwind of the Café. My summer this year has been spent making it, I’m still a little away from completing it, but it’s not a sequel. It’s an equal. So it runs alongside the first, kind of like a companion piece. There are a bunch of other stories involved with them, but so far this second one is confirmed with a release next year. It’s fun doing a second one because I get to correct and improve upon all the lessons I learned in the first one. There’s quite a varying degree of design in the first one, and now having done that book I understand the rules of the characters. So I hope it’ll be a bit more cohesive in this next one.

The Cafe at the Edge of the Woods is available now from all good bookstores. Mikey Please’s next book The Cave Downwind from the Cafe is due for release in 2025.