‘The Boy & The World’ Review

One of the festival highlights of Annecy 2014, Alê Abreu’s The Boy and the World deservedly went home with both the Audience Award and the Feature Film Cristal. Skwigly take a look at the stunningly-designed and expertly told Brazilian film that has had critics and audiences’ tongues wagging.

One of the festival highlights of Annecy 2014, Alê Abreu’s The Boy and the World deservedly went home with both the Audience Award and the Feature Film Cristal. Skwigly take a look at the stunningly-designed and expertly told Brazilian film that has had critics and audiences’ tongues wagging.

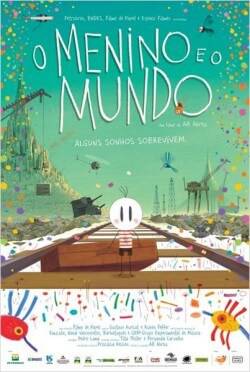

The Boy and the World (2014), or O Menino e o Mundo as it’s known in its native Brazil, is a vibrant, textural, equal parts raucous and tender animated feature film directed by Alê Abreu. Keeping with one of the main trends of Annecy 2014’s feature selection, the film is virtually dialogue-free and relies heavily on it’s fortunately stellar soundtrack. In it’s lack of dialogue it becomes one of those rare animated films, along with the likes of Wall-E (2008), that manages to transcend its cultural boundaries to tell a serious story about growing up, memory, and the pace of change.

The Boy and the World follows the story of a small boy called Cuca as he chases after his father who’s gone to find work in the big city after not being able to support his family working the land of the colourful local village. The story progresses with Cuca running away from home and meeting a variety of spirited characters as he gets closer and closer to the fictionalized metropolis – which has a remarkable amount in common with Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) – dominating the horizon line. After traversing what is essentially the industrialized production process, including an accidental trip on a cargo ship and back, once inside the metropolis we meet the true villain of the film; globalization.

Globalization is represented by everything dark in the film: men in dark suits, a questionably fascist militant authority collaged out of dark images, a figurative bird drawn in charcoal. These forces have deeply affected all the characters we have met thus far, displacing unique individuals from their jobs. In retrospect we realize all the characters have been battling this villain in their own small way through colour. Although a beautiful idea in itself, made more so by the naïve yet enchanting quality of the images on screen, it boils multiple complex ideas down to a simple story that often feels a little heavy-handed in its delivery. This is epitomised towards the end by a minute long video montage that abandons all previous artistic conventions and instead flashes nightly news style clips of mass production, deforestation, and child labor to reinforce its point.

The story is admirable for its conviction and moral resoluteness, but it must be said that this sometimes got in the way of developing any meaningful characters; a disappointment considering how tenderly they had been designed, and an irony considering the story itself strives to celebrate individuality. In spite of this, the film does manage to surprise at the very end with a moving twist involving memory as the story circles back to the colourful village in which it started.

The Boy and the World’s flaws regarding narrative are only notable because the caliber of the rest of the film is so high; If the film is one thing then it is undeniably beautiful. It revels in the analogue glory of paint, crayons, pastels, inks, watercolor, graphite and, later on, collage. The lush marriage of these techniques is plain to see, as the beauty of the images and how they were made are one and the same; Paintbrush strokes, pastel smudges, shading mistakes are all left in, and only serve to further the feeling of a living, breathing world. The film’s real triumph comes when it reduces scenes right down to Cuca and pure white space. This happens often as scenes transition, and is a testament to how grounded in the rich environment you were before and how willing you are to accept whatever is coming next. If you get a chance to see it on the big screen I highly recommend it.

Equally, its soundtrack is excellent. In lieu of dialogue this is where the majority of the storytelling is achieved, through a series of repeating instrumental songs that correlate to specific characters or feelings. Of particular note is the tune that accompanies Cuca’s father, which works seamlessly to embody both the character of the father and Cuca’s point of view when he thinks he see’s him. It will be stuck in your head for days.

Boy and the World (2014) is animated. This is not just obvious, but imperative. By this I mean it could not be made any other way. In the face of a swathe of animated feature films that have embraced the soft side of realism recently – i.e. photorealism with the hard edges removed, see The Croods (2013), Wreck it Ralph (2013) and Frozen (2014) – Annecy 2014 really was about celebrating the seriously hand-made. From Bill Plympton’s crowd-funded pencil and paper Cheatin’ (2014) to the stop-motion of the short film audience award La Petite Casserole d’Anatole (2014) it pushed for films that couldn’t be made in any other medium. The Boy and the World (2014) really is exemplary of this. There is not a great deal of technically complex animation (it could even been called minimal for a feature film) but you feel everything is moving in delicate balance with one another, a balance improbable in any other reality other than its own.

The Boy and the World is a catch-22 of an animation. You feel if more time, or more money, or more man power had been spent on it, some of its rough edges could have been tapered; the bitter taste of poor narrative timing could have been averted. Yet, if it had all those things it would surely loose the things that make it very special; it’s single-mindedness and masterful aesthetic. It was noted at the beginning of the presentation that the charming main character Cuca, with his short movements filled with energy threatening to pop the limbs from his body, came directly from Alê Abreu’s sketchbook. This is what The Boy and the World feels like as a film. It has that same magic as peering into someone else’s sketchbook, seeing their ideas unfiltered, bursting from the page. That alone is enough to make it great.

The Boy and the World premiered at Ottawa International Animation Festival 2013, and has gone on to win both the Cristal Award and the Audience Award for feature film at The Annecy International Animation Film Festival 2014. It is expected to be distributed across the U.S. by GKids and will be among the 2015 Oscar nominations. It is Alê Abreu’s second animated feature film after Garoto Cósmico (2008), which never saw a theatrical release outside of Brazil.