LAIKA’s “The Boxtrolls” Review

A mere two years after Laika released their last ambitious visual masterpiece ParaNorman, we are treated once again to another groundbreaking epic in The Boxtrolls from directorial duo Graham Annable and Anthony Stacchi.

Adapted from Alan Snow’s novel Here Be Monsters! the story follows the residents of Cheesebridge, both the humans on the surface and the boxtrolls below. After a terrible fate befalls a small child’s father, a boxtroll called Fish takes the child and cares for him as one of his own, showing him their way of life, teaching him to craft, giving him his own box and name -‘Eggs’. When he’s old enough they take him on their nightly adventure to the surface to scavenge for junk in the trash of the city. From these forgotten treasures the boxtrolls have built a world of mechanical wonder and invention, but up in the human world all is not well. In a bid to elevate his social status, self-proclaimed Boxtroll Exterminator Archibald Snatcher (Ben Kingsley) convinces the town’s mayor Lord Portley Rind (Jared Harris) that the boxtrolls are in fact horrifying beasts bent on child abduction.

With the trolls’ existence now an unnecessary hindrance to the townspeople, a strict curfew is placed upon them to ensure their safety, allowing Snatcher full freedom to incarcerate and dispose of them. As their numbers dwindle, Eggs begins to wonder if living in fear is the only way to be safe, and when one night on their regular scavenge in the city his adoptive father Fish is captured, Eggs sets about finding and saving his family!

As the film unfolds Eggs must battle with much more than just Snatcher and his crew – he must learn of his own past, his own humanity, who his family are and who he, himself, truly is.

After seeing ParaNorman, I remember leaving the cinema curious as to how one might possibly top (and indeed succeed, as has been Laika’s established track record) the film just witnessed in terms of technique, character and in pushing the boundaries between children’s film and dark, moral storytelling hopelessly engrossed in telling not only the narrative of the story but the story of how a film like this comes to be.

The simple answer is: One doesn’t. The people at Laika seem to be completely content to create what they feel is right and make no qualms of showing the hand-made quality at work in their films (one lovely post-credits touch features a short exchange between Snatcher’s two henchman contemplating the idea of “giants controlling their every move”). Nor do they veer away from the potentially menacing side of storytelling for children and indeed humanity as a whole; They are not afraid to make a villain truly villainous, with all the greed and cruelty that comes with being a broken soul after only one thing. Some of the more sinister characterisations and haunting threats to both Eggs and his family’s lives might indeed prove a little too dark for younger or more sensitive children.

Coraline enjoyed a mild amount of parental backlash in regard to it’s suitability, though parents compelled to take the film’s PG rating on board and watch it themselves before allowing their children to would find much to enjoy. Laika has really upped the comedy factor, with plenty of slapstick and toilet humour to keep the young or the young at heart entertained alongside enough sharp dialogue, innuendo and clever wordplay to give the accompanying parent a chortle or two.

The characters themselves are charming and so swiftly developed you feel you know each of them right off the bat after very minor introductions. The humans are relatable through their brilliantly-animated demeanours alone; Snatcher is the hurt and disgruntled commoner who wants to prove he’s as good as the upper classes and will stop at nothing to ensure respect and adoration from shallow aristocrats such as Lord Portley Rind, a pompous blowhard with an upper-class mentality, profound cheese obsession (as with all of Cheesebridge’s elite) and complete indifference to his daughter. Said daughter Winnie (Elle Fanning), somewhat wanting for love, attention and mainly adventure, finds it in befriending the helpless Eggs, who himself is the story’s typical lost hero, unsure if he is boy or boxtroll; In his struggle to find his true self but never loses sight of what’s really important, his family.

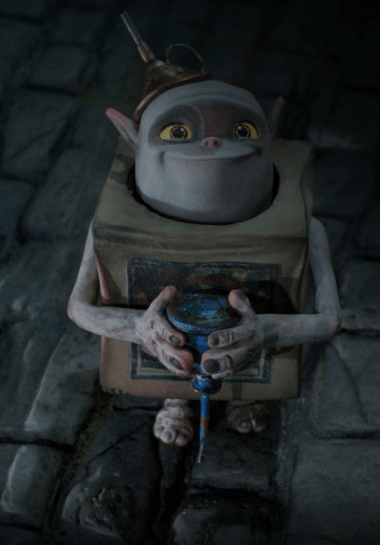

However it’s the boxtrolls themselves who predictably steal the show. While vaguely reminiscent of the minions of Despicable Me with their incoherent half-English and their slapstick humour, in the case of the boxtrolls each one has their own design, character and personalities, headed up by Fish and Shoe (so named after their chosen boxes). There is no explanation behind the origins of this – apparently fully male – society of goblin-like creatures, but their mend-and-make-do attitude as well as their love for Eggs makes them all sweetly endearing (my own personal favourite being Oil Can).

The casting of course can’t be overlooked for its distinctly British flavour – Eggs’ long lost father and Cheesebridge’s finest inventor Herbert Trubshaw is played by Simon Pegg, with Snatcher’s henchmen Trout and Pickles voiced by Nick Frost and Richard Ayoade.

Now down to the most interesting bit – the animation technique. Though it wouldn’t have seemed possible, this film boasts even more detail than its predecessors. It would seem the biggest advance in terms of the overall look of the film would be the altogether more painterly look to the finished puppets. The primary visual link seems to be blues and veins, perhaps as a light nod to the towns fondness to cheese, though overall there are far more natural and neutral tones to the colouring and lighting of this film to give it that Victorian England feel.

The incredible skill of the animator is also not lost in this film. The rapid prototyping used in the faces seemed more noticeable this time around, perhaps due to the even more angular and sharp design of the characters faces or possibly just that, as animators ourselves, we can’t help but search out the details. It is difficult to say much more about the techniques for the film except for that, as you would expect, it’s incredible, the sheer scale of the sets, the volume of puppets as well as costumes and props is something to behold and celebrate. The film has a distinctly European feel to it, both in the pacing of the story and the architecture and style of the world they have created, as well as the ‘found’ quality to some of the design choices, a style of stop-motion favoured heavily in European independent filmmaking. Much inspiration has obviously been taken for this film, but used in a very original way.

It’s sad to see that the film has already generated some criticism (NB Since this review was originally posted the critical response has grown more positive – Ed). While it isn’t breaking down boundaries, it does indeed follow on in terms of overall tone from Laika’s last two features while being different and refreshing enough to stand on its own. It’s precisely the type of film animators, prospective animators and young children will watch and re-watch to let every tantalising detail soak in for hours, days or perhaps a lifetime of enjoyment. That’s what stop-motion offers us – a filmmaking technique which can be experienced in a multitude of ways, with the knowledge that a huge team of people took every loving care over the thing we see, even if for just a fraction of a second.

This is a film not just for the masses but for the very select few that make animation their life’s work. As well as an engrossing and heartwarming tale about families of all kinds, told in remarkable detail, it’s a celebration of just what stop-motion is capable of.

The Boxtrolls is released in UK cinemas 12th September 2014, with advance screenings September 6th and 7th. Visit the film’s official UK website for more information.